- Article

- Source: Campus Sanofi

- Dec 1, 2025

Early identification of autoimmune type 1 diabetes can reduce its psychological impact.

Key takeaway

Can autoimmune T1D predispose patients to psychological issues?

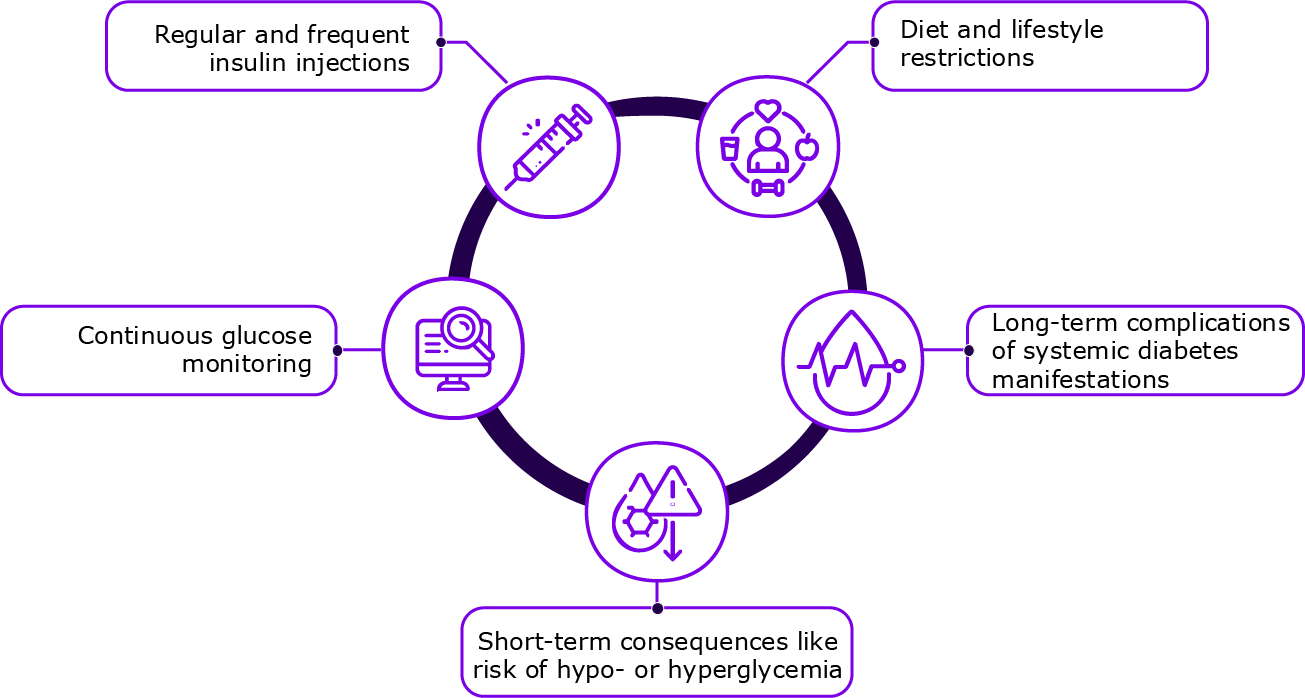

Symptomatic autoimmune T1D requires life-long insulin therapy.3 Insulin regimens in T1D are often intensive, comprising multiple daily injections or insulin pump therapy.4

Self-management by the patient forms the basis of diabetes care, which can be psychologically demanding. Besides the insulin administration, living with T1D involves constant blood glucose monitoring, dietary and lifestyle restrictions, and consideration of physical activity levels. These daily self-management tasks, along with worries for the future, can lead to psychological and behavioral reactions in patients.3,5

Factors causing psychological and behavioral reactions in patients with T1D5

What are the common psychological issues in patients with T1D?

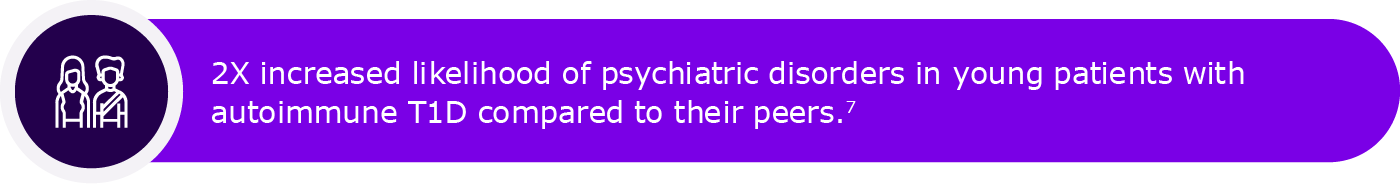

A patient self-reported international survey revealed that patients with diabetes experience various forms of emotional distress as part of the psychosocial burden of living with the condition.6 The most common issues reported were anxiety, depression, fear of low blood sugars, low mood, and diabetes-related distress.6

Among patients with T1D, the prevalence of diabetes distress ranges from 22% to 42%, with a nine-month incidence as high as 54%.1 The distress is also associated with a reduced health-related quality of life.1 Sleep disturbances are also prevalent, with 30% to 50% of patients with T1D experiencing poor sleep, and over 50% meeting criteria for moderate to severe obstructive sleep apnea.1 Other common mental health disorders associated with autoimmune T1D include eating, personality and behavioral disorders.8,9

Psychological disorders in autoimmune T1D6,8,9

How can psychological issues impact diabetes self-management?

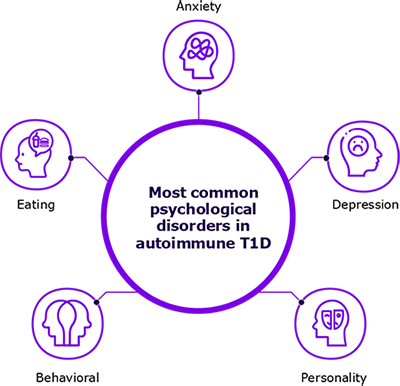

Psychosocial issues impact glycemic outcomes by increasing HbA1c, and may also result in increased blood pressure, cholesterol levels, microvascular, and macrovascular complications in patients with T1D. Additionally, they can lead to reduced self-care behaviors, comorbid psychosocial issues, decreased quality of life and increased mortality.1

Anxiety and depression can negatively impact T1D management. Anxiety may cause emotional distress, fear of hypoglycemia, and less frequent glucose monitoring by negatively impacting adherence to therapy, which in turn can affect glycemic control. Depressive symptoms can also negatively impact glycemic control by reducing motivation to adhere with prescribed therapies and perform regular glucose monitoring.4

What can be the psychological impact of T1D in families and caregivers?

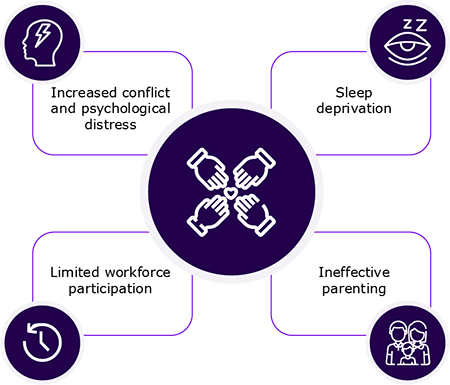

The psychological impact of T1D can sometimes be greater on family members than on patients.10 Parents of children with T1D face overwhelming challenges, including constant worry about hypoglycemia or hyperglycemia, and responsibility for their child’s health.11

Psychological impact of T1D on family and caregivers11,12

Parents, especially mothers, of children with newly diagnosed T1D are at a higher risk of being diagnosed with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).13 Higher parental depression and anxiety are linked to decreased monitoring, lower self-efficacy, and challenges in learning diabetes management, contributing to suboptimal T1D care.11

What are the psychological concerns with a late-stage T1D diagnosis?

T1D is a continuum and can be identified at the presymptomatic stage.16

Learn how autoimmune T1D can be detected years before symptom onset.

A delay in the diagnosis of autoimmune T1D increases the risk of DKA at diagnosis, a severe and potentially life-threatening complication, which can result in persistent challenges in glycemic control and recurrent episodes of DKA.2,17,18

Patients experiencing recurrent episodes of DKA exhibit higher levels of anxiety, depression, and diabetes distress, along with increased challenges in emotion regulation and personality dysfunction.19,20 A case-controlled study found that over 60% of these patients had a diagnosed mental health disorder.19

The psychological impact of DKA extends beyond immediate health concerns. It is also associated with suicidal or self-injurious behaviors, with one study reporting an 11-times higher suicide rate in patients with T1D compared with that in the general population.21 In children, DKA has been linked to poorer neurodevelopmental outcomes, including lower IQ.21

Learn how early detection of autoimmune T1D could reduce the risk of diabetic ketoacidosis.

Can screening results have a psychosocial impact on patients and their families?

Patients who screen positive for T1D-related autoantibodies and their families may experience significant stress along with a myriad of emotional and behavioral reactions in response to this life-altering news.22 Despite these challenges, early screening results in better long-term outcomes.23

Thus, psychosocial support should be provided to both patients and their families with the aim of supporting them in successfully managing the psychosocial impact.22

Learn more about screening for autoantibodies to identify individuals at risk for autoimmune T1D.

Consensus guidance recommendations for psychosocial support for patients identified at risk or at early stage T1D

The consensus document for monitoring individuals with single (at-risk) and multiple (early-stage T1D) islet autoantibody positivity provides the following expert clinical advice for psychosocial support:22

- Emotional, cognitive and behavioral functioning should be assessed in people at risk or with early-stage T1D and their family members, when appropriate with a specific focus on anxiety, risk perception and behavior changes

- HCPs should initiate psychosocial support to individual at risk or with early-stage T1D and/or their caregivers and family members by inquiring about reactions to the autoantibody diagnosis, using guiding questions and standardized and validated questionnaires

- At each monitoring visit, there should be enquiries into current needs, particularly coping

- Psychological care should be integrated into routine medical visits and, whenever possible, delivered by providers with diabetes-specific training

Learn how should individuals with positive autoimmune T1D autoantibodies be monitored over time.

What is the importance of psychosocial support in patients with T1D?

Addressing the emotional and mental health challenges of T1D is crucial for improving overall outcomes.24 However, the current clinical care falls short of adequately addressing the psychosocial needs of those living with the condition. The lack of attention to psychosocial issues creates a barrier to achieving optimal diabetes self-management.6 However, a comprehensive psychological support in autoimmune T1D can significantly improve both mental and physical health outcomes.4,25

References

- American Diabetes Association (ADA) Professional Practice Committee; 5. Facilitating positive health behaviors and well-being to improve health outcomes: Standards of care in diabetes—2024. Diabetes Care. 2024; 47 (Supplement_1): S77–S110. doi.org/10.2337/dc24-S005.

- Cherubini V, Grimsmann JM, Åkesson K, et al. Temporal trends in diabetic ketoacidosis at diagnosis of paediatric type 1 diabetes between 2006 and 2016: Results from 13 countries in three continents. Diabetologia. 2020;63(8):1530–1541. doi:10.1007/s00125-020-05152-1

- Benton M, Cleal B, Prina M, et al. Prevalence of mental disorders in people living with type 1 diabetes: A systematic literature review and meta-analysis. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2023;80:1–16. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2022.11.004.

- Bombaci B, Torre A, Longo A, et al. Psychological and clinical challenges in the management of type 1 diabetes during adolescence: A narrative review. Children (Basel). 2024;11(9):1085. doi: 10.3390/children11091085.

- Formánek T, Chen D, Šumník Z, et al. Childhood-onset type 1 diabetes and subsequent adult psychiatric disorders: A nationwide cohort and genome-wide Mendelian randomization study. Nat Ment Health. 2024;2(9):1062–1070. doi:10.1038/s44220-024-00280-8.

- Kelly RC, Holt RIG, Desborough L, et al. The psychosocial burdens of living with diabetes. Diabet Med. 2024;41(3):e15219. doi: 10.1111/dme.15219.

- van Duinkerken E, Snoek FJ, de Wit M. The cognitive and psychological effects of living with type 1 diabetes: A narrative review. Diabet Med. 2020;37(4):555–563. doi:10.1111/dme.14216.

- Cooper MN, Lin A, Alvares GA, de Klerk NH, Jones TW, Davis EA. Psychiatric disorders during early adulthood in those with childhood onset type 1 diabetes: Rates and clinical risk factors from population-based follow-up. Pediatr Diabetes. 2017;18(7):599–606. doi:10.1111/pedi.12469.

- Lunkenheimer F, Eckert AJ, Hilgard D, et al. Posttraumatic stress disorder and diabetes-related outcomes in patients with type 1 diabetes. Sci Rep. 2023;13(1):1556. doi: 10.1038/s41598-023-28373-x.

- Allen V, Mahieu A, Kasireddy E, et al. Humanistic burden of pediatric type 1 diabetes on children and informal caregivers: Systematic literature reviews. Diabetol Metab Syndr. 2024;16(1):73. doi: 10.1186/s13098-024-01310-2.

- Whittemore R, Jaser S, Chao A, Jang M, Grey M. Psychological experience of parents of children with type 1 diabetes: A systematic mixed-studies review. Diabetes Educ. 2012;38(4):562–579. doi:10.1177/0145721712445216.

- Pons Perez S, Robinson H, Brophy C, Warner JT. Impact of a new diagnosis of childhood type 1 diabetes on parents’ sleep and employment. Oral presentation 21. Presented at: The International Society for Pediatric and Adolescent Diabetes (ISPAD) 2024 Annual Conference; October 17, 2024; Lisbon, Portugal.

- Rechenberg K, Grey M, Sadler L. Stress and posttraumatic stress in mothers of children with type 1 diabetes. J Fam Nurs. 2017;23(2):201–225. doi:10.1177/1074840716687543.

- De Sousa B, Nogueira Machado S, Delgado L, Meireles C, Dias Â. Parental burnout associated with type 1 diabetes - preliminary results. Poster 125. Presented at: The International Society for Pediatric and Adolescent Diabetes (ISPAD) 2024 Annual Conference; October 17, 2024; Lisbon, Portugal.

- Kingsley O, Bebbington K, Naragon-Gainey K. Understanding the impacts of parental anxiety in the context of caring for a young child with type 1 diabetes: a qualitative study. Poster 205. Presented at: The International Society for Pediatric and Adolescent Diabetes (ISPAD) 2024 Annual Conference; October 18, 2024; Lisbon, Portugal.

- Insel RA, Dunne JL, Atkinson MA, et al. Staging presymptomatic type 1 diabetes: A scientific statement of JDRF, the Endocrine Society, and the American Diabetes Association. Diabetes Care. 2015;38(10):1964–1974. doi:10.2337/dc15-1419.

- Edelman S, Holyoke K, Symowicz J, Rinehart L, Gordon S. Preventing and managing diabetic ketoacidosis in people with T1D. https://www.breakthrought1d.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/JDRF_Ebrief-5_DKA.pdf.

- Sims EK, Besser REJ, Dayan C, et al. Screening for type 1 diabetes in the general population: A status report and perspective. Diabetes. 2022;71(4):610–623. doi:10.2337/dbi20-0054

- Hamblin PS, Abdul-Wahab AL, Xu SFB, Steele CE, Vogrin S. Diabetic ketoacidosis: A canary in the mine for mental health disorders?. Intern Med J. 2022;52(6):1002–1008. doi:10.1111/imj.15214

- Garrett CJ, Moulton CD, Choudhary P, Amiel SA, Fonagy P, Ismail K. The psychopathology of recurrent diabetic ketoacidosis: A case-control study. Diabet Med. 2021;38(7):e14505. doi: 10.1111/dme.14505.

- Al Alshaikh L, Doherty AM. The relationship between diabetic ketoacidosis and suicidal or self-injurious behaviour: A systematic review. J Clin Transl Endocrinol. 2023;34:100325. doi: 10.1016/j.jcte.2023.100325.

- Phillip M, Achenbach P, Addala A, et al. Consensus guidance for monitoring individuals with islet autoantibody-positive pre-stage 3 type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2024;47(8):1276–1298. doi:10.2337/dci24-0042.

- Elding Larsson H, Vehik K, Bell R, et al. Reduced prevalence of diabetic ketoacidosis at diagnosis of type 1 diabetes in young children participating in longitudinal follow-up. Diabetes Care. 2011;34(11):2347–52. doi: 10.2337/dc11-1026.

- Kalra S, Jena BN, Yeravdekar R. Emotional and psychological needs of people with diabetes. Indian J Endocrinol Metab. 2018;22(5):696–704. doi:10.4103/ijem.IJEM_579_17.

- Małachowska M, Gosławska Z, Rusak E, Jarosz-Chobot P. The role and need for psychological support in the treatment of adolescents and young people suffering from type 1 diabetes. Front Psychol. 2023;13:945042. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.945042.

MAT-GLB-2503432-2.0 - 12/2025