- Artikel

- Bron: Campus Sanofi

- 14 nov 2024

The Complex Burden of Autoimmune Type 1 Diabetes

People who develop autoimmune Type 1 Diabetes (T1D) face a lifelong, multi-facetted burden that is both physical and psychological.

If the person who is diagnosed is a child or adolescent, this burden often affects the child’s entire family, as well as the child’s social relations such as daycare, school, and friends.

The burden of autoimmune T1D spans aspects related to the natural course of the condition, incl. how it progresses, how it is managed, and how it may cause complications. How autoimmune T1D progresses is generally determined by factors like HbA1c, Time in Range, and glucose variability, which in turn are determined by adequate administration of insulin and adherence to diet and exercise guidelines.1

The burden also has psychological aspects – from the impact of discovering a risk of developing autoimmune T1D, to the emotional toll of receiving a diagnosis, to the mental effects of daily management of a chronic condition, and to the potential impact of complications on the future of the individual.

DKA: diabetic ketoacidosis

Illustration produced by Sanofi based on references a-i:

a. Rawshani A et al. (2018) Lancet. 392, pp.477-86; b. Duca LM, et al. Diabetes Care. 2017;40(9):1249-55; c. Shrivastava SR et al. (2013) J Diabetes Metab Disord. 1214; d. Hammersen J et al. (2022) Pediatr Diabetes 22(3), pp.455-62; e. Aye T et al. (2019) Diabetes Care. 42(3), pp.443-9; f. Butwicka A, et al. (2015) Diabetes Care 38, 453-9; g. Fleming M et al. (2019) Diabetes Care. 42(9), pp.1700-7; h. Nielsen HB et al. (2016) Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 121, pp.62-8; i. Dehn-Hindenberg A et al. (2021) Diabetes Care. 44(12), pp.2656-63.

The Physical Burden of Autoimmune T1D & the Persistent Risk of Complications

Many people experience that being diagnosed with autoimmune T1D has a profound negative impact on the life of the individual and their entire family.2-8

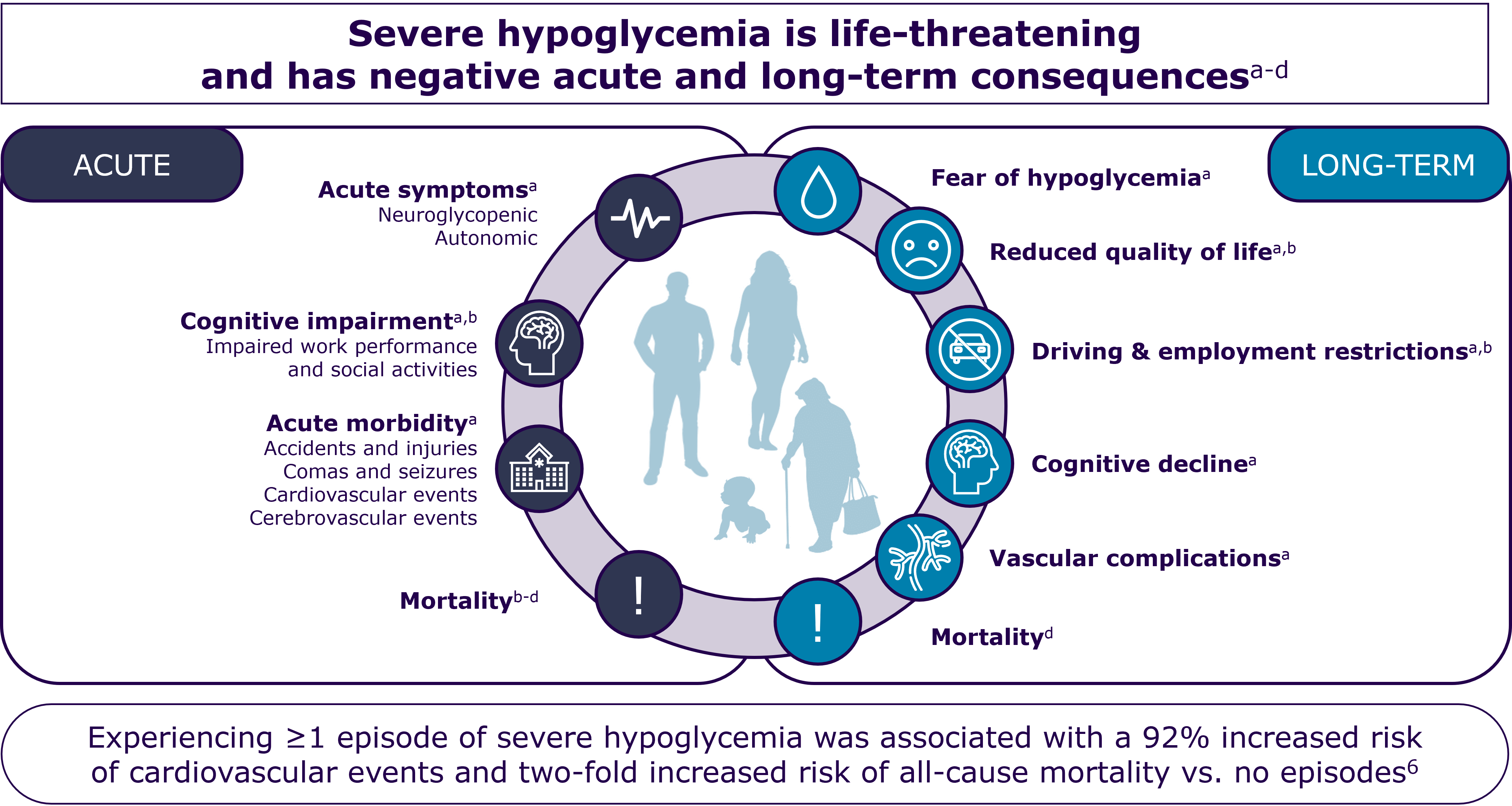

Despite advances in care and management of this chronic condition, autoimmune T1D continues to be associated with substantial medical burden, led by persistent risks of complications that may arise from blood glucose levels being out of range, incl.: 4-7, 9-16

- Hypoglycemia

- Retinopathy

- Neuropathy

- Nephropathy

- Increased risk of cardiovascular disease

- Sub-clinical brain alterations and detrimental neurocognitive outcomes

- Potentially life-threatening diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA)

- Increased morbidity and mortality

a. Frier BM (2014) Nat Rev Endocrinol, 10711-22; b. Seaquist ER et al. (2013) Diabetes Care, 36,pp.1384-1395; c. Cryer PE (2012) Diabetes Care, 35,pp.1814-1816; d. Khunti K et al. (2015) Diabetes Care, 38(2),pp.316-322.

Among the first complications that may arise for people who develop autoimmune T1D is diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA) – a potentially life-threatening condition that often requires hospitalization.11, 17

DKA prevention is considered to be important, because even DKA episodes that are not immediately life-threatening can have long-term effects. DKA at diagnosis of autoimmune T1D presents an acute complication, and DKA can lead to acute kidney injury or may negatively impact cognitive development of children and adolescents.11-13, 18, 19

Studies have found that whereas incidences of severe hypoglycemia have declined over the last years, the rate of DKA in people diagnosed with autoimmune T1D remains stable.12

Challenges in Daily Self-Management of Autoimmune T1D

Many who are diagnosed with autoimmune T1D find that daily self-management imposes a burden, as self-management requires a large number of repetitive – and potentially challenging – tasks that can be overwhelming, e.g. blood glucose-monitoring, insulin administration, adherence to restrictive diets, and regular physical exercising.20

Daily life for anyone with autoimmune T1D has been estimated to require upwards of 180 health-related decisions by each affected individual.21, 22 These decisions stem from at least 42 factors that are known to affect blood glucose levels. Several of these factors can be adjusted by or for the person living with autoimmune T1D, but many cannot, e.g. the menstrual cycle, weather conditions, or other autonomous processes happening in the body.23, 24

Blood glucose-monitoring and insulin administration tasks account for the largest part of the many daily, health-related decisions that must be made by people affected by autoimmune T1D. In this, the currently most common route of insulin administration (subcutaneous insulin injections) is associated with additional challenges such as injection pain, needle phobia, lipodystrophy, compliance difficulties, and peripheral hyperinsulinemia.25

As autoimmune T1D is a chronic condition, the relentlessness of self-management – combined with the astonishing number of daily health-related decision that people must make – can lead to feelings of not doing enough, i.e. feelings of self-mismanagement.20, 21

People with autoimmune T1D report that self-management imposes loss of freedom and lack of spontaneity,20 and it remains a recurring challenge for many to successfully self-manage and achieve blood glucose levels in accordance with guidelines.26

Even with the advent of modern insulin analogs and advanced technologies designed to enable more appropriate reaction to more precise blood glucose-monitoring, it is suggested that technological improvements have elevated the focus on blood glucose management and increased the time spent on self-management, which then adds to the burdensome feelings that decrease quality of life.26, 27

Psychosocial Impact of Autoimmune T1D

As autoimmune T1D is a mentally demanding condition, psychosocial challenges affect people who live with the condition considerably more than such challenges affect the general population.20

At any time, up to 40% of individuals living with the autoimmune T1D are affected by diabetes-related distress,20 which refers to the emotional burden and stress resulting from the ongoing demands of managing diabetes daily.28

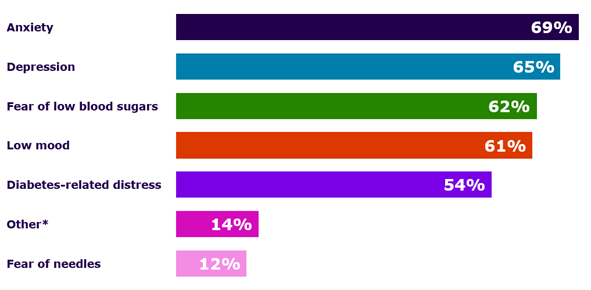

A study of self-reported survey data found that people experienced several types of emotional distress as part of the psychosocial burden of living with diabetes (autoimmune T1D or Type 2 Diabetes):20

Graph reproduced by Sanofi based Kelly RC, et al. (2023) (Fig. 1)20

* The ‘Other’ responses in this study refer to the 14% of self-reporting people with diabetes who experienced a psychosocial burden from feelings of anger, PTSD, disordered eating, fear of high blood sugars, marriage problems, mental fatigue, burnout/feeling overwhelmed/hopelessness, and suicidal thoughts.20

A systematic review and meta-analysis that compared depression prevalence in >1 million individuals with and without diabetes found that the prevalence of diagnosed depression to be significantly higher in people with autoimmune T1D (22% versus 13% in people who were not affected by the condition). These findings were consistent when rates were determined by gender, type of diabetes, method of diabetes and depression assessment, and study setting.29

Connecting the physical burden of autoimmune T1D with the psychosocial burden of ditto, several bodies of research highlight that negative stressors such as pressure to achieve target HbA1c levels according to guidelines, lifestyle considerations, behavior modifications, and fear of complications are factors that may lead to the increased frequency of mood disorders, attempted suicide, and psychiatric care in adults with diabetes.19, 26, 28, 30, 31

Autoimmune T1D may compromise brain development, as data suggest that DKA may cause subtle – yet frequent and persistent – brain injury.11, 13, 31

Children and adolescents with autoimmune T1D are more at risk for pathophysiological brain changes,19 and a single episode of moderate/severe DKA in young children at diagnosis is associated with lower cognitive scores and altered brain growth.13

Children with autoimmune T1D have been found to fare worse than their peers in terms of education and health outcomes, especially those who experience higher mean HbA1c.32

Adding the risk of brain injury – which may impair learning abilities and educational outcomes – to the physical burden and the persistently demanding self-management, it has been found that living with autoimmune T1D is associated with lower health-related quality of life, higher unemployment, and additional sick leave.33

Family Impact of a Child Receiving an Autoimmune T1D Diagnosis

Depending on the age of the person who develops autoimmune T1D, the quality of life of parents and other family members may also be negatively affected by the condition. Many parents of young children and adolescents who are diagnosed with autoimmune T1D experience increased psychological distress and share the burden of diabetes management.34

It is highlighted in the literature that caring for a young child with autoimmune T1D can be a relentless undertaking, which can have a detrimental impact on parents’ own well-being, relationships, personal choices, and everyday activities.35

The notion of Monopolization of Life explains how autoimmune T1D can be all-encompassing in parents’ lives and that parents may experience negative impact on their well-being, relationships, and finances due to varying degrees of worrying and feelings of needing to be vigilant in providing care.35

Further, parents’ reactions of shock from their child’s diagnosis, unresolved feelings of guilt, and psychological distress can negatively affect parents’ abilities to manage their child’s diabetes.36

The fear of complications that is found to contribute significantly to anxiety in parents of children with autoimmune T1D may become a vicious cycle where the higher the parental fear (especially of hypoglycemia), the worse child’s success rate in achieving blood glucose levels according to guidelines, and the lower the subjective wellbeing in parents.37

Research shows that mothers and fathers are impacted differently if their children are diagnosed with autoimmune T1D. Mothers are found to often carry a heavier burden than fathers, as family health care is predominantly considered a female task, despite trends toward shared parenting responsibilities.19, 35, 37-40

The observed inequality between parents of different genders may negatively impact mothers of newly diagnosed children with regards to their occupational situation. Mothers of diagnosed children may experience significant employment- and financial losses that can deteriorate their economic situation and mental health.38

Other research suggests that fathers gradually assume more responsibility for care and management of autoimmune T1D, and that the burden of care increases in fathers and decreases in mothers over the course of app. 12 months.39

A final aspect regarding how the burden of autoimmune T1D may impact entire families relates to the transitional period when a diagnosed person transitions from the pediatric to adult care setting.

Being diagnosed with autoimmune T1D in childhood or adolescence may interfere with normative developmental changes and interact with psychological and social factors.19

In addition, the shift to adult care may occur at a point in life that coincides with decreased adherence to diabetes-related management tasks, decreased clinic attendance, and increased risk-taking behaviors.41

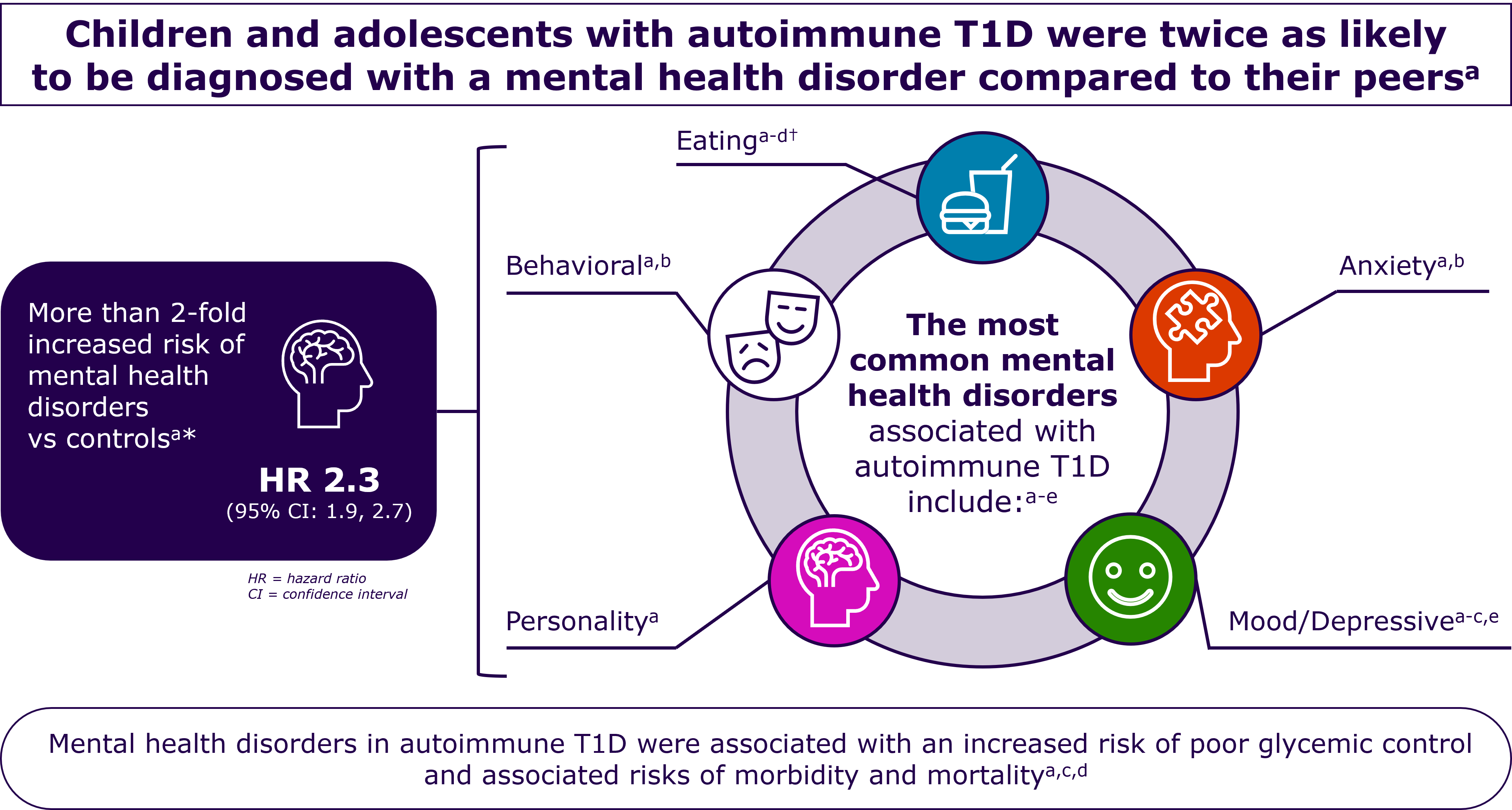

During this shift, youths and young adults with autoimmune T1D are at increased risk of psychiatric disorders and about twice as likely to be diagnosed with a psychiatric disorder (e.g. eating-, mood-, anxiety-, and behavior disorders) as peers without autoimmune T1D.19, 41

*Data shown are from 1302 children aged <16 years who were enrolled in the Western Australia Childhood Diabetes Database.

†In individuals with autoimmune T1D, in addition to anorexia nervosa or bulimia nervosa, insulin omission or restriction may be used as an additional means of weight control.d

a. Cooper MN et al (2017) Pediatric Diabetes,18(7),pp.599-606; b. Butwicka A, et al. (2015) Diabetes Care 38, 453-9. c. Dybdal D et al. (2018) Diabetologia, 61(4),pp.831-838; d. Hanlan ME, et al. Curr Diab Rep. 2013:10.1007/s11892-013-0418-4. e. Butwicka A, et al. (2016) Psychosomatics, 57(2),pp.185-93.

Can Early Detection of Diabetes-Specific Islet Autoantibodies Lessen the Burden of Autoimmune T1D?

It stands to reason that the burden of autoimmune T1D is both complex and persistent.

People affected by the condition face a myriad of challenges in learning how to achieve blood glucose levels according to guidelines and in minimizing the effects and complications associated with beta cells loss.

The steepness of the learning curve and the short- and long-term success in managing the condition might be determined by how people come to discover that they are living autoimmune T1D.2, 42

Studies that focus on early detection of individuals who are progressing through the pre-symptomatic Stages 1 and 2 of autoimmune T1D have found the potential benefits of early detection to be:

- Reduced risk of experiencing diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA) at the time of diagnosis, which is conventionally when an individual has progressed to Stage 3 autoimmune T1D where symptoms may onset and more severe complications may arise.16

- Improved health-related quality of life; higher degree of preparedness among children and their parents if a child is screened prior to being diagnosed at Stage 3; and lower parenting stress post-diagnosis compared to children diagnosed without screening.2

- Milder clinical presentation in children who participate in education and monitoring after early-stage diagnosis.42

Depending on the results, people who test positive for diabetes-specific islet autoantibodies (IAb+) may experience emotional reactions such as shock, grief, guilt, anger, depression, and anxiety, as those who are IAb+ discover that they have a higher risk of developing Stage 3 autoimmune T1D.2, 16, 43

Early detection studies such as BABYDIAB, TEDDY, Fr1da, and DiPiS highlight the psychological impact of islet autoantibody screening.16, 44, 45 One study has raised the discussion point that first-degree relatives (FDRs) show higher anxiety levels than non-FDRs up to 5 years after testing IAb+. This is potentially due to FDRs having firsthand experience with what it entails to manage of autoimmune T1D and thus having more accurate risk perception than parents from the general population.45

However, when it is related to anxiety or depression in parents whose children have tested IAb+, researchers agree that the psychological impact decreases over time.16, 44

Seemingly, early detection through testing for diabetes-specific islet autoantibodies presents a dilemma between the value of knowing the risk of developing autoimmune T1D versus the psychological impact of worrying about potential risks.

Researchers who have reviewed the same studies that have found that IAb+ tests may cause psychological challenges also point out that there are clear benefits to screening for autoimmune T1D, and that autoimmune T1D screening programs in the general population are emerging worldwide. The potential benefits from early detection through screening include: 2,16,42,46,47

- Knowledge that allows people to adjust to the diagnosis progressively and time to process and prepare for the prospect that oneself or a loved one will likely develop autoimmune T1D.

- Knowledge of the increased risk for developing autoimmune T1D, which likely decreases how surprised and overwhelmed people feel at potential symptom onset.

- Knowledge and skills (e.g. for metabolic monitoring), which may enable them to have lower rates of DKA and reduced HbA1c when progressing to stage 3 of autoimmune T1D.

- Higher degree of diabetes-specific quality of life across the first year following diagnosis.

The 1st Decision is about

who to screen

and how to screen

Sanofi is committed to providing a new understanding and perspective on Type 1 Diabetes. Join us!

-

El Malahi A et al. (2022) J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 18, 107(2), e570-e581, PMID-34534297

-

Smith LB et al. (2018) Pediatr Diabetes. 19(5) 1025-1033

-

Wolfsdorf et al. (2009) - Pediatric Diabetes, vol. 10(Suppl. 12) 118–133

-

Birkebaek NH et al. (2022) Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 10(11) 786‐794

-

Duca LM, et al. (2017) Diabetes Care. 40(9) 1249-1255

-

Glaser N et al. (2022) ISPAD clinical practice consensus guidelines, 23(7) 835-856

-

Jiang J et al. RCSB PDB-101 (online) https://pdb101.rcsb.org/global-health/diabetes-mellitus/monitoring/complications (Accessed 11 Nov 2024)

-

Rikos N, et al. (2022) NursRep. 12(3)564-573

-

Muñoz C, et al. (2019) Clin Diabetes. 37(3) 276-281

-

Harvard health https://www.health.harvard.edu/a_to_z/type-1-diabetes-mellitus-a-to-z (Accessed 11 Nov 2024)

-

Cameron FJ et al. (2014). Diabetes Care. 37(6) 1554-1562

-

Hammersen J et al. (2022) Pediatr Diabetes 22(3), pp.455-62

-

Aye T et al. (2019) Diabetes Care. 42(3), pp.443-9

-

DiMeglio LA, et al. (2018) Lancet. 391(10138) - 2449-2462

-

Nakhla M et al. (2018) CMAJ. 190(14)E416-E421

-

Phillip et al. (2024) ADA & EASD, Consensus Guidance, Vol 67, pp1731–1759

-

Mendez Y et al (2017) World J Diabetes 8 (2),pp. 40-44

-

Ghetti S et al. (2010) J Pediatr 156, pp.109-114

-

de Wit et al. (2022) Pediatr Diabetes, Dec 23(8)1373-1389

-

Kelly RC et al. (2023) Diabetic Medicine march 2024, Vol. 41, issue 3

-

Tack CJ et al. (2018) JMIR Diabetes Oct-Dec 3(4) e17

-

Digitale E, Scopeblog Stanford. https://scopeblog.stanford.edu/2014/05/08/new-research-keeps-diabetics-safer-during-sleep/ (Accessed 11 Nov 2024)

-

Gamarra E et al. (2023) J. Pers. Med. 13(2), 374. PMID-36836608

-

Chiavaroli L et al. (2021) BMJ. 4-374-n1651. PMID-34348965

-

Shah RB et al. (2016) Int. Jour. of Pharmaceutical Investigation, Vol. 6, Issue 1, pp.1-9

-

Barnard-Kelly KD et al. (2020). J Diabetes Sci Technol. 14(6)1010-1016

-

Fagherazzi G (2023) Diab Epidemiology and Management Vol.11,100140

-

Hendrieckx C et al. (2021) American Diabetes Association, 3rd Edition (U.S.)

-

Farooqi A et al.(2022) Primary Care Diabetes, Vol. 16, Issue 1,pp.1-10

-

Leslie RD et al. (2021), Diabetes Care 44, pp. 2449–2456

-

Butwicka A, et al. (2015) Diabetes Care 38, 453-9

-

Fleming M et al. (2019) Diabetes Care. 42(9), pp.1700-7

-

Nielsen HB et al. (2016) Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 121, pp.62-8

-

Wherrett DK et al. (2015) Diabetes Care 38, pp1975–85

-

Kimbell et al. (2021) BMC Pediatrics vol. 21, Article no. 160

-

Rankin D et al. (2014) Pediatric Diabetes, vol. 15, issue 8, pp543-610

-

Pate T et al. (2019) J Health Psychol Feb24(2), pp.209-218

-

Dehn-Hindenberg A et al. (2021) Diabetes Care. 44(12), pp.2656-63

-

Nieuwesteeg A et al. (2016) Diabetic Medicine June 2017, vol. 34, issue 6, pp741-867

-

Lindström C et al. (2017) J. of Pediatric Nursing 36,pp.149–156

-

Robinson M-E et al. (2021) Diabet Med. Jun 38(6) e14541

-

Hummel et al. (2023) Diabetologia, Vol. 66, pp. 1633–1642

-

Johnson SB et al. (2017) Diabetes Care 40, pp. 1167-1172

-

Raab J et al. (2016) BMJ Open 6-e011144

-

Melin J et al. (2020) Pediatr Diabetes 21(5),pp.878-889

-

Narendran P. (2018) Diabetologia. 62(1) 24-27

-

Besser R & Griffin K (2024) Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol,pp2213-8587(24)00238-9

Neem contact op

MAT-BE-2401070–v1.0–NOV2024