- Article

- Source: Campus Sanofi

- May 1, 2024

A Multidisciplinary Approach to Fabry Disease Care

A multidisciplinary approach to Fabry disease care

Symptom management may help to reduce the burden of Fabry disease. The coordination of care involves a multidisciplinary approach which may include a geneticist, genetic counselor, nephrologist, neurologist, and cardiologist, as well as other healthcare professionals.1

It's important that each specialist monitor patients with Fabry disease for emergence of new symptoms as well as tracking existing symptoms. The Fabry disease Schedule of Assessments provides guidance on monitoring symptoms in patients with Fabry.

Fabry disease in your practice

Patients with Fabry disease often have a variety of symptoms and clinical manifestations across multiple organ systems. Consequently, patients are often referred to specialists for further evaluation, and specialists may be first to raise suspicion of and ultimately diagnose Fabry disease.

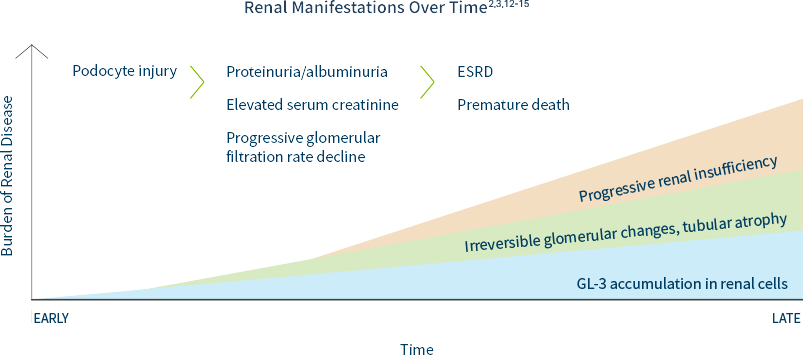

Nephrology

Kidney disease is a major complication of Fabry Disease.2,3 The prevalence of Fabry disease in the dialysis population is approximately 100 to 1000 times higher than in a reference population.4-8 Patients with Fabry disease are at high risk of progressing to end-stage renal disease (ESRD) at a young age (typically 30s to 50s but ESRD has been reported as early as teen years).9 The prevalence of chronic kidney disease (CKD) in patients with Fabry disease is approximately 5 times higher than in the general population.10,11

Renal damage as a result of GL-3 accumulation in various renal cells can start as early as the first decade of life, often preceding laboratory abnormalities and clinical symptom onset.3,11

In males and females, progressive accumulation of GL-3 in podocytes, followed by podocyte injury, manifests later as proteinuria and reduced glomerular filtration rate, which can ultimately lead to CKD or progression to end-stage renal disease (ESRD).12,13

Including Fabry disease in the differential diagnosis of unexplained ESRD is key to identifying patients and families.

European Renal Best Practice recommends screening males under age 50 with unexplained CKD and females of any age with unexplained CKD and other symptoms associated with Fabry disease.16

If you have a patient that you suspect may have Fabry disease, consider having them and their family tested.

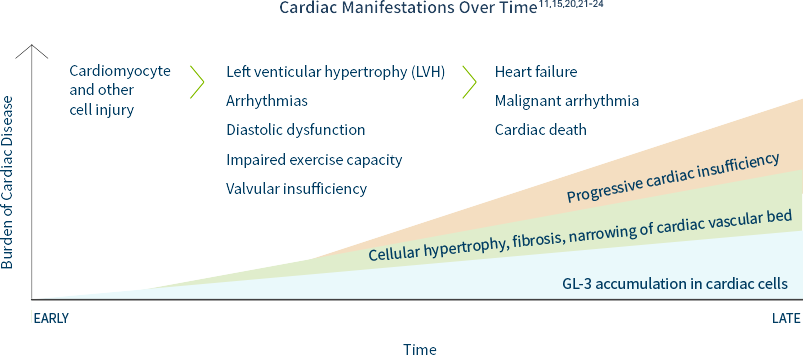

Cardiology

Cardiac disease is the most common cause of death in patients with Fabry disease.11 Unexplained cardiac manifestations could indicate Fabry disease. The prevalence of Fabry disease in patients with left ventricular hypertrophy (LVH) or hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM) is estimated to be at least 1 in 100.17-19

In a natural history study of 279 males and 168 females with FD, forty-nine percent of males and 35% of females with the disease were found to have had a cardiac event by an average age of 36 years and 44 years respectively.15

Cardiac hypertrophy, fibrosis, and conduction abnormalities can be caused by GL-3 accumulation in cellular components of the heart, adversely affecting cardiac structure and function. Other cardiac manifestations may include: EKG abnormalities, short PR intervals, AV block, repolarization abnormalities, ST-T changes, and/or arrhythmias.20 Persistent accumulation of GL-3 in cardiomyocytes over time may lead to LVH, ultimately resulting in heart failure.21

Including Fabry disease in the differential diagnosis of unexplained LVH or HCM is key to identifying patients and families.

The European Society of Cardiology guidelines recommend a systematic search for the underlying cause of increased LV wall thickness, including specialized laboratory testing and genetic analysis.25 Screening patients with unexplained LVH or HCM for Fabry disease is key to identifying patients and families.

If you have a patient that you suspect may have Fabry disease, consider having them and their family tested.

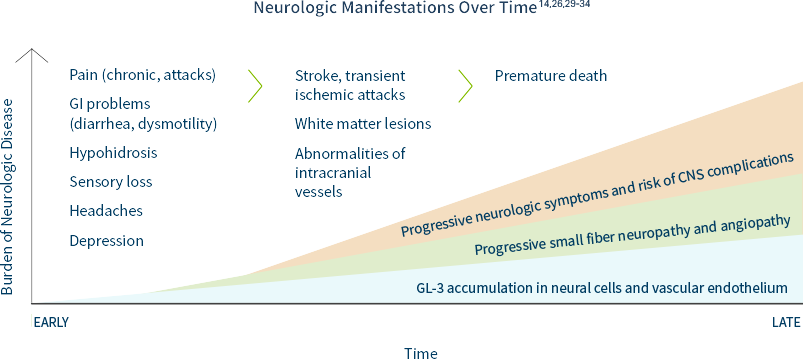

Neurology

Prevalence estimates of Fabry disease in patients with premature stroke range from 1% to nearly 5%, much higher than in the general population.26

Based on registry data, the median age of the first stroke is 39 years in men and 46 years in women.29

In Fabry disease, GL-3 can accumulate in peripheral and central neurons as well as cerebral blood vessels, causing26,27:

- Neuropathic pain and autonomic symptoms, due to damage to peripheral neurons and axons

- White matter lesions

- Cognitive impairment, anxiety, depression

PNS: Neuropathic Pain

GL-3 accumulation causes neural damage primarily involving the small nerve fibers of the peripheral somatic and autonomic nerve systems. Pain is one of the earliest symptoms of Fabry, affecting 60% to 80% of classically affected boys and girls, which affects their quality of life. Boys generally have an earlier age of related symptom onset than girls. Two types of pain have been described14:

- Episodic crises ("Fabry crises")—agonizing burning pain originating in the extremities and radiating inward to the limbs and other parts of the body

- Chronic pain—burning and tingling paraesthesia

CNS Complications

The early peripheral neuropathic hallmarks of Fabry disease are often followed by cerebrovascular complications and autonomic dysfunction in adulthood.14

Fabry disease is often misdiagnosed as multiple sclerosis (MS) due to white matter lesions.26,28

Some of the most devastating neurological features of Fabry disease are caused by cerebrovascular lesions, which are the result of multifocal involvement of small blood vessels. Cerebrovascular involvement can lead to a wide variety of signs and symptoms ranging from mild to severe, including headache, vertigo/dizziness, transient ischemic attacks, and ischemic strokes.14

If you have a patient that you suspect may have Fabry disease, consider having them and their family tested.

Eye Care Specialties

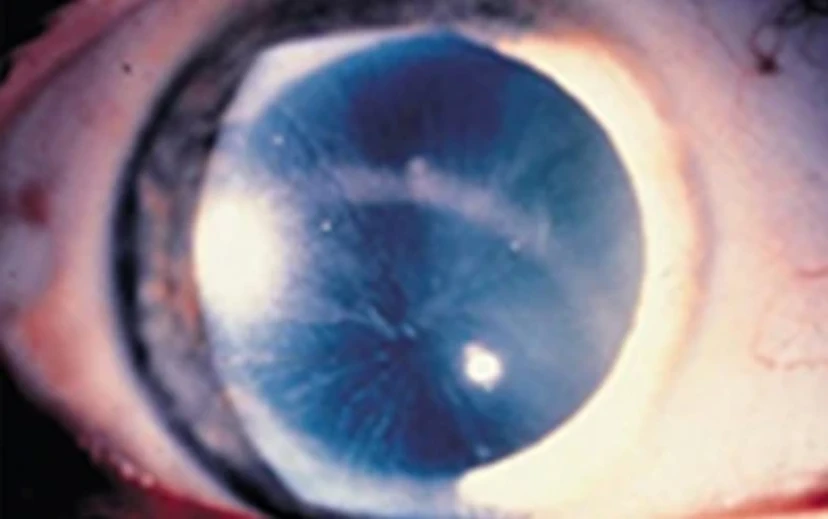

GL-3 and other lipids may deposit in the eyes of Fabry disease patients, resulting in a wide range of ocular findings. These findings typically do not affect the patient's vision but may be pathognomonic for Fabry disease.35,37

One of the earliest and most common signs of Fabry disease is corneal whorling, seen in 80% of patients with classic Fabry disease. The earliest report in boys is age 2 and in girls is age 6. Corneal whorling can be detected with a routine slit lamp examination.35

Distinctive Corneal Verticillata in Fabry 19,35,37

Corneal whorling is a symmetric, bilateral, whorl-like pattern of powdery, white, yellow, or brown corneal epithelial GL-3 deposits emanating from a single vortex.35

A number of medications, such as amiodarone and chloroquine, can also cause this phenomenon. Patients with Fabry disease may suffer from arrhythmias; therefore, Fabry should not be ruled out in a patient found to be on amiodarone.

In addition to corneal opacities, patients with Fabry disease may present with35:

- Posterior capsular cataracts with whitish spoke-like deposits of granular material (Fabry cataract)

- Aneurysmal dilatation of thin-walled venules on the bulbar conjunctiva

- Mild-to-marked tortuosity and angulation of the retinal vessels

Watch the video below to learn more about the ocular manifestations that can occur in Fabry disease

Please note: Corneal whorling shown is as seen as through slit lamp exam

Dermatology

The most recognizable clinical feature of Fabry disease is angiokeratomas, which have the following characteristics36,37:

- Dark red or purple skin lesions

- Range in size from a pinpoint to several millimeters in diameter

- Do not blanch with pressure

- Are usually distributed on the buttocks, groin, umbilicus, and upper thighs (bathing suit distribution)

Angiokeratomas in Fabry disease36,37

Characteristic dark red to blue-black angiectases are typically found between the thigh (left) and umbilicus (right) regions ("bathing suit distribution").

Images used with permissions from R.J. Desnick, MD, PhD.

Angiokeratoma generally appear in adolescence or young adulthood and may become larger and more numerous with age.37 Angiokeratomas are almost universal in classic male hemizygotes; they occur in approximately 30% of classic females.36

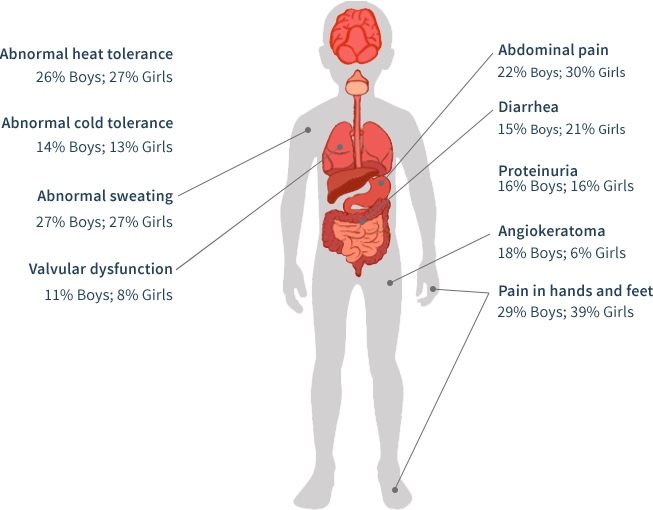

Pediatrics

Accumulation of GL-3 may begin in utero and continue over a lifetime. Clinical onset of classic Fabry disease occurs in childhood, and presentation may be subtle. Signs and symptoms are often discounted as malingering or are mistakenly attributed to other disorders, such as rheumatic fever, erythromelalgia, neurosis, Raynaud's syndrome, multiple sclerosis, chronic intermittent demyelinating polyneuropathy, lupus, acute appendicitis,"growing pains," or petechiae.37

The early clinical course of Fabry disease typically involves signs and symptoms that primarily affect quality of life: chronic pain, angiokeratomas, hypohidrosis, heat and cold intolerance, and gastrointestinal symptoms.37,38

Pain is one of the earliest symptoms of Fabry, affecting 60% to 80% of classically affected boys and girls, which affects their quality of life. Boys generally have an earlier age of related symptom onset than girls.14

An often overlooked manifestation of Fabry disease is the presence of GI symptoms, including abdominal pain (often after eating), diarrhea, nausea, and vomiting, which are a significant cause of anorexia. Diarrhea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) is a differential diagnosis.14

In a pediatric study based upon the Fabry Registry, boys and girls with Fabry disease begin developing symptoms at an early age (median age of 6 years for boys [n=194] and median age of 9 years for girls [n=158]). Moreover, some may have early severe complications.39

Primary Care

Primary care professionals (PCPs) often have the most frequent contact with patients. PCPs are often In the best position to first observe the cluster of seemingly unrelated signs and symptoms associated with Fabry disease. PCPs can help end a long patient journey in a proper diagnosis. Consequently, it is important they be aware of the common presenting symptoms for Fabry disease.

Common Presenting Signs and Symptoms for Fabry 14,37,38

- Fatigue

- Gastrointestinal problems such as abdominal pain, diarrhea, vomiting, and nausea

- Heat and cold intolerance

- Decreased ability to sweat (hypohidrosIs/anhidrosis)

- Neuropathic pain in the hands and feet, or acute agonizing episodes of radiating pain in the extremities or abdomen ("Fabry crises”) lasting for minutes or days

- Recurrent fever accompanying pain and associated with elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate

- A more specific sign of Fabry disease that may be seen in adolescents and adults is the presence of angiokeratomas—dark reddish-purple skin lesions that do not blanch with pressure

- Depression

These presenting symptoms in conjunction with a family history of early renal or cardiac disease, or stroke should raise a high suspicion of Fabry disease.

Gastroenterology

Gastrointestinal (GI) symptoms of Fabry disease may be related to the deposition of GL-3 in the autonomic ganglia of the bowel and mesenteric blood vessels.14

Despite being common, GI symptoms remain an under recognized manifestation of Fabry. Up to two-thirds of affected males and about half of symptomatic females may experience GI symptoms associated with classic Fabry disease.14,40,41 GI symptoms often appear In childhood and usually remain present during adulthood.

Patients may complain of abdominal pain (often after eating), diarrhea, nausea, and vomiting, which are a significant cause of anorexia. Diarrhea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) is a differential diagnosis.14

Rheumatology

Fatigue and pain may masquerade as rheumatological conditions such as lupus, chronic fatigue syndrome, and rheumatoid or juvenile arthritis.42 In a rheumatology setting, the most common presenting symptoms of Fabry disease are14,36,37,43:

- Joint pain

- Acute and chronic hand or foot pain, or acute agonizing episodes of radiating pain in the extremities lasting minutes to days ("Fabry crises")

- Angiokeratomas: Dark reddish-purple skin lesions that do not blanch with pressure and may resemble vasculitis

- Recurrent fever accompanying pain and associated with elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate

References: 1. Peters FPJ et al. Postgrad Med J. 1997;73(865):710-712. 2. Ortiz A et al. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2008;23(5):1600-1607. 3. Ramaswami U et al. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2010;5(2):365-370. 4. Nakao S et al. Kidney Int. 2003;64(3):801-807. 5. Linthorst GE et al. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2003;18(8):1581-1584. 6. Kotanako P et al. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2004;15(5):1323-1329. 7. Ichinose M et al. Clin Exp Nephrol. 2005;9(3):228-232. 8. Bekri S et al. Nephrol Clin Pract. 2005;101(1):33-38. 9. Wilcox WR et al. Mol Genet Metab. 2008;93(2):112-128. 10. Coresh J et al. JAMA. 2007;298(3):2038-2047. 11. Waldek S et al. BMC Nephrol. 2014;15(72):1-25. 12. Najafian B et al. Kidney Int. 2011;79(6):663-670. 13. Torra R. Kidney Int. 2008;(Suppl. 111):S29-S32. 14. Germain DP. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2010;5(30):1-49. 15. Schiffmann R et al. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2009;24(7):2102-2111. 16. Terryn W et al. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2013;28(3):505-517. 17. Linthorst GE et al. J Med Genet. 2010;47(4):217-222. 18. Monserrat L et al. Coll Cardiol. 2007;50(25):2399-2403. 19. Van der Tol L et al. J Met Genet. 2014;51(1):1-9. 20. Yousef Z et al. Eur Heart J. 2013;34(11):802-808. 21. Eng CM et al. Genet Med. 2006;8(9):539-548. 22. Patel MR et al. J Am Coll Cardiol 2011;57(9):1093-1099. 23. Kampmann C et al. Int J Cardiol. 2008;130(3):367-373. 24. Weidemann F et al. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2013;8(116). 25. Elliott PM et al. Eur Heart J. 2014;35(39):2733-2779. 26. Fellgiebel A et al. Lancet Neurol. 2006;5(9):791-795. 27. Hilz MJ. Clin Ther. 2010;32(Suppl C):S93. 28. Bottcher T et al. Plos ONE. 2013;8(8):e71894. 29. Sims K et al. Stroke. 2009;40(3):788-794. 30. Cable WJL et al. Neurology. 1982;32(5):498-502. 31. Uceyler N et al. Clin J Pain. 2014;30(10):915-920. 32. Fellgiebel A et al. Neurology. 2009;72(1):63-68. 33. Moore DF et al. Brain Res Bull. 2003;62(3):231-240. 34. Cole AL et al. J Inhewrit Metab Dis. 2007;30(6):943-951. 35. Samiy N et al. Surv Ophthalmol. 2008;53(4):416-423. 36. Desnick RJ et al. In: The Online Metabolic and Molecular Bases of Inherited Diseases. New York, NY: McGraw Hill; 2014:1-64. 37. Desnick RJ et al. Ann Intern Med. 2003;138(4):338-346. 38. Genzyme Corporation. Fabry Registry Annual Report. 2010. 39. Hopkin RJ et al. Pediatr Res. 2008;6495:550-555. 40. MacDermot KD et al. J Med Genet. 2001a;38(11):750-760. 41. MacDermot KD et al. J Med Genet. 2001b;38(11):769-775. 42. Laney DA et al. J Genet Couns. 2008;17(1):79-83. 43. Manger B et al. Clin Rheumatol. 2007;26(3):335-341.

MAT-US-2508632-v1.0-08/2025