- Article

- Source: Campus Sanofi

- Jun 19, 2025

Etiology and risk factors for autoimmune type 1 diabetes

Etiology of autoimmune T1D

The incidence of autoimmune T1D is growing worldwide,1 making the disease an increasingly important topic for HCPs. Patients can develop comorbidities and severe complications, such as life-threatening diabetic ketoacidosis, which can significantly diminish their quality of life.1

Learn more about these impacts from real-life stories of people living with autoimmune T1D.

Autoimmune T1D manifests in children and adolescents.1,4 However, an estimated 50% of new cases emerge in adults.5 Autoimmune T1D is often misdiagnosed as type 2 diabetes, complicating estimations of incidence rates.4,5

It is a progressive autoimmune disease characterized by the destruction of insulin-producing pancreatic beta cells. Early identification can help monitor disease progression and implement preventive measures before autoimmune T1D onset.1,4,11 B cells produce autoantibodies against islet cells and activate T cells that target pancreatic cells.1,4 However, the exact causes of autoimmune T1D are not yet clearly identified.12

Learn more about the complex pathogenesis and pathophysiology of autoimmune T1D.

Risk factors of autoimmune T1D

A mix of genetic and environmental risk factors likely trigger islet autoimmunity and development of autoimmune T1D and may also vary with age of disease onset. For example, increased inflammation detected in those who develop autoimmune T1D at a younger age might be one factor contributing to the heterogeneity of the disease.13

Genetic risk factors for autoimmune type 1 diabetes

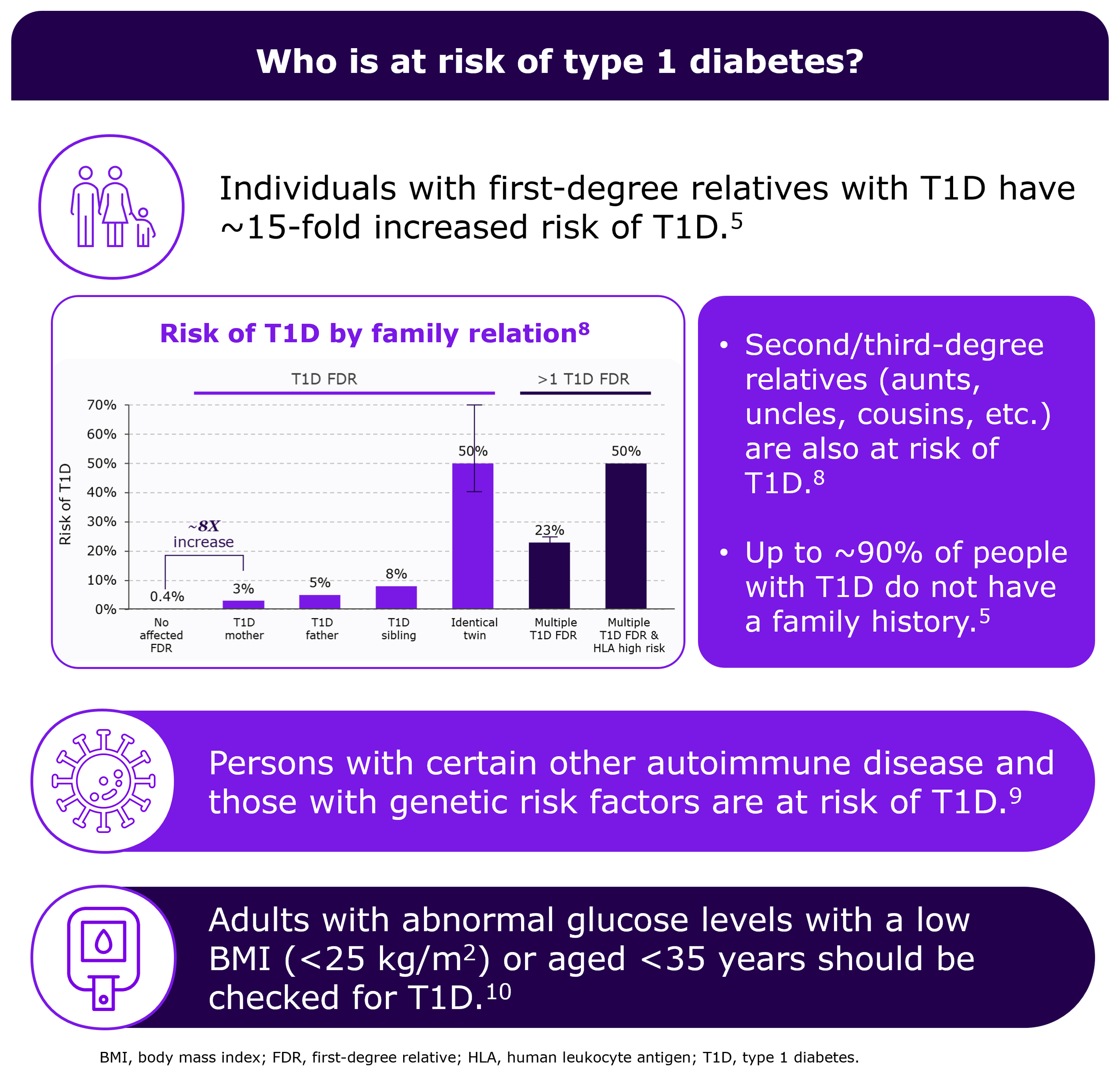

Having a relative with autoimmune T1D is a risk factor. The risk of developing autoimmune T1D is between 1 in 300 to 1 in 250.* This risk increases to 1 in 40 to 1 in 35 for those with parents who have the disease. However, the majority of patients do not have a family history of the disease.14

Shared genetic risk factors are potentially implicated both in polyautoimmunity (occurrence of ≥2 autoimmune diseases in a single patient) and family autoimmunity (presence of ≥2 autoimmune diseases in members of a nuclear family) among individuals with autoimmune T1D.15

Human leukocyte antigen (HLA) plays a role in fighting pathogens. HLA genes encoding DR and DQ are also associated with a high risk of autoimmune T1D and therefore considered genetic risk factors for autoimmune T1D.16 The genotypes are detected in 90% of pediatric autoimmune T1D patients.17 Dysregulation of other genes such as cytotoxic T cell-associated protein 4 (CTLA-4) and protein tyrosine phosphatase, nonreceptor type 22 (PTPN22) might also contribute to the onset of autoimmune T1D.18

*based on a US population

Environmental risk factors for autoimmune T1D

Some studies suggest a link between infections and autoimmune T1D.1,14 For example, recent research suggests that SARS-CoV-2 increases the risk of autoimmune T1D and accelerates the progression of the disease.12 Enteroviruses and bacterial infections have also been implicated in other studies. However, further validation is required to confirm a causal relationship.12

Other risk factors for autoimmune T1D have been proposed, including exposure to toxins and maternal diet.19,20 However, the evidence presented in these studies is often weak and/or inconclusive. 19,20

Autoimmune conditions as risk factors for autoimmune T1D

Autoimmune T1D shows a genetic overlap with several autoimmune conditions. For instance, Addison's disease is associated with a higher risk of autoimmune T1D.21 Furthermore, patients with celiac and autoimmune thyroid disease have an estimated 4-9% and 15–30% increased risk, respectively, of developing autoimmune T1D.22

There is also a familial link between autoimmune T1D and autoimmune disease.2 First-degree relatives of individuals with other autoimmune diseases including celiac and thyroid diseases may also be more likely to develop autoimmune T1D.2

Learn more about the link between autoimmune T1D and autoimmune disease.

Obesity and diet as risk factors for autoimmune T1D

Obesity and autoimmune T1D are correlated. Obesity possibly contributes to the disease by increasing insulin resistance and causing systemic inflammation.23

The intake of certain nutrients has also been associated with a higher risk for the development of autoimmune T1D. For instance, research suggests that high sugar consumption can promote the progression of autoimmune T1D.24

Other potential nutritional risk factors for autoimmune T1D, such as gluten, have also been investigated. However, the studies are inconsistent with contradictory results.14

Psychological stress as a risk factor for autoimmune T1D

There may be a link between stress and the risk of autoimmune T1D.

For instance, mothers encountering a significant life event during pregnancy may increase the risk of their child developing autoimmune T1D.25,26

Additionally, some studies suggest that children who are exposed to excessive psychological stress, such as the divorce of their parents or experience of violence, have an increased risk of autoimmune T1D.14

Modifiable factors like nutritional intake and stress may contribute to the development of autoimmune T1D, potentially providing strategies to delay or prevent onset of the disease. However, in many cases, additional robust evidence is required before evidence-based recommendations can be made.14,24

In conclusion, early identification of individuals with islet autoantibodies before the clinical onset of T1D allows for the timely implementation of preventive measures and treatments that could prevent the natural progression of autoimmune T1D and preserve beta cell function.11

Learn more about how autoimmune type 1 diabetes can be detected years before symptom onset

References

- Katsarou A, Gudbjörnsdottir S, Rawshani A, et al. Type 1 diabetes mellitus. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2017;3:17016. doi:10.1038/nrdp.2017.16.

- Cárdenas-Roldán J, Rojas-Villarraga A, Anaya JM. How do autoimmune diseases cluster in families? A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Med. 2013;11:73. doi:10.1186/1741-7015-11-73.

- Cherubini V, Chiarelli F. Autoantibody test for type 1 diabetes in children: are there reasons to implement a screening program in the general population? A statement endorsed by the Italian Society for Paediatric Endocrinology and Diabetes (SIEDP-ISPED) and the Italian Society of Paediatrics (SIP). Ital J Pediatr. 2023;49(1):87. doi:10.1186/s13052-023-01438-3.

- DiMeglio LA, Evans-Molina C, Oram RA. Type 1 diabetes. Lancet. 2018;391(10138):2449-2462. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31320-5.

- Imperatore G, Mayer-Davis EJ, Orchard TJ, Zhong VW. Prevalence and Incidence of Type 1 Diabetes Among Children and Adults in the United States and Comparison With Non-U.S. Countries. In: Cowie CC, Casagrande SS, Menke A, et al., eds. Diabetes in America. 3rd ed. Bethesda (MD): National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (US); August 2018. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK568003/. Last accessed on May 26, 2025.

- Sims EK, Besser REJ, Dayan C, et al. Screening for Type 1 Diabetes in the General Population: A Status Report and Perspective. Diabetes. 2022;71(4):610-623. doi:10.2337/dbi20-0054.

- Ziegler AG, Nepom GT. Prediction and pathogenesis in type 1 diabetes. Immunity. 2010;32(4):468-478. doi:10.1016/j.immuni.2010.03.018.

- Lebenthal Y, de Vries L, Phillip M, Lazar L. Familial type 1 diabetes mellitus - gender distribution and age at onset of diabetes distinguish between parent-offspring and sib-pair subgroups. Pediatr Diabetes. 2010;11(6):403-411. doi:10.1111/j.1399-5448.2009.00621.x.

- Mäkimattila S, Harjutsalo V, Forsblom C, Groop PH; FinnDiane Study Group. Every Fifth Individual With Type 1 Diabetes Suffers From an Additional Autoimmune Disease: A Finnish Nationwide Study. Diabetes Care. 2020;43(5):1041-1047. doi:10.2337/dc19-2429.

- American Diabetes Association Professional Practice Committee. Diagnosis and Classification of Diabetes: Standards of Care in Diabetes-2025. Diabetes Care. 2025;48(Supplement_1):S27-S49. doi:10.2337/dc25-S002.

- Al-Mulla F, Alhomaidah D, Abu-Farha M, et al. Early autoantibody screening for type 1 diabetes: a Kuwaiti perspective on the advantages of multiplexing chemiluminescent assays. Front Immunol. 2023;14:1273476. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2023.1273476.

- Debuysschere C, Nekoua MP, Alidjinou EK, Hober D. The relationship between SARS-CoV-2 infection and type 1 diabetes mellitus. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2024;20(10):588-599. doi:10.1038/s41574-024-01004-9.

- den Hollander NHM, Roep BO. From Disease and Patient Heterogeneity to Precision Medicine in Type 1 Diabetes. Front Med (Lausanne). 2022;9:932086. doi:10.3389/fmed.2022.932086.

- Stene LC, Norris JM, Rewers MJ. Risk Factors for Type 1 Diabetes. In: Lawrence JM, Casagrande SS, Herman WH, Wexler DJ, Cefalu WT, eds. Diabetes in America. Bethesda (MD): National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK); December 20, 2023. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK597412/. Last accessed on May 26, 2025.

- Głowińska-Olszewska B, Szabłowski M, Panas P, et al. Increasing Co-occurrence of Additional Autoimmune Disorders at Diabetes Type 1 Onset Among Children and Adolescents Diagnosed in Years 2010-2018-Single-Center Study. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2020;11:476. doi:10.3389/fendo.2020.00476.

- Noble JA, Valdes AM. Genetics of the HLA region in the prediction of type 1 diabetes. Curr Diab Rep. 2011;11(6):533-542. doi:10.1007/s11892-011-0223-x.

- Lucier J, Mathias PM. Type 1 Diabetes. [Updated 2024 Oct 5]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK507713/. Last accessed on May 26, 2025.

- Forgetta V, Manousaki D, Istomine R, et al. Rare Genetic Variants of Large Effect Influence Risk of Type 1 Diabetes. Diabetes. 2020;69(4):784-795. doi:10.2337/db19-0831.

- Bodin J, Stene LC, Nygaard UC. Can exposure to environmental chemicals increase the risk of diabetes type 1 development?. Biomed Res Int. 2015;2015:208947. doi:10.1155/2015/208947.

- Johansen VBI, Josefsen K, Antvorskov JC. The Impact of Dietary Factors during Pregnancy on the Development of Islet Autoimmunity and Type 1 Diabetes: A Systematic Literature Review. Nutrients. 2023;15(20):4333. doi:10.3390/nu15204333.

- Popoviciu MS, Kaka N, Sethi Y, Patel N, Chopra H, Cavalu S. Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus and Autoimmune Diseases: A Critical Review of the Association and the Application of Personalized Medicine. J Pers Med. 2023;13(3):422. doi:10.3390/jpm13030422.

- Barker JM. Clinical review: Type 1 diabetes-associated autoimmunity: natural history, genetic associations, and screening. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2006;91(4):1210-1217. doi:10.1210/jc.2005-1679.

- Oboza P, Ogarek N, Olszanecka-Glinianowicz M, Kocelak P. Can type 1 diabetes be an unexpected complication of obesity?. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2023;14:1121303. doi:10.3389/fendo.2023.1121303.

- Lamb MM, Frederiksen B, Seifert JA, Kroehl M, Rewers M, Norris JM. Sugar intake is associated with progression from islet autoimmunity to type 1 diabetes: the Diabetes Autoimmunity Study in the Young. Diabetologia. 2015;58(9):2027-2034. doi:10.1007/s00125-015-3657-x.

- Virk J, Li J, Vestergaard M, Obel C, Lu M, Olsen J. Early life disease programming during the preconception and prenatal period: making the link between stressful life events and type-1 diabetes. PLoS One. 2010;5(7):e11523. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0011523.

- Johnson SB, Lynch KF, Roth R, et al. First-appearing islet autoantibodies for type 1 diabetes in young children: maternal life events during pregnancy and the child’s genetic risk. Diabetologia. 2021;64(3):591-602. doi:10.1007/s00125-020-05344-9.

MAT-GLB-2502135-1.0-05/2025