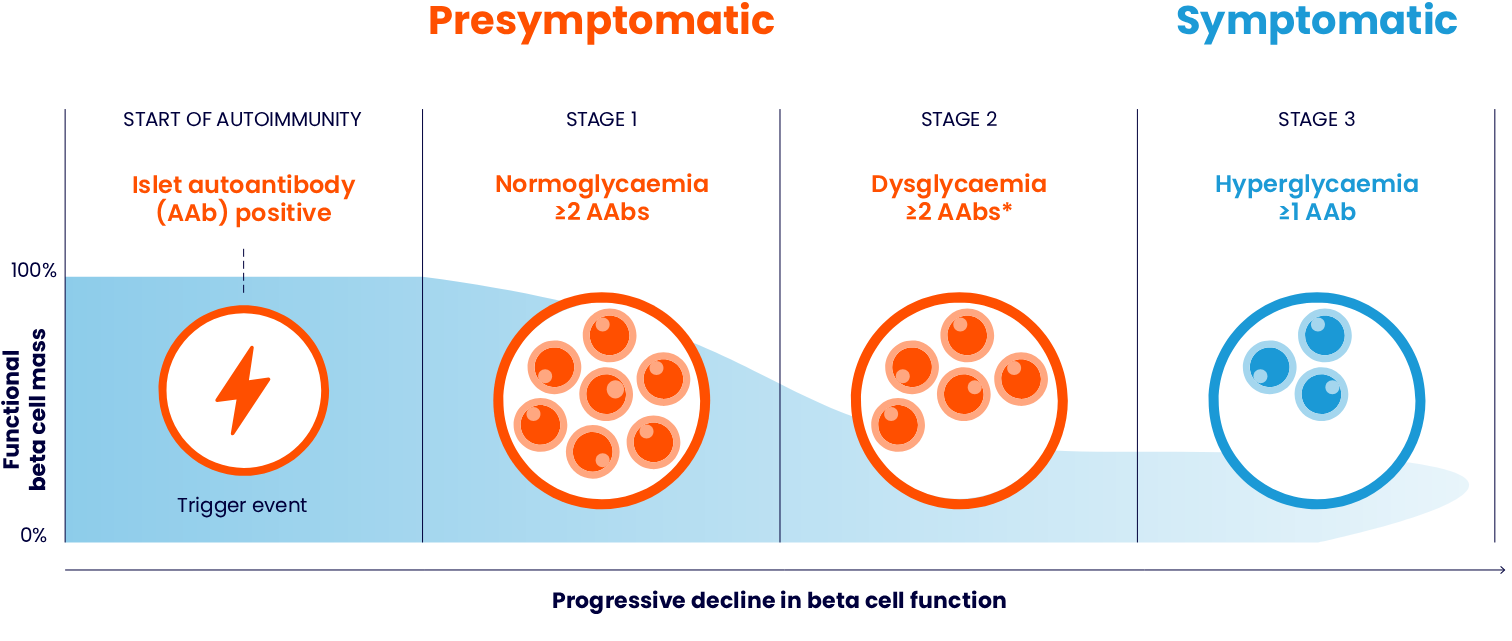

People with autoimmune T1D progress through three clinically distinct stages as their beta cells are destroyed1,3,4

| Blood test | Stage 1 Normoglycaemia | Stage 2 Dysglycaemia | Stage 3 Hyperglycaemia |

| Fasting Plasma Glucose (FPG) | <5.6 mmol/L | 5.6–6.9 mmol/L | ≥7.0 mmol/L |

| 120-min oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) | <7.8 mmol/L | 7.8–11.0 mmol/L | ≥11.1 mmol/L |

| Glycated haemoglobin (HbA1c) | <39 mmol/mol (<5.7%) | 39–47 mmol/mol (5.7–6.4%) | ≥48 mmol/mol (≥6.5%) |

Sims EK, et al. 2022 and Phillip M, et al. 2024.3,4

Pathogenesis of autoimmune T1D

The pathogenesis of autoimmune T1D involves a complex interaction between the beta cells and immune system.5 It begins when the autoreactive T cells recognise and destroy the pancreatic beta cells. This leads to a critical decline in insulin levels, which in turn causes ineffective control of blood glucose levels. Eventually, the remaining beta cells become insufficient to maintain normal blood glucose reducing insulin secretion and leading to autoimmune T1D.6

Autoimmune T1D is a progressive condition; the decline of beta cell function can begin months to years before symptoms appear1,5

Generally, autoimmune T1D follows a continuous progression through distinct stages before clinical symptoms emerge. The rate at which the disease advances from the initial autoimmune response to symptomatic T1D varies among individuals, ranging from a few months to decades.1

While peak age of autoimmune T1D diagnosis occurs in adolescence, it can strike at any time8,9

Globally and historically, autoimmune T1D has a peak incidence in adolescence; however, the majority of people diagnosed each year are adults10

Adapted from Gregory GA, et al. 2022.10

Autoimmune T1D may be identified before symptom onset1

Conventionally, autoimmune T1D is diagnosed after onset of clinical symptoms. However, latest research evidence on pathophysiological mechanisms leading to development and progression of T1D enable us to identify autoimmune T1D in its presymptomatic stages (Stages 1 and 2).1

Autoimmune T1D can be detected early, allowing for the identification of at-risk individuals months to years before clinical symptoms develop1,5

Get in Touch with Us

Questions? Leave your details and we'll reach out to you at your preferred time.

Get in touchINDICATION: TZIELD is indicated to delay the onset of Stage 3 T1D in adult and paediatric patients 8 years of age and older with Stage 2 T1D.11

*Reversion to single AAb or negative status can occur in some people with previously confirmed multiple AAb positivity.3

†In a pooled analysis of three prospective cohort studies including children from Colorado, Finland, and Germany, progression to autoimmune T1D at 10-year follow-up after AAb seroconversion in 585 children with multiple AAbs was 69.7% (95% confidence interval [CI], 65.1%–74.3%).7

AAb, autoantibody; CI, confidence interval; FPG, fasting plasma glucose; HbA1c, glycated haemoglobin; OGTT, oral glucose tolerance test; T1D, Type 1 diabetes.

- Insel RA, et al. Diabetes Care. 2015; 38(10): 1964–1974.

- Pugliese A. Pediatr Diabetes. 2016; 17(Suppl. 22): 31–36.

- Phillip M, et al. Diabetes Care. 2024; 47(8): 1276–1298.

- Sims EK, et al. Diabetes. 2022; 71: 610–623.

- DiMeglio LA, et al. Lancet. 2018; 391(10138): 2449–2462.

- Marré ML, et al. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2015; 3: 67.

- Ziegler AG, et al. JAMA. 2013; 309(23): 2473–2479.

- Fang M, et al. Ann Intern Med. 2023; 176(11): 1567–1568.

- Hormazabal-Aguayo I, et al. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2024; 40(3): e3749.

- Gregory GA, et al. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2022; 10(10): 741–760.

- TZIELD® (teplizumab) UK Summary of Product Characteristics. 2025.

MAT-XU-2500756 (v1.0) | November 2025