- Article

- Source: Campus Sanofi

- Jul 3, 2025

Comprehensive Guide to COPD Symptoms: Dyspnea, Chronic Cough, and More

Symptoms to be considered for diagnosis of COPD

One of the most characteristic symptoms of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD) is dyspnea or shortness of breath. Dyspnea is often the first noticeable symptom and tends to progressively worsen, particularly with physical activity. Cough is another symptom of COPD and is typically a chronic, productive cough. It is often described as an ongoing cough that produces a significant amount of mucus (sputum or phlegm). These symptoms can fluctuate day to day and may manifest years before airflow obstruction develops.1

It is crucial to evaluate individuals, especially those with COPD risk factors, who present with these symptoms to identify potential underlying causes. Additionally, airflow obstruction can exist without chronic dyspnea, cough, or sputum production, and conversely, these symptoms may occur without airflow obstruction.1

Dyspnea

Shortness of breath, also known as dyspnea, is a primary indication of COPD and significantly contributes to the disease's associated disability and anxiety. Dyspnea is common at all stages of airflow obstruction, especially during exertion or physical activity. This symptom includes both a sensory experience and an effective response. Patients with COPD often characterize their dyspnea as feeling like they are exerting more effort to breathe, experiencing chest tightness, a need for air, or a sensation of suffocating. Nonetheless, the terms used to describe dyspnea can differ from one person to another and across cultures.1

Dyspnea is commonly encountered at all levels of impaired airflow and is especially noticeable during physical exertion or activity. In primary care settings, more than 40% of individuals with a COPD diagnosis report experiencing moderate to severe dyspnea.1

Dyspnea arises from multiple neurophysiological processes that disrupt or alter normal respiration. In COPD, decreased airflow and gas exchange, air trapping, and hyperinflation of the lungs lead to multiple sources of neural input that reach the somatosensory cortex and contribute to dyspnea. These inputs include afferent sensory input from respiratory muscles, feedback from chemoreceptors and irritant receptors in the lungs and airways, and increased corollary neural input from the brainstem and cortical motor centers.2

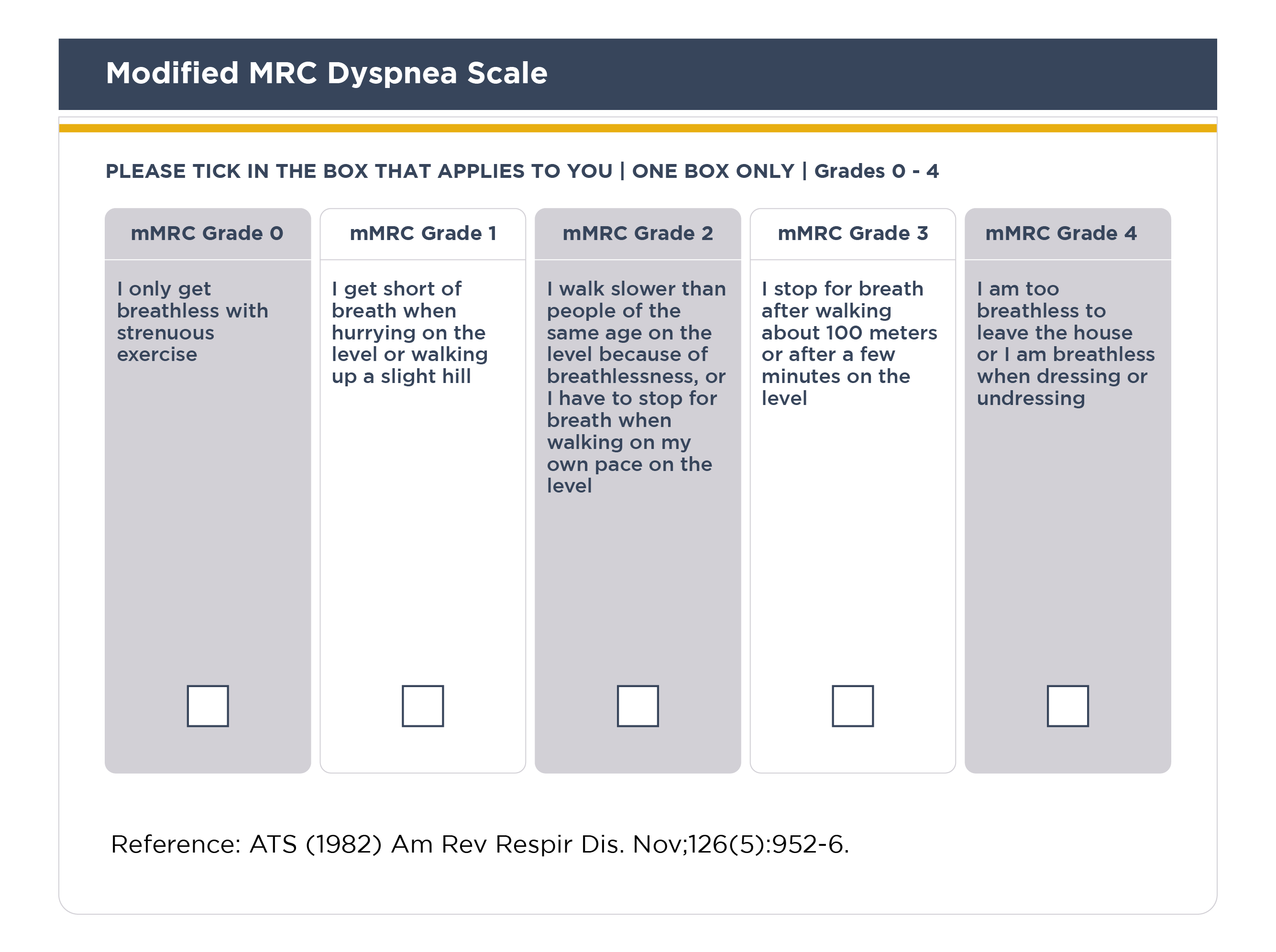

In the GOLD clinical classification system, dyspnea is assessed using the 5-level modified Medical Research Council (mMRC) scale which is the first questionnaire developed to measure breathlessness. Of note, mMRC score has a strong correlation with other comprehensive health status indicators and can forecast the risk of mortality in the future.1

Chronic cough

Chronic cough is a persistent cough that lasts 8 weeks or more in adults.3 Chronic cough is often the first symptom of COPD and may be productive (with mucus) or unproductive (dry). Patients often dismiss it as a typical result of smoking and/or exposure to environmental factors. In some cases, significant airflow obstruction may develop even without cough. In patients with severe COPD, syncope during coughing can happen due to rapid increases in intrathoracic pressure during extended coughing episodes.1

Sputum (mucus) production

Patients with COPD commonly raise small quantities of tenacious sputum with coughing. Patients who produce large volumes of sputum may have underlying bronchiectasis.1

As per GOLD report, the follow-up checklist includes changes in sputum volume and color (from least to most purulent: mucus; mucopurulent; purulent). Modulating antibiotic therapy based on the observed sputum color can be done safely without adverse effects when the sputum is white or clear. The appearance of purulent sputum indicates a rise in inflammatory mediators and can potentially signal the beginning of a bacterial exacerbation, although this correlation is relatively weak.1

Evaluating sputum production can be challenging, as patients may swallow it rather than expectorate, a behavior influenced by cultural and gender differences. Additionally, sputum production can be intermittent, with periods of flare-ups alternating with remissions.1

Wheezing and chest tightness

Inspiratory and/or expiratory wheezes, along with chest tightness, can vary in intensity both between days and within the same day. Alternatively, auscultation may reveal widespread inspiratory or expiratory wheezes.1

Chest tightness typically follows physical exertion, is often difficult to pinpoint, and is muscular in nature, potentially resulting from isometric contraction of the intercostal muscles. The absence of wheezing or chest tightness does not rule out a diagnosis of COPD, nor does the presence of these symptoms definitively indicate asthma.1

It is different from whooping cough (also known as pertussis) which is caused due to a highly contagious bacteria Bordetella pertussis. It primarily affects the respiratory system, leading to severe coughing fits that may end with a "whooping" sound when the person breathes in.4

Fatigue

Fatigue is among the most common and distressing symptoms experienced by individuals with COPD. Fatigue impacts a patient’s ability to perform daily activities and their quality of life.1

Additional symptoms

Additional clinical features such as weight loss, muscle mass loss, and anorexia are common problems in patients with severe and very severe COPD.1

- To learn more about the symptoms, read this article Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease

References

- Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease. Global strategy for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (2025 report). Accessed [May 21, 2025].. https://goldcopd.org/2025-gold-report/.

- Anzueto A and Miravitlles M. Pathophysiology of dyspnea in COPD. Postgrad Med. 2017 Apr;129(3):366-374. doi: 10.1080/00325481.2017.1301190.

- Irwin RS, French CL, Chang AB, et al. Classification of Cough as a Symptom in Adults and Management Algorithms: CHEST Guideline and Expert Panel Report. Chest. 2018;153(1): 196–209. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2017.10.016

- Whooping cough (Pertussis). Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/pertussis/about/index.html Last accessed: June 22, 2024

MAT-GLB-2400917