- Article

- Source: Campus Sanofi

- Aug 26, 2024

Need to identify risk of developing autoimmune type 1 diabetes? Test for autoantibodies!

Key takeaway

Why screen for autoantibodies?

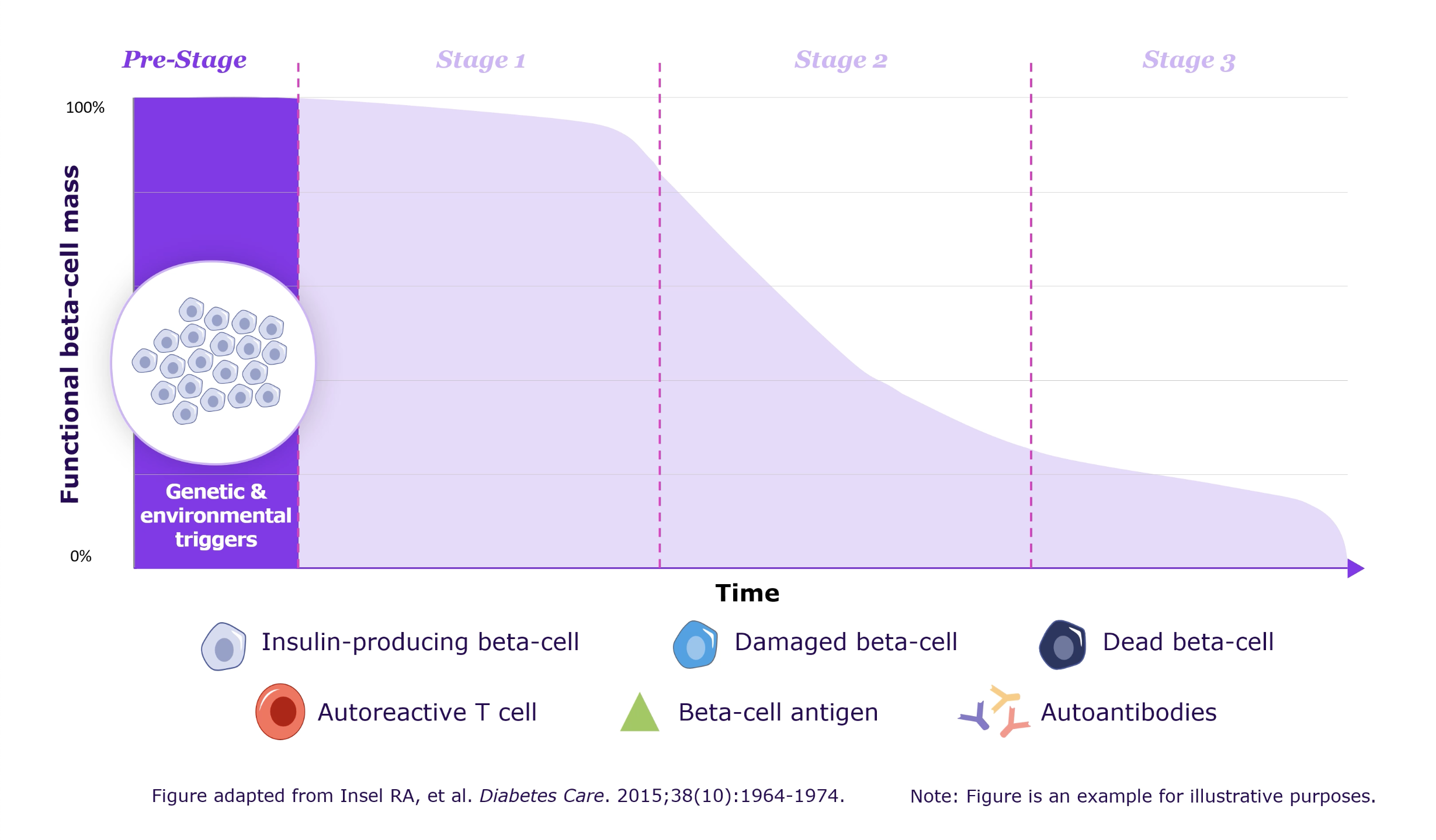

Autoimmune T1D is associated with the appearance of autoantibodies many months or years before symptom onset.1 Decline in beta-cell function occurs in three distinct stages and by the time clinical symptoms manifest, significant beta-cell loss has typically occurred.1,2 Screening for autoantibodies is important for early detection of beta-cell destruction and provides patients/caregivers with opportunity to access healthcare providers to help them prepare and develop skills for better management of T1D.2,5,6 The autoantibodies detected in autoimmune T1D include:1,2

- Glutamic acid decarboxylase antibodies (GADA)

- Insulinoma-associated-2 autoantibodies (IA-2A)

- Insulin autoantibodies (IAA)

- Zinc transporter 8 autoantibodies (ZnT8A)

Stages of autoimmune T1D depicting progressing beta-cell function decline2

How the presence of islet autoantibody determines risk of T1D?

The number of detectable autoantibodies through screening correlates with risk of developing autoimmune T1D.2,6 The majority of individuals with a single autoantibody do not progress to autoimmune T1D.7 However, presence of two or more autoantibodies increases the risk of progression to clinical T1D to 70% over 10 years and 100% over lifetime.6

Risk of progression to autoimmune T1D after seroconversion to islet autoantibody positivity6

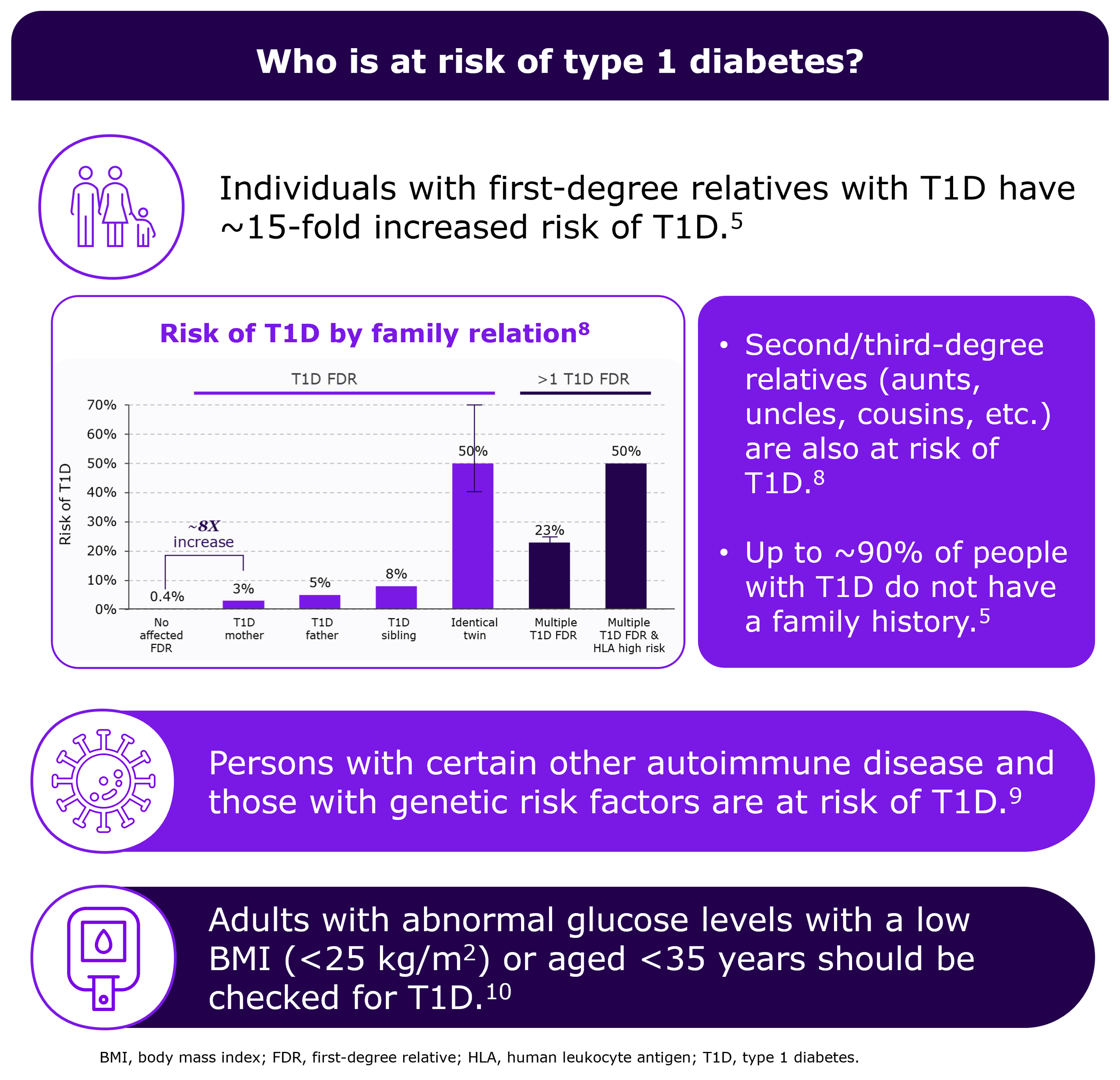

Who should be screened for islet autoantibodies?

Individuals with a family history of T1D are at greater risk of developing the disease, with up to a 15-fold increased risk if a first-degree relative has T1D.5 Additionally, individuals with certain other associated autoimmune diseases (e.g., celiac disease and autoimmune thyroiditis) and adults with abnormal glucose levels with a low BMI (<25 kg/m2) or aged <35 years are also likely to develop T1D.9,10.

Explore the connection between autoimmune T1D and other associated autoimmune conditions

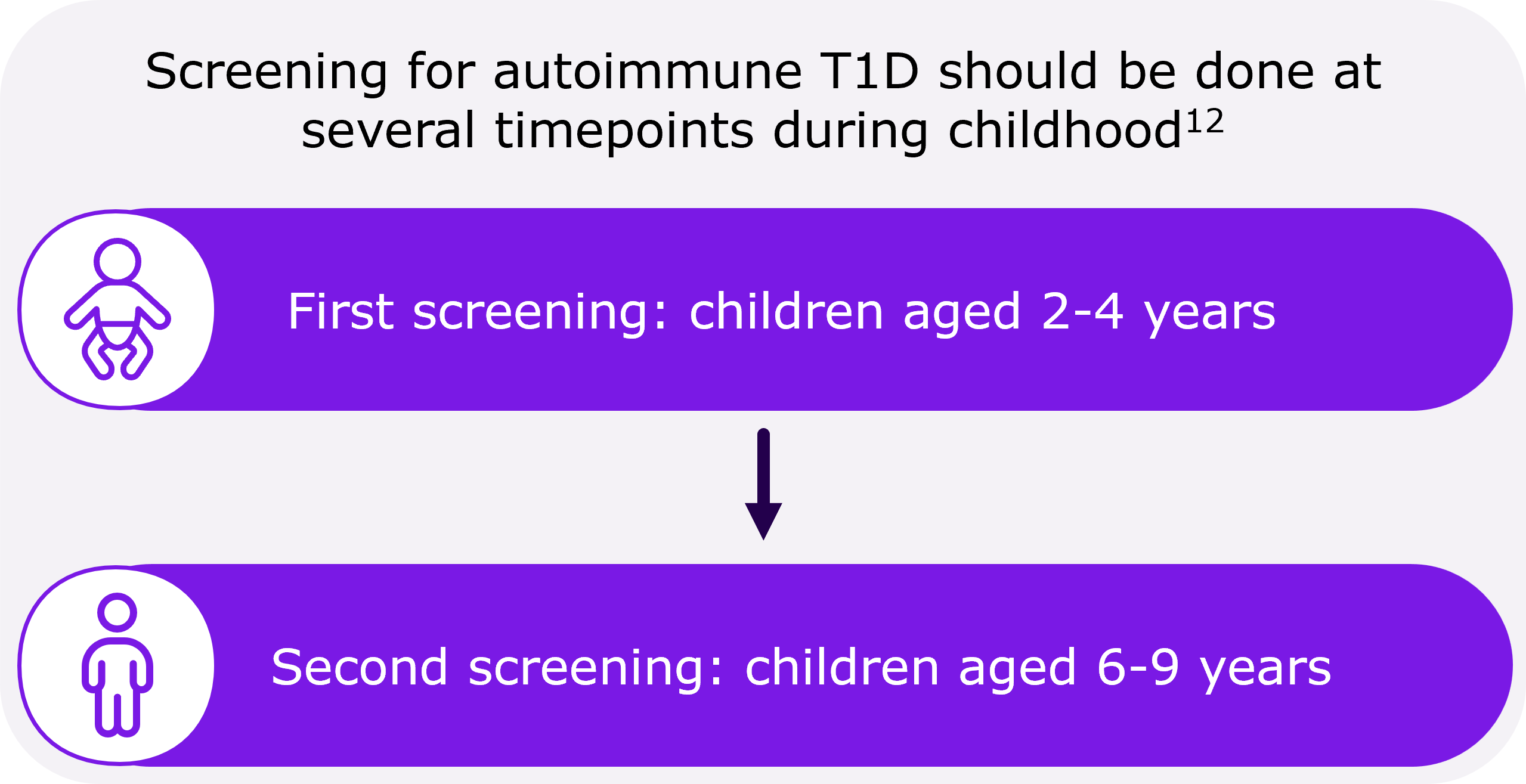

What is right age for screening for autoimmune T1D?

Although T1D can manifest at any age, it most commonly occurs in children, teenagers, or young adults.1,11 Autoantibodies often emerge before the age of 6, even in cases where T1D is diagnosed much later in childhood. Screening for islet autoantibodies at ages of 2 and 6 has proven to be sensitive and efficient in predicting autoimmune T1D.12

What are the benefits of screening for autoimmune T1D?

Screening shows that approximately 95% of relatives of individuals with T1D test negative for autoantibodies, which can provide reassurance, especially to families with an affected member.5

In individual who test positive for autoantibodies, screening leads to early detection of autoimmune T1D, which in turn: 6

- Can prevent diabetes ketoacidosis, a life-threatening complication of diabetes.

- Provide preparation time to patients and caregivers to develop skills to manage T1D.

- Enable access to medical care to provide ongoing education and monitoring.

Know more about the monitoring of people screened positive for ≥1 islet autoantibodies

Widespread screening for autoimmune T1D is critical for early identification of at-risk individuals, thereby reducing the complications at diagnosis and guiding targeted interventions to manage and potentially dealy disease progression.13

References

- Katsarou A, Gudbjörnsdottir S, Rawshani A, et al. Type 1 diabetes mellitus. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2017;3:17016.

- Insel RA, Dunne JL, Atkinson MA, et al. Staging presymptomatic type 1 diabetes: A scientific statement of JDRF, the Endocrine Society, and the American Diabetes Association. Diabetes Care. 2015;38(10):1964-1974.

- Tiberti C, Yu L, Lucantoni F, et al. Detection of four diabetes specific autoantibodies in a single radioimmunoassay: an innovative high-throughput approach for autoimmune diabetes screening. Clin Exp Immunol. 2011;166(3):317-324.

- Cortez FJ and Gebhart D, Robinson PV, et al. Sensitive detection of multiple islet autoantibodies I type 1 diabetes using small sample volumes by agglutination-PCR. PLoS One. 2020;15(11):e0242049.

- Sims EK, Besser REJ, Dayan C, et al; NIDDK Type 1 Diabetes TrialNet Study Group. Screening for type 1 diabetes in the general population: A status report and perspective. Diabetes. 2022;71(4):610-623.

- Simmons KM and Sims EK. Screening and prevention of type 1 diabetes: Where are we? J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2023;108(12):3067-3079.

- DiMeglio LA, Evans-Molina C and Oram RA. Type 1 diabetes. Lancet. 2018;391(10138):2449–2462.

- Ziegler AG and Nepom GT. Prediction and pathogenesis in type 1 diabetes. Immunity. 2010;32(4):468-78.

- Makimattila S, Harjutsalo V, Forsblom C, et al. Every fifth individual with type 1 diabetes suffers from an additional autoimmune disease: a Finnish nationwide study. Diabetes Care. 2020;43(5):1041-1047.

- American Diabetes Association. Standards of care in diabetes—2024. Diabetes Care. 2024;47(suppl 1):S1-S321.

- You W-P and Henneberg M. Type 1 diabetes prevalence increasing globally and regionally: The role of natural selection and life expectancy at birth. BMJ Open Diabetes Research and Care. 2016;4:e000161.

- Ghalwash M, Dunne JL, Lundgren M, et al. Two-age islet-autoantibody screening for childhood type 1 diabetes: a prospective cohort study. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2022;10(8):589-596.

- Greenbaum CJ. A Key to T1D Prevention: Screening and monitoring relatives as part of clinical care. Diabetes. 2021;70:1029–1037.

MAT-GLB-2404542-v1.0-07/2024