- Article

- Source: Campus Sanofi

- 1 Jan 2025

Fabrazyme® (agalsidase beta) evidence

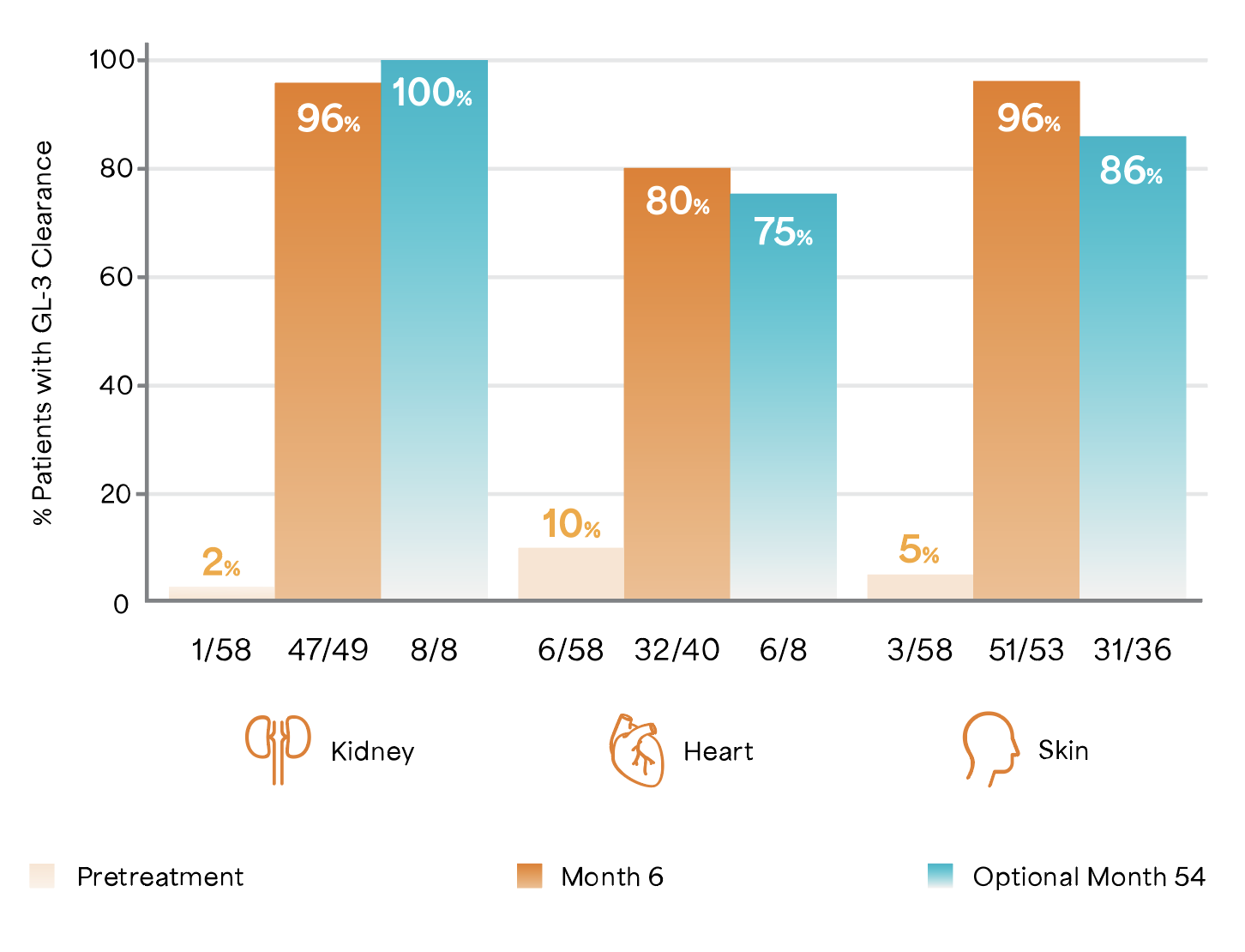

Rapid and sustained clearance of GL-3 in the kidney, heart, and skin1,2

Potential reduction of life-threatening events by 61%3

Protection from long-term progression of renal function decline4

Improved cardiac function5

Fabrazyme® cleared GL-3 in the kidney, heart, and skin in as quickly as 6 months after initiation6

Adapted from Germain D et al. 2007.6

Study Design: A randomized, 1:1, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of 58 patients with a diagnosis of Fabry disease, aged 16 to 61 years including 56 males, 2 females, naïve to ERT.7

Patients were randomized 1:1 to receive either 1 mg/kg of Fabrazyme® EOW or placebo for 5 months (20 weeks).6 All 58 patients were enrolled in the open-label extension study of 54 months in which they received biweekly 1 mg/kg Fabrazyme® infusions for up to an additional 54 months.6

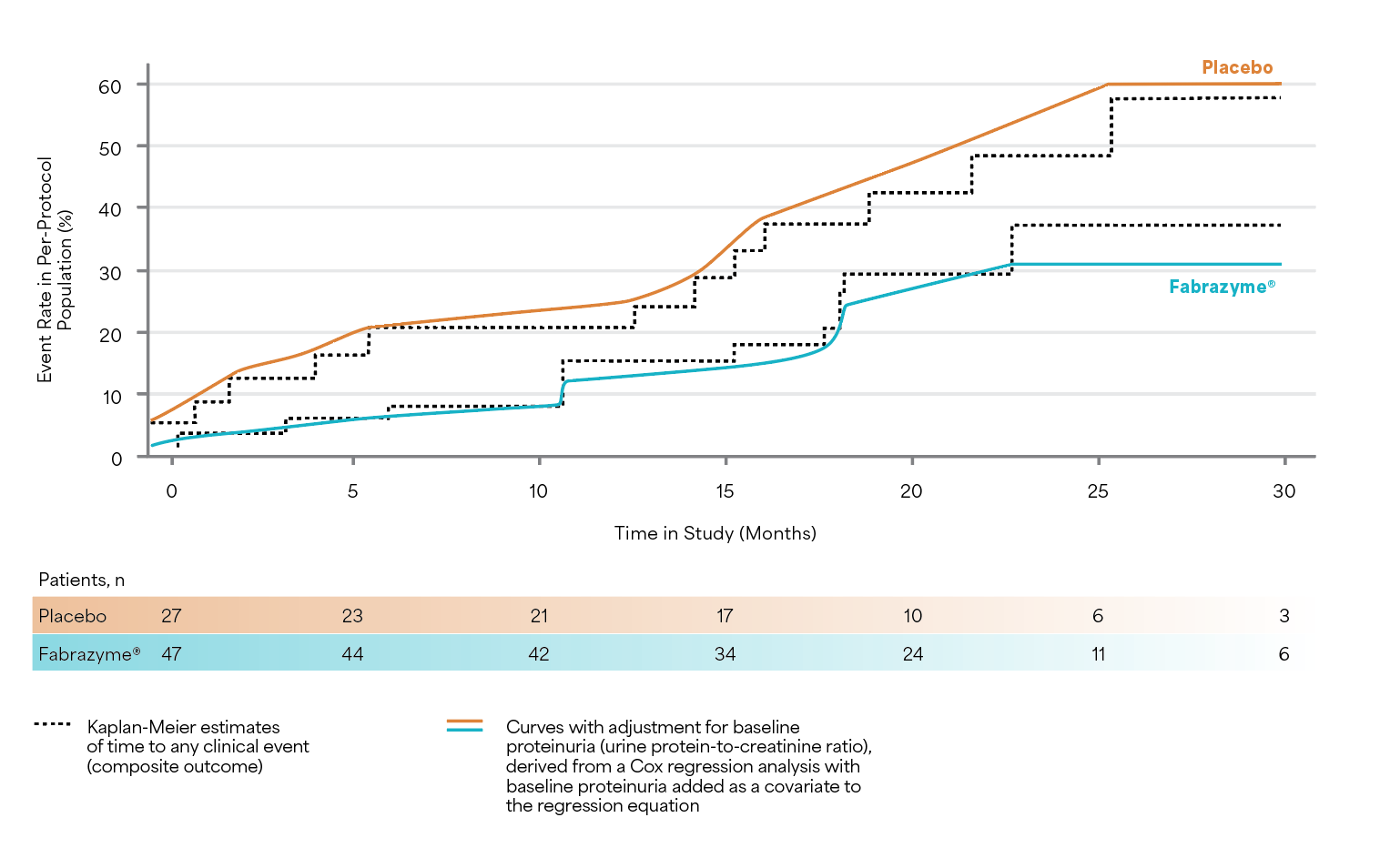

A potential reduction of life threatening events by 61%3

61% relative risk reduction of renal, cardiac and cerebrovascular life-threatening events and death in Fabrazyme®-treated patients vs. placebo.3 A smaller percentage of Fabrazyme®- treated patients (27%) experienced clinical events vs. placebo (42%).3 (Absolute risk reduction = 14%).3

Fabrazyme® substantially lowered the rate of renal, cardiac, and cerebrovascular clinical events among Fabrazyme®-treated vs. placebo-treated patients (risk reduction = 53% ITT population [HR 95% CI: 0.47 (0.21–1.03); p=0.06.3]; risk reduction = 61% per-protocol population [HR 95% CI: 0.39 (0.16–0.93); p=0.034.3]).3

The time-to-event analyses for the composite end point in both treatment groups in the per-protocol population3

Results are from the population of protocol-adherent patients who followed all of the clinical study guidelines after adjustment for baseline proteinuria.3

Adapted from Banikazemi M et al. 2007.3

Study Design: A multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study in which patients were randomized 2:1 to receive either agalsidase beta (1 mg/kg, n=51) or placebo (n=31) EOW for up to 35 months. The primary endpoint was time to first clinical event (renal, cardiac, or cerebrovascular event or death). Secondary analysis of protocol-adherent patients with mild-to-moderate kidney dysfunction at baseline who were adjusted for baseline proteinuria.3

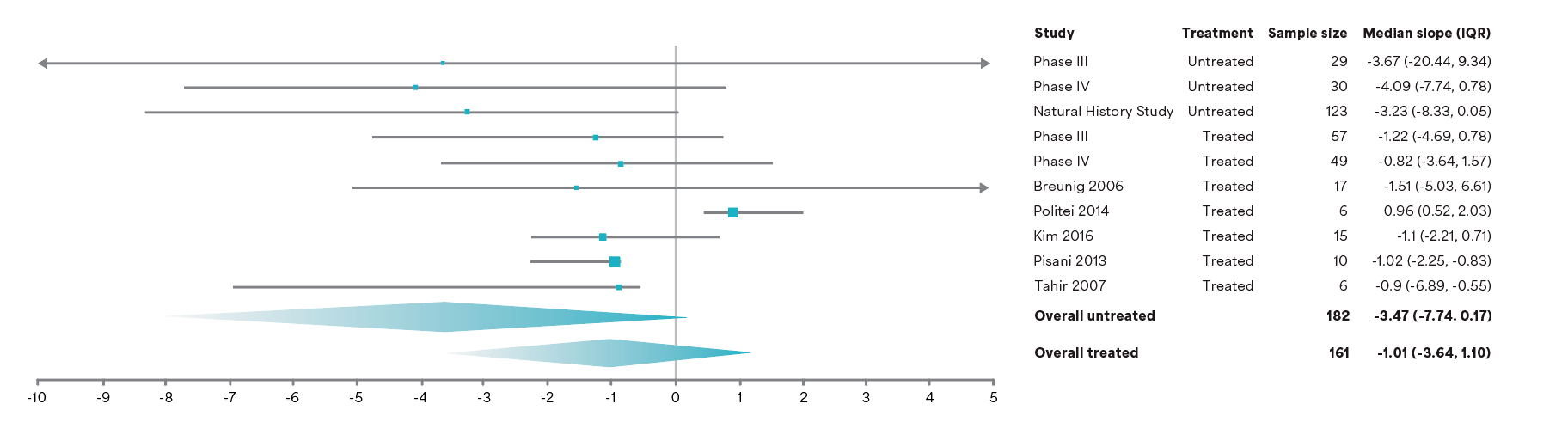

Protection from long term progression of renal function decline4

70.9% slower rate of eGFR decrease in Fabrazyme®-treated patients than a comparable untreated patient, after adjusting for the noted imbalances in gender and proteinuria.4 Fabrazyme®-treated classic Fabry disease patients experience a slower median eGFR decrease (2.46 mL/min/1.73m2/year, 95% CI: [0.63–4.29]; p=0.0087) than comparable untreated patients.4

Forest plot comparing the adjusted median eGFR slopes in Fabrazyme®-treated versus untreated patients4

Adjusted median eGFR slopes and IQR for the overall treated and untreated groups and the individual studies.

Adapted from Ortiz A et al. 2021.4

Study Design: A meta-analysis determining the effect of Fabrazyme® on loss of eGFR in the classic phenotype using a robust modeling approach and an expansive evidence base of individual patient-level data including four Sanofi-Genzyme studies and six studies from a systematic literature review (N=315 patients).4 Patients were required to have follow-up data for a minimum of 12 weeks, with 67 treated and 55 untreated patients having ≥4 years of follow-up.4

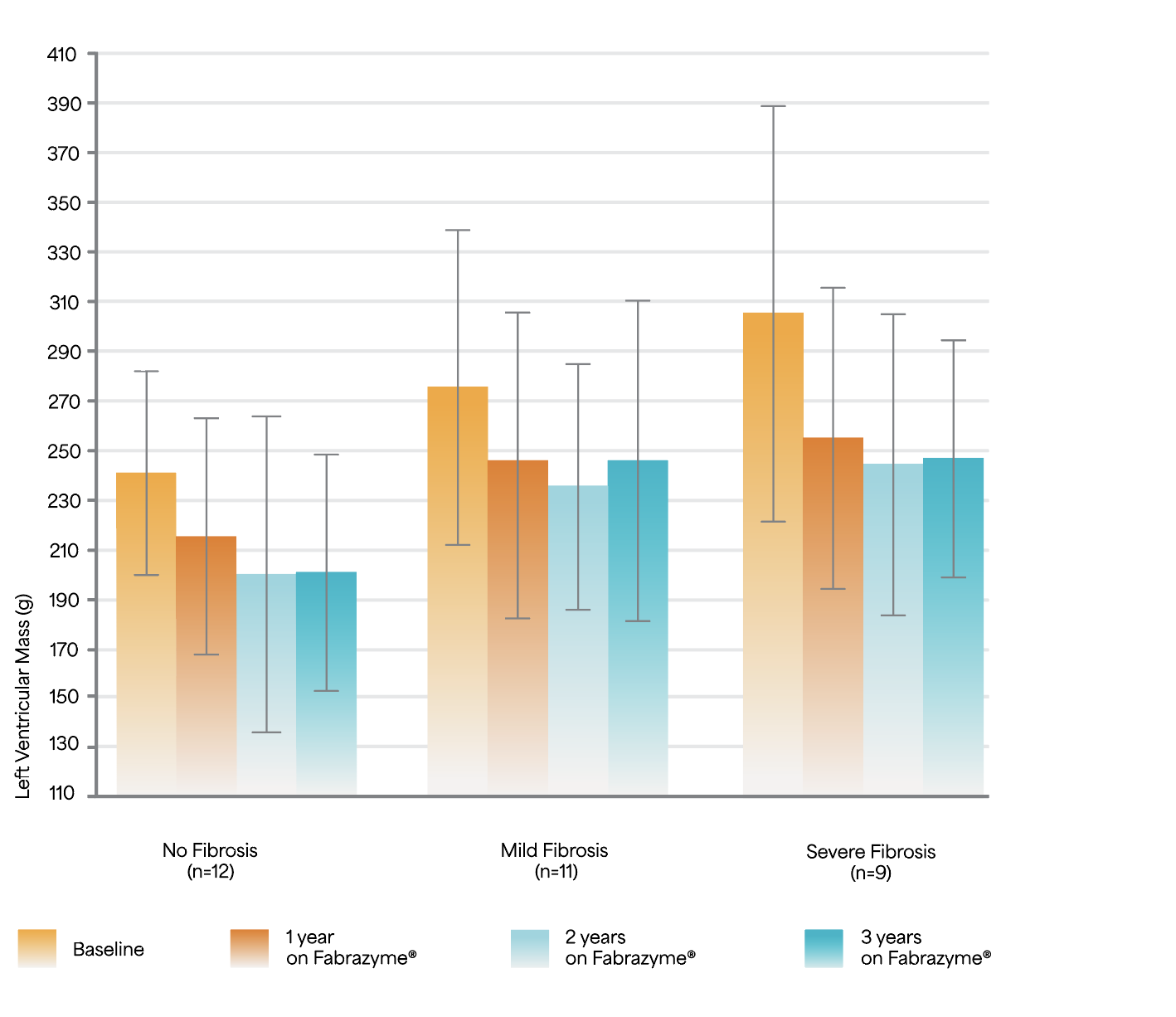

Early initiation with Fabrazyme®, before development of fibrosis, could help improve cardiac morphology, function, and exercise capacity5

Change in left ventricular mass during 3 years of ERT.5

Adapted from Weidemann F et al. 2009.5

Study Design: A prospective observational study of 32 ERT-naïve patients (mean age 42 years) treated with 1 mg/kg Fabrazyme® EOW for 3 years.5

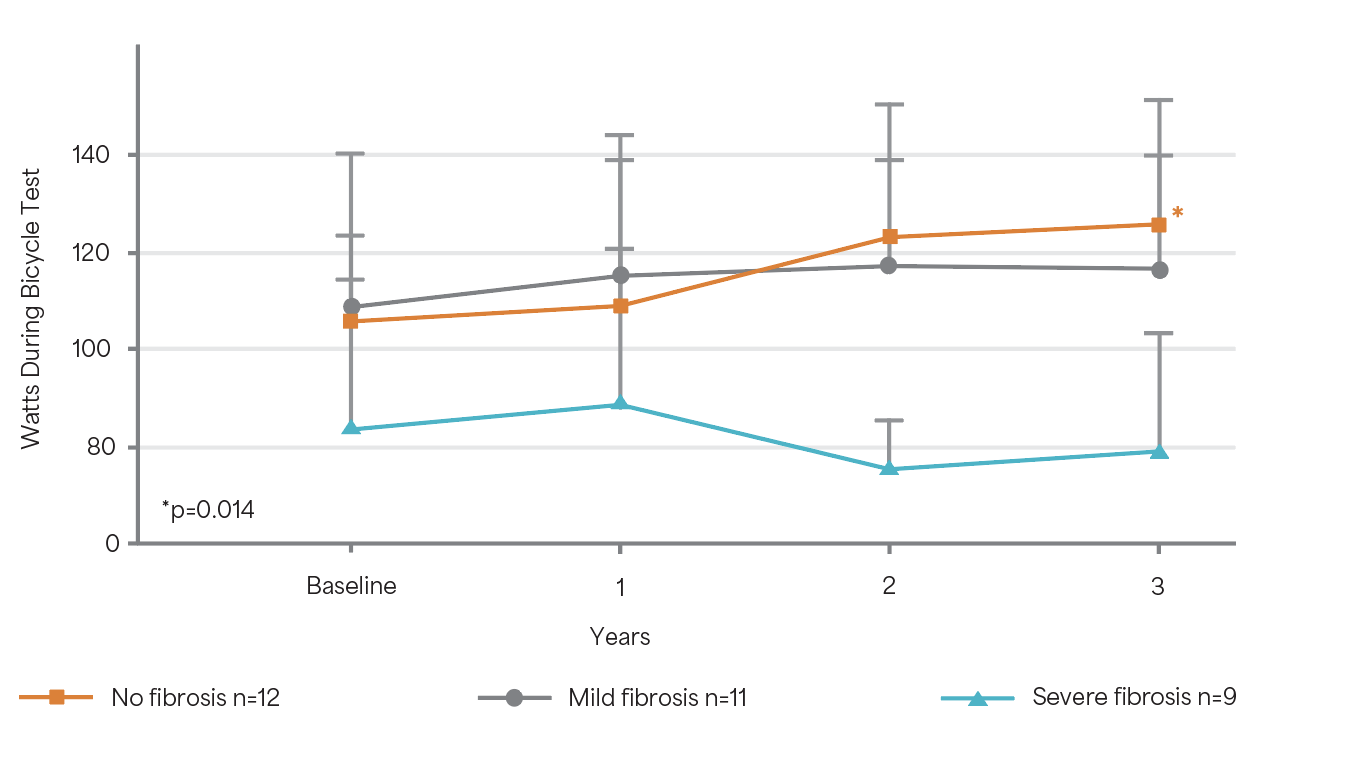

Change in exercise capacity during 3 years of ERT5

Adapted from Weidemann F et al. 2009.5

A mild but significant improvement in exercise capacity could be demonstrated for patients

with no fibrosis (p=0.014).5

Study Design: A prospective observational study of 32 ERT-naïve patients (mean age 42 years) treated with 1 mg/kg Fabrazyme® EOW for 3 years.5

Did you know?

Fabry disease starts early in the kidney and is a silent threat. Progressive accumulation of globotriaocylceramide (GL-3) leads to cellular changes and histological damage.8 Fabry nephropathy shows similarities to other proteinuric nephropathies of metabolic origin.3 Once the mechanisms leading to tissue injury are activated, the progression of Fabry nephropathy becomes irreversible.9,10

Learn more about Fabrazyme®

Fabrazyme® safety profile

Find out more about the safety and tolerability profile for Fabrazyme®.

Treatment with Fabrazyme®

Discover more about treatment with Fabrazyme® for patients living with Fabry disease.

Fabrazyme® safety profile

Find out more about the safety and tolerability profile for Fabrazyme®.

Treatment with Fabrazyme®

Discover more about treatment with Fabrazyme® for patients living with Fabry disease.

CI, confidence interval; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; EOW, every other week; ERT, enzyme replacement therapy; GL-3, globotriaosylceramide; HR, hazard ratio; IQR, interquartile range; ITT, intent-to-treat.

References

-

Eng CM et al. N Engl J Med 2001; 345(1): 9–16.

-

Thurberg B et al. Circulation 2009; 119(19): 2561–2567.

-

Banikazemi M et al. Ann Intern Med 2007; 146: 77–86.

-

Ortiz A et al. Clinical Kidney Journal 2021; 14 (4): 1136–1146.

-

Weidemann F et al. Circulation 2009; 119(4): 524–529.

-

Germain D et al. J Am Soc Nephrol 2007; 18(5): 1547–1557.

-

Eng CM et al. N Engl J Med 2001; 345(1): 9–16.

-

Waldek S and Ferriozi S. BMC Nephrol. 2014;15:72.

-

Ortiz A, et al. Mol Genet Metab. 2018;123(4):416–27.

-

Van der Veen SJ, et al. Mol Genet Metab. 2022;135(2):163–69

MAT-XU-2400636 (v2.0) Date of preparation: January 2025