- Article

- Source: Campus Sanofi

- Apr 28, 2025

Diagnosing TTP

Identifying thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura (TTP) among thrombotic microangiopathies (TMAs)

TMAs require urgent management, but variable presentation can make them difficult to distinguish1,2

TMA is a pathologic term used to describe occlusive microvascular or macrovascular disease, often with intraluminal thrombus formation.3 Presentation of TMAs varies widely, including but not limited to stroke, neurologic complications, severe renal failure, flu-like symptoms, and simple fatigue.4,5

This leads to the involvement of several physician specialists at the outset of patient care in clinic and hospital settings. Both—the variability of TMAs and the involvement of many specialties—pose a challenge to prompt recognition and diagnosis of TTP.4,5

Your role is crucial to the diagnosis and speed of appropriate treatment for TMAs6

In most cases, patients present at the emergency department for a nonspecific somatic complaint, and thrombocytopenia is subsequently discovered. More rarely, the results of a CBC can reveal thrombocytopenia during an appointment in a non-hospital setting.6

It is critical to suspect TMA when you see7,8:

Thrombocytopenia

(often platelets <30 × 109/L)

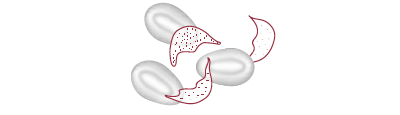

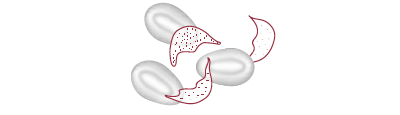

Microangiopathic hemolytic anemia (MAHA)

characterized by the presence of schistocytes in blood smear

Organ failure

of varying severity

Thrombocytopenia associated with MAHA should suggest a TMA syndrome, even in the absence of organ failure.9

Important TMA lab markers6,10,11

Biological report sheet

| Blood count | Thrombocytopenia | |

|

Hemolytic anemia | ||

|

Reticulocyte count |

High (>120 g/L)* | |

| Hemoglobin | Low | |

|

Schistocytes on blood smear |

Present† | A hallmark of TTP, but absence does not rule out a diagnosis |

|

Coombs test |

Negative‡ | |

|

Hemolysis evaluation | Hyperbilirubinemia | |

|

Haptoglobin low, even undetectable | ||

| High LDH rate§ | While not diagnostic, elevated LDH may predict organ damage | |

|

Hemostasis assessment |

Most often normal | |

| D-dimer rate may be moderately elevated |

Understanding the types of TMAs can change how you treat the patient1,12

TMAs are classified into 2 types: primary and secondary. Primary TMAs have no clear underlying cause, while secondary TMAs may be caused by a number of clinical conditions. Recognizing the underlying cause, or lack thereof, can determine treatment course.1,12

Types of TMAs1,12

Primary TMAs

- TTP (acquired/immune-mediated and hereditary)

- HUS (atypical/complement-mediated and Shiga toxin–producing E coli)

Secondary TMAs

- Systemic lupus erythematosus

- Pregnancy-associated (eg, hemolysis, elevated liver enzymes, low platelet count [HELLP] syndrome)

- Hematopoietic progenitor cell transplantation

- Drug-induced

The 2 primary TMAs—TTP and HUS—are often confused, but differentiating them is critical to determining appropriate treatment1,2

Historically, TTP and hemolytic uremic syndrome (HUS) were classified based on clinical findings: TTP for predominant neurologic involvement and HUS for the kidney-dominant diseases.1,13 With recent understanding of the molecular basis of TMAs, definitions have changed.1,7,8,11,13

-mobile.png)

TTP is now defined as

ADAMTS13 deficiency

vs

HUS may be caused by Shiga toxin-producing E coli (STEC-HUS)

OR

genetic mutations in complement regulatory proteins (atypical or complement-mediated HUS)

Differentiation of TTP from HUS can be confounded by kidney involvement in TTP. 25% of patients with TTP had kidney injury in the Oklahoma TTP Registry.5,14,15

Variable presentation of TMAs, potential confusion with HUS, and lack of diagnostic protocols can result in a missed or delayed diagnosis of aTTP2,16

-mobile.png)

of patients with aTTP were misdiagnosed 16

According to a retrospective review of the French Reference Centre for TMA registry (N=423).

This number may be underestimated due to the study being unable to exclude the possibility that some misdiagnosed patients may have died before their TTP diagnosis was made.16

|

The consequences of delayed diagnosis and treatment of TTP can be devastating, including organ failure or even death.7,11,15-17 |

aTTP=acquired thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura; CBC=complete blood count; E coli=Escherichia coli; LDH=lactate dehydrogenase.

*Emphasizes the regenerative nature of anemia.

†Nonsystematic presence of schistocytes, possibly late onset, hence the importance of repeating this test several times to increase the sensitivity of the examination.16

‡Test may turn out to be slightly positive in an autoimmune environment.16 §Related to hemolysis and organ tissue damage.6

-

Arnold DM, Patriquin CJ, Nazy I. Thrombotic microangiopathies: a general approach to diagnosis and management. CMAJ. 2017;189(4):E153-E159. doi:10.1503/cmaj.160142

-

Gallan AJ, Chang A. A new paradigm for renal thrombotic microangiopathy. Semin Diagn Pathol. 2020;37(3):121-126. doi:10.1053/j.semdp.2020.01.002

-

Scully M, Cataland S, Coppo P, et al. Consensus on the standardization of terminology in thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura and related thrombotic microangiopathies. J Thromb Haemostasis. 2017;15(2):312-322. doi:10.1111/jth.13571

-

Bommer M, Wölfle-Guter M, Bohl S, Kuchenbauer F. The differential diagnosis and treatment of thrombotic microangiopathies. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2018;115(19):327-334. doi:10.3238/arztebl.2018.0327

-

Coppo P, Veyradier A. Current management and therapeutical perspectives in thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura. Presse Med. 2012;41(3 pt 2):e163-e176. doi:10.1016/j.lpm.2011.10.024

-

Gardy O, Gay J, Pateron D, Coppo P. Les microangiopathies aux urgences. Presented at: Urgences 2014; June 4-6, 2014; Paris. Accessed February 18, 2022. https://www.sfmu.org/upload/70_formation/02_eformation/02_congres/Urgences/urgences2014/donnees/pdf/077.pdf

-

Joly BS, Coppo P, Veyradier A. Thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura. Blood. 2017;129(21):2836-2846. doi:10.1182/blood-2016-10-709857

-

Zheng XL, Vesely SK, Cataland SR, et al. ISTH guidelines for the diagnosis of thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura. J Thromb Haemost. 2020;18(10):2486-2495. doi:10.1111/jth.15006

-

Van der Linden T, Souweine B, Dupic L, Soufir L, Meyer P. Management of thrombocytopenia in the ICU (pregnancy excluded). Ann. Intensive Care. 2012;2(1):42. doi:10.1186/2110-5820-2-42

-

Azoulay E, Bauer PR, Mariotte E, et al; Nine-i Investigators. Expert statement on the ICU management of patients with thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura. Intensive Care Med. 2019;45(11):1518-1539. doi:10.1007/s00134-019-05736-5

-

Scully M, Hunt BJ, Benjamin S, et al; British Committee for Standards in Haematology. Guidelines on the diagnosis and management of thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura and other thrombotic microangiopathies. Br J Haematol. 2012;158(3):323-335. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2141.2012.09167.x

-

Radhakrishnan J. Anticomplement therapies in “secondary thrombotic microangiopathies”: ready for prime time? Kidney Int. 2019;96(4):833-835. doi:10.1016/j.kint.2019.08.00f

-

Tsai H-M. Pathophysiology of thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura. Int J Hematol. 2010;91(1):1-19. doi:10.1007/s12185-009-0476-1

-

George JN. The remarkable diversity of thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura: a perspective. Blood Adv. 2018;2(12):1510-1516. doi:10.1182/bloodadvances.2018018432

-

Kremer Hovinga JA, Vesely SK, Terrell DR, Lämmle B, George JN. Survival and relapse in patients with thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura. Blood. 2010;115(8):1500-1511. doi:10.1182/blood-2009-09-243790

-

Grall M, Azoulay E, Galicier L, et al. Thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura misdiagnosed as autoimmune cytopenia: causes of diagnostic errors and consequence on outcome. Experience of the French Thrombotic Microangiopathies Reference Centre. Am J Hematol. 2017;92(4):381-387. doi:10.1002/ajh.24665

-

Sayani FA, Abrams CS. How I treat refractory thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura. Blood. 2015;125(25):3860-3867. doi:10.1182/blood-2014-11-551580

How to diagnose thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura (TTP)

Diagnosing TTP rapidly is critical and can save a life1

When a patient presents with2

Severe thrombocytopenia

(often platelets <30 × 109/L).

Microangiopathic hemolytic anemia (MAHA)

characterized by the presence of schistocytes in blood smear

With no identified cause

The risk of death is acute and imminent if TTP remains undiagnosed and untreated1,3,4

of untreated patients1,3,4

of the acute event if untreated1

Why TTP can be difficult to diagnose

TTP is rare and presents similarly to other thrombotic microangiopathies (TMAs), making it a challenge to diagnose. All TMAs result in thrombosis of capillaries and arterioles due to endothelial injury.5,6

A delay in diagnosing TTP can leave patients at risk for organ damage and death. The uncertainty around what’s happening to these patients can cause fear and frustration.5,7-9

|

It's critical to differentiate TTP from other TMAs quickly so patients can get started on appropriate treatment |

Diagnosing TTP in adults: Step-by-step1,7,10-15

Presentation

Neurological symptoms

Headache and/or confusion and/or seizures and/or other cerebral abnormalities

Gastrointestinal symptoms

Abdominal pain, nausea, and diarrhea

Cardiac symptoms

Chest pain and/or hypotension and/or myocardial infarction and/or congestive heart failure and/or sudden cardiac arrest and/or other cardiac abnormalities

Renal impairment

Hematuria and proteinuria; creatinine <2 mg/dL; typically not severe

Diagnosing aTTP?

Important TTP lab markers

The presence of schistocytes on the blood smear is the morphologic hallmark of the disease, but the absence of schistocytes does not rule out TTP.2,16

.png)

Although serum creatinine is typically <2.0 mg/dL at presentation, the Oklahoma TTP-HUS Registry reported kidney injury 25% of the time.2,15

%20(1).png)

While not diagnostic, elevated LDH may be predictive of severe organ damage, and elevated troponin may indicate cardiovascular risk.1,2

%20(1)%20(1).png)

ADAMTS13 activity <10% confirms a TTP diagnosis and supports TTP treatment, but ADAMTS13 levels of 10% to 20% do not rule out TTP. TTP management will rely on clinical judgment.2,7,13

|

ADAMTS13 <10% confirms TTP. Test as soon as possible when TMA is suspected.2,7,13 |

LDH=lactose dehydrogenase; MAHA=microangiopathic hemolytic anemia; TMA=thrombotic microangiopathy; TTP=thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura.

-

Scully M, Hunt BJ, Benjamin S, et al; British Committee for Standards in Haematology. Guidelines on the diagnosis and management of thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura and other thrombotic microangiopathies. Br J Haematol. 2012;158(3):323-335. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2141.2012.09167.x

-

Joly BS, Coppo P, Veyradier A. Thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura. Blood. 2017;129(21):2836-2846. doi:10.1182/blood-2016-10-709857

-

Kremer Hovinga JA, Vesely SK, Terrell DR, Lämmle B, George JN. Survival and relapse in patients with thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura. Blood. 2010;115(8):1500-1511. doi:10.1182/blood-2009-09-243790

-

Sayani FA, Abrams CS. How I treat refractory thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura. Blood. 2015;125(25):3860-3867. doi:10.1182/blood-2014-11-551580

-

Arnold DM, Patriquin CJ, Nazy I. Thrombotic microangiopathies: a general approach to diagnosis and management. CMAJ. 2017;189(4):E153-E159. doi:10.1503/cmaj.160142

-

Tsai H-M. Pathophysiology of thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura. Int J Hematol. 2010;91(1):1-19. doi:10.1007/s12185-009-0476-1

-

Zheng XL, Vesely SK, Cataland SR, et al. ISTH guidelines for the diagnosis of thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura. J Thromb Haemost. 2020;18(10):2486-2495. doi:10.1111/jth.15006

-

Grall M, Azoulay E, Galicier L, et al. Thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura misdiagnosed as autoimmune cytopenia: causes of diagnostic errors and consequence on outcome. Experience of the French Thrombotic Microangiopathies Reference Centre. Am J Hematol. 2017;92(4):381-387. doi:10.1002/ajh.24665

-

Gallan AJ, Chang A. A new paradigm for renal thrombotic microangiopathy. Semin Diagn Pathol. 2020;37(3):121-126. doi:10.1053/j.semdp.2020.01.002

-

Sukumar S, Lämmle B, Cataland SR. Thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura: pathophysiology, diagnosis, and management. J Clin Med. 2021;10(3):536. doi:10.3390/jcm10030536

-

Wiernek SL, Jiang B, Gustafson GM, Dai X. Cardiac implications of thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura. World J Cardiol. 2018;10(12):254-266.

-

Hawkins BM, Abu-Fadel M, Vesely SK, George JN. Clinical cardiac involvement in thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura: a systematic review. Transfusion. 2008;48:382-392. doi:10.1111/j.1537-2995.2007.01534.x

-

Supplement to (Acquired TTP): George JN. The remarkable diversity of thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura: a perspective. Blood Adv. 2018;2(12):1510-1516. doi:10.1182/bloodadvances.2018018432

-

Supplement to (Approach to Patient): George JN. The remarkable diversity of thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura: a perspective. Blood Adv. 2018;2(12):1510-1516. doi:10.1182/bloodadvances.2018018432

-

George JN. The remarkable diversity of thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura: a perspective. Blood Adv. 2018;2(12):1510-1516. doi:10.1182/bloodadvances.2018018432

-

Azoulay E, Bauer PR, Mariotte E, et al; Nine-i Investigators. Expert statement on the ICU management of patients with thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura. Intensive Care Med. 2019;45(11):1518-1539. doi:10.1007/s00134-019-05736-5

Guidelines for diagnosing and treating thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura (TTP)

The International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis (ISTH) published guidelines are the first comprehensive, evidence-based, international guidelines on the diagnosis, treatment, and management of TTP.1

Most recent publication

The ISTH Guidelines for Diagnosis and Treatment were published July 2020.

About ISTH

With more than 5000 members across 100 countries, the ISTH is the leading thrombosis and hemostasis–related professional organization in the world.2

Why the ISTH Guidelines were developed

Diagnosing and treating TTP can be complicated.1

- The rarity of TTP—and its similar presentation to other TMAs—can make recognition a challenge info icon

- Management of TTP varies among healthcare professionals (HCPs)

- Treatment recommendations in TTP have evolved

ISTH created the guidelines as a comprehensive, uniform, international resource to inform the diagnosis and management of TTP1

The ISTH Guidelines can aid HCPs—both those with limited experience with TTP and those considered experts in TTP—in making a TTP diagnosis and following an appropriate treatment strategy.

These include1

- Emergency/critical care physicians

- Hematologists

- Nephrologists

- Neurologists

- Transfusion medicine specialists

- Hospitalists

- Policy makers

|

The ISTH has created the first evidence-based guidelines to support rapid TTP diagnosis and treatment. |

-

Zheng XL, Vesely SK, Cataland SR, et al. ISTH Guidelines for the diagnosis of thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura. J Thromb Haemost. 2020;18(10):2486-2495. doi:10.1111/jth.15006

-

ISTH History. International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis website. Accessed November 16, 2021. http://www.ISTH.org/page/History

MAT-KW-2500518-V1-Nov-25