- Article

- Source: Campus Sanofi

- Aug 26, 2024

Early detection of autoimmune type 1 diabetes could reduce the risk of diabetic ketoacidosis

Key takeaway

Can screening for T1D autoantibodies help prevent DKA?

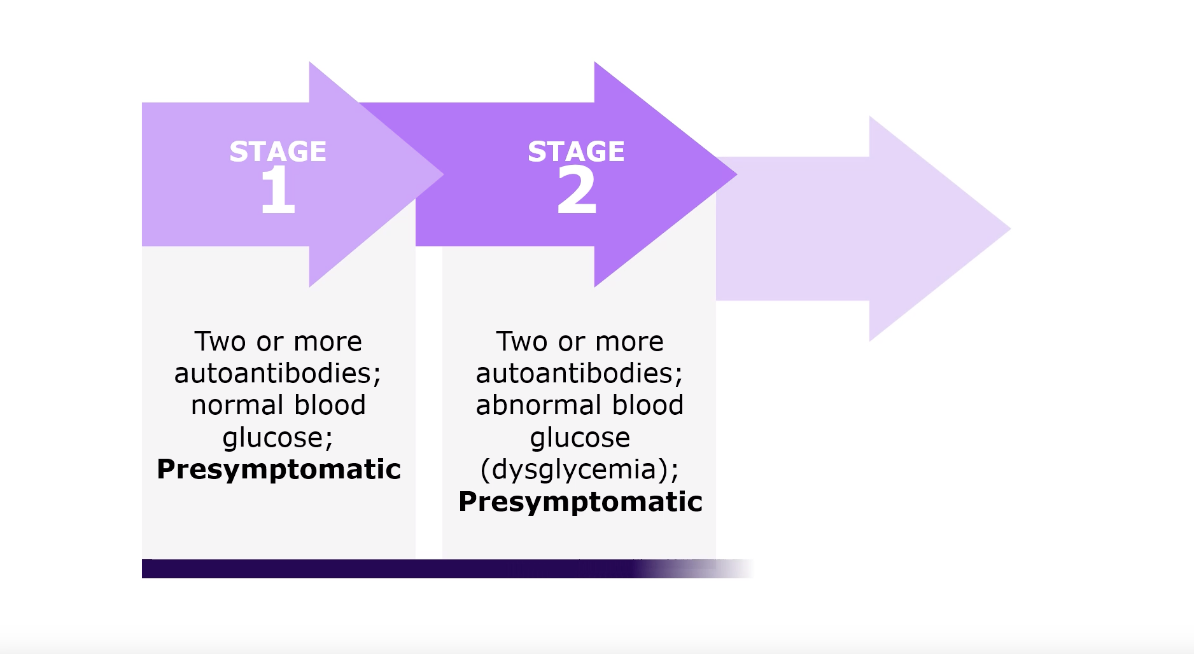

Anti-islet autoantibodies, responsible for destruction of insulin-producing beta-cells, can be detected during the presymptomatic phase (Stage 1 and 2) of autoimmune T1D. If left undetected, there is progression from the presymptomatic phase to symptomatic phase (Stage 3), which is characterized by beta-cell functional loss and hyperglycemia, which may often lead to ketoacidosis.6

Stages of autoimmune type 1 diabetes6

Know more about different stages of autoimmune T1D

Click here to know more about different stages of autoimmune T1D.

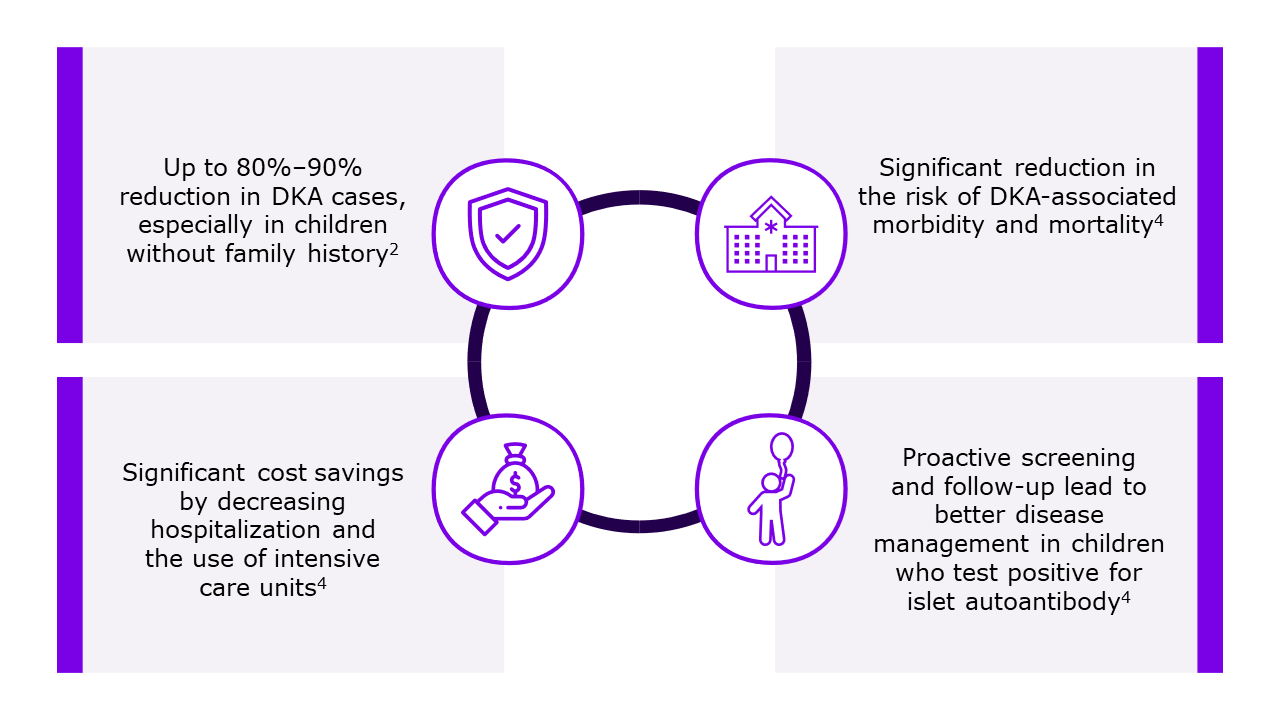

Screening for beta-cell autoantibodies in high-risk individuals allows for early diagnosis of T1D, timely intervention through monitoring and treatment, and prevention of complications such as DKA.1,6 Moreover, preventing DKA through screening results in reduced DKA-associated morbidity, mortality, and healthcare cost.4

Benefits of early T1D screening2,4

Is DKA a critical risk for children with T1D?

Diabetic ketoacidosis is a critical complication and the leading cause of hospitalization in children with autoimmune T1D. It accounts for 70% of diabetes-related deaths in those under 10 years, often due to cerebral edema.5,7

Type 1 diabetes is often diagnosed following a DKA event. The incidence of DKA at the onset of T1D varies worldwide, ranging from 15% to 80%.8 Diabetic ketoacidosis at the diagnosis of autoimmune T1D significantly worsens glycemic control by potentially accelerating beta-cell loss. Additionally, children who experience DKA may face long-term cognitive complications, impairing their ability to engage in self-care.2

Who is at risk of DKA?

Diabetic ketoacidosis predominantly affects people with T1D but can also occur in those with type 2 diabetes. Common triggers in both populations include catabolic stress from:9

- Acute illnesses and injuries

- Surgery

- Infections

- Non-compliance with treatment

- New-onset diabetes

- Other acute medical conditions

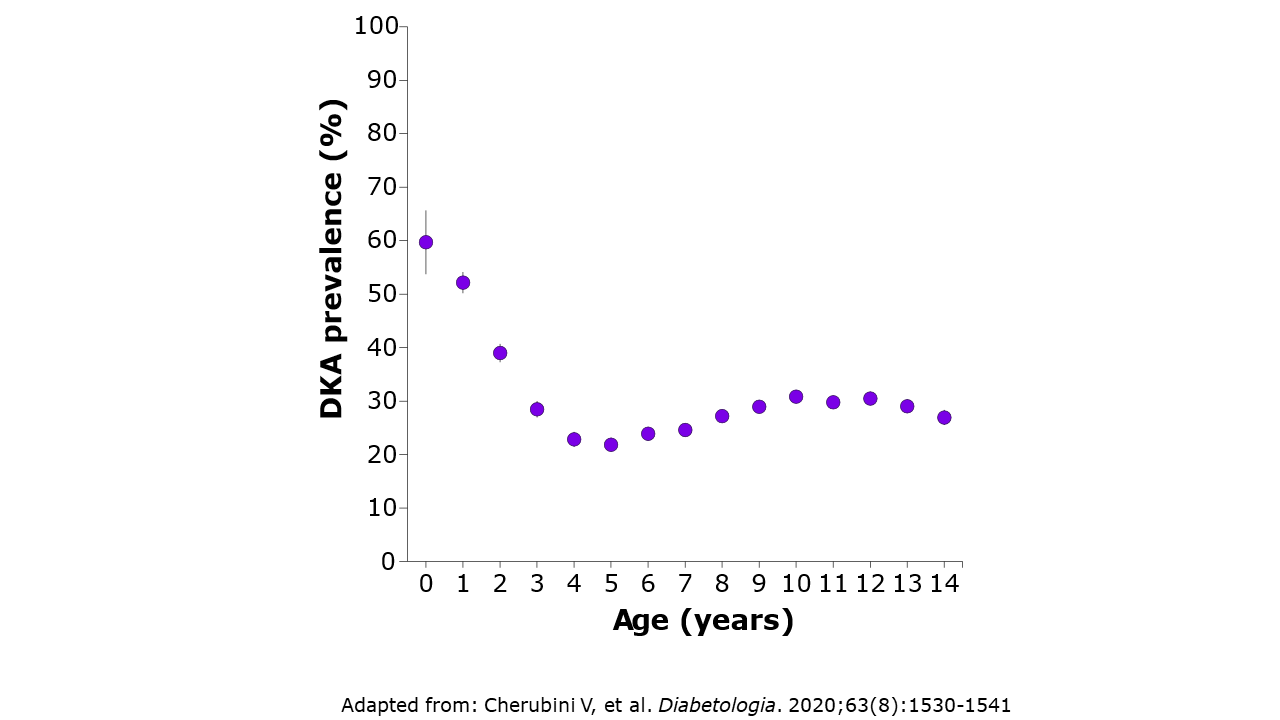

The risk of DKA is notably higher among younger children with T1D.1 It is concerning that T1D diagnosis in children under 5 years often coincides with DKA. The reported prevalence of DKA in this age group at diagnosis ranges from 17.3% to 54.5%.4 Recognizing signs and symptoms in these children can be particularly challenging, potentially leading to delayed diagnosis.1

Risk of DKA by age1

Children of siblings of individuals with T1D show the lowest rate of DKA, highlighting the importance of parental awareness regarding diabetes signs and symptoms.2

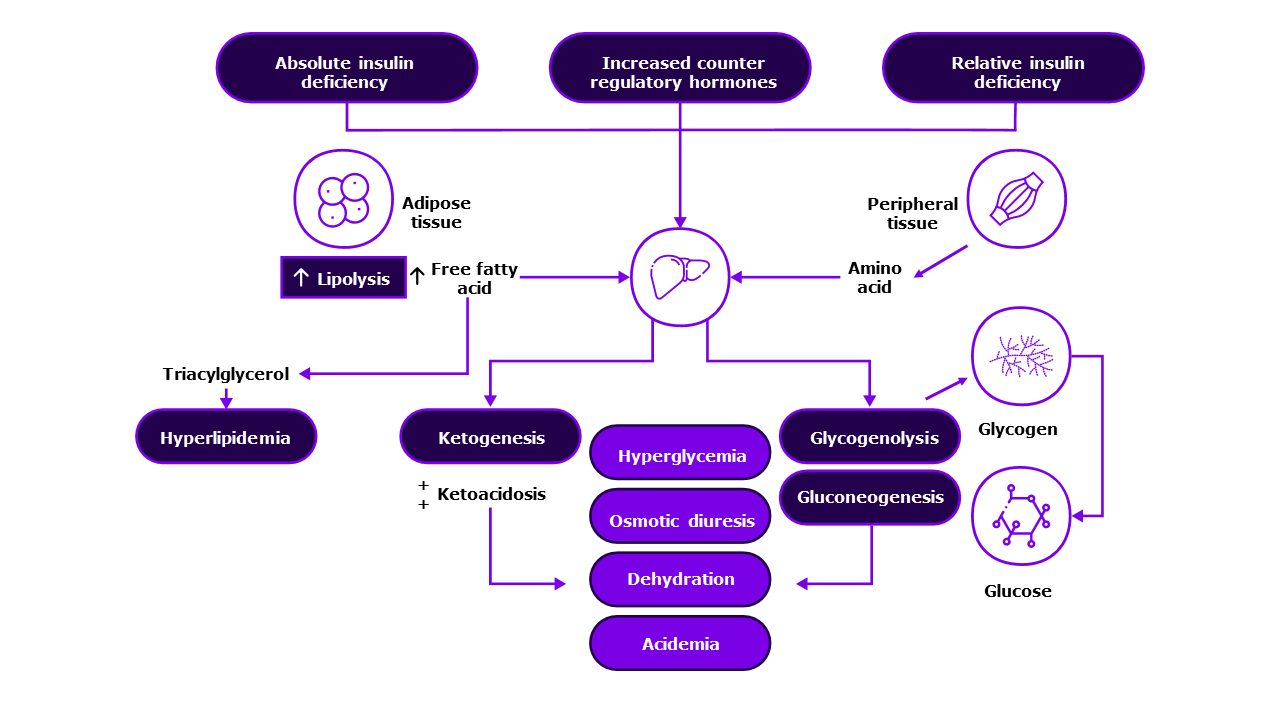

What is the pathogenesis of DKA?

Autoimmune T1D, resulting from the destruction of pancreatic beta-cells, causes insulin deficiency. Insulin deficiency, coupled with increased counterregulatory hormones, triggers the release of free fatty acids from adipose tissue. These fatty acids are then oxidized in the liver to form ketone bodies, leading to ketoacidosis. This ultimately causes worsening of hyperglycemia, as illustrated in the below figure.5,9

Pathogenesis of DKA10

How is DKA evaluated?

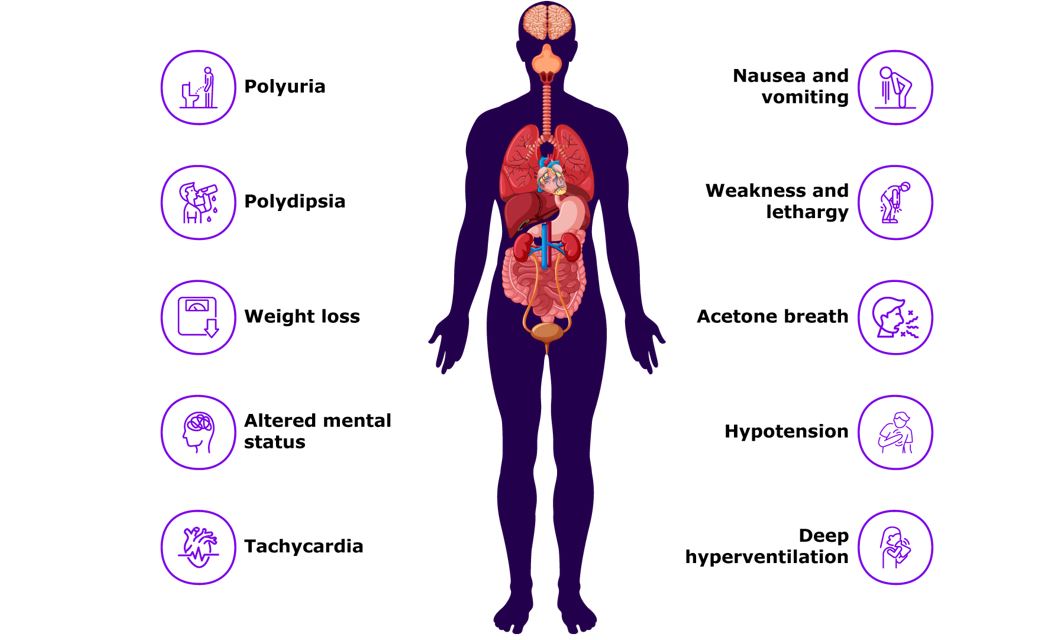

Diabetic ketoacidosis can be evaluated through both clinical signs and laboratory tests. Clinically, DKA manifests with symptoms such as polyuria, polydipsia, hyperglycemia, weight loss and acetone breath.11

Symptoms of DKA11

In addition to clinical signs, DKA is characterized by specific laboratory findings, with the presence of:5

- Hyperglycemia (blood glucose >200 mg/dL),

- Metabolic acidosis (venous pH <7.3 or serum bicarbonate concentration

<15 mEq/L), and - Ketonemia or moderate/high ketonuria

The severity of DKA is primarily determined by the degree of acidosis observed in these laboratory parameters, as depicted in below table.5

Diabetic ketoacidosis severity classification5

|

Mild | Moderate | Severe | |

| Serum pH | 7.2-7.3 | 7.0-7.2 | <7.0 |

|

Serum HCO3 (mEq/L) | 15–18 | 10–15 | <10 |

HCO3, bicarbonate

DKA is a life-threatening condition often associated with high mortality, morbidity, and healthcare expenditure. Early screening and detection of T1D are crucial for preventing DKA1,5

References

- Cherubini V, Grimsmann JM, Åkesson K, et al. Temporal trends in diabetic ketoacidosis at diagnosis of paediatric type 1 diabetes between 2006 and 2016: results from 13 countries in three continents. Diabetologia. 2020;63(8):1530-1541.

- Duca LM, Wang B, Rewers M, and Rewers A. Diabetic ketoacidosis at diagnosis of type 1 diabetes predicts poor long-term glycemic control. Diabetes Care. 2017;40(9):1249-1255.

- Nakhla M, Cuthbertson D, Becker DJ, et al. Diabetic ketoacidosis at the time of diagnosis of type 1 diabetes in children: insights from TRIGR. JAMA. 2021;175(5):518-520.

- Elding Larsson H, Vehik K, et al. TEDDY Study Group; SEARCH Study Group; Swediabkids Study Group; DPV Study Group; Finnish Diabetes Registry Study Group. Reduced prevalence of diabetic ketoacidosis at diagnosis of type 1 diabetes in young children participating in longitudinal follow-up. Diabetes Care. 2011;34(11):2347-2353.

- Bonadio W. The evaluation and management of pediatric diabetic ketoacidosis: A comprehensive review. Clinical Pediatrics. 2024; 62 (6):551-564.

- Sims EK, Besser REJ, Dayan C, et al; NIDDK type 1 diabetes TrialNet study group. Screening for type 1 diabetes in the general population: A status report and perspective. Diabetes. 2022;71(4):610-623.

- Wolfsdorf J, Craig ME, Daneman D, et al. Diabetic ketoacidosis. Pediatric Diabetes. 2007;8(1):28-42.

- Simmons KM and Sims EK. Screening and prevention of type 1 diabetes: Where are we? J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2023;108(12):3067-3079.

- Lizzo JM, Goyal A, and Gupta V. Adult diabetic ketoacidosis. [Updated 2023 Jul 10]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK560723/. Accessed on 10 Jul 2024.

- Algarni A. Treatment considerations and pharmacist collaborative care in diabetic ketoacidosis management. J Pharmacol Pharmacother. 2022;13(3):215–221.

- Lee CS and Rickard J. Review of diabetic ketoacidosis management. USPharm. 2018;43(11):26-28.

MAT-GLB-2404923-v2.0-10/2024