- Artikel

- Bron: Campus Sanofi

- 2 jul 2024

Time to Rethink T1D?

Type 1 Diabetes (T1D) is a progressive autoimmune disease with increasing incidence rate worldwide.1-4,10,19

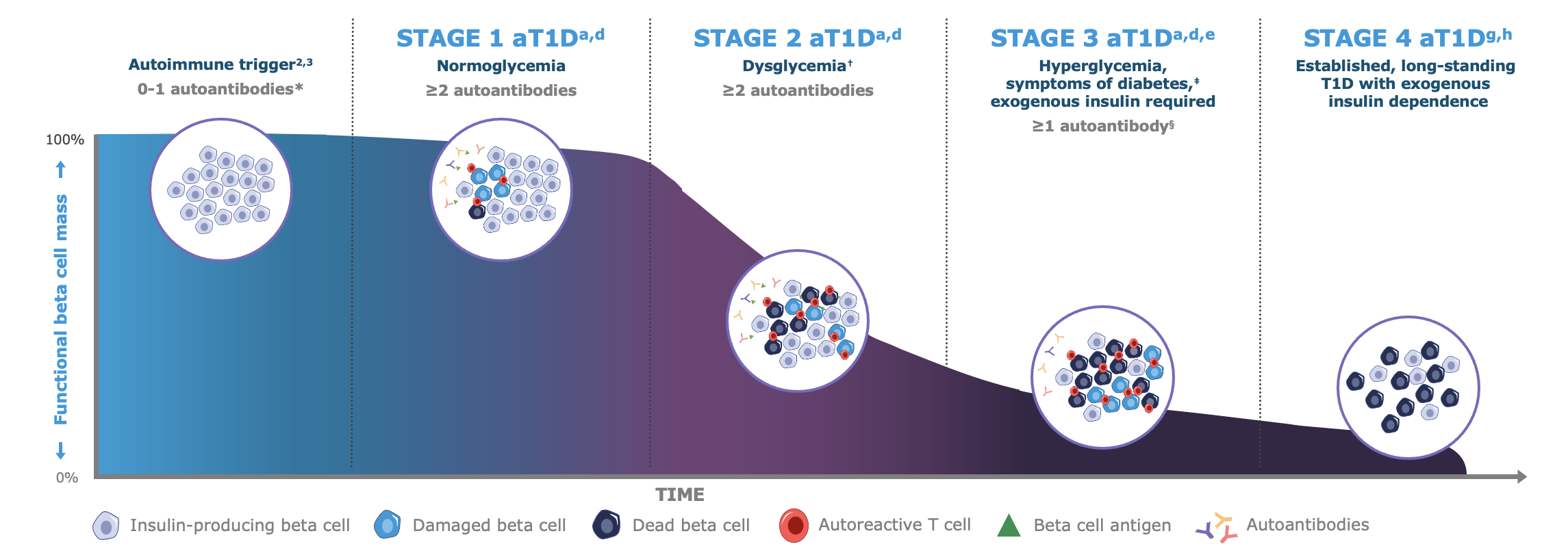

Autoimmune Type 1 Diabetes (autoimmune T1D) manifests in three progressive stages, and the onset of the condition begins months to years before the manifestation of clinical symptoms.2-4

Stages 1 and 2 of autoimmune T1D are pre-symptomatic, and in Stage 3, those who develop the condition may experience clinical manifestation of symptoms or even complications that require hospitalization.2-7

Many people only discover they have autoimmune T1D when the effects of the natural course of the condition have already become apparent.1 Many experience that being diagnosed with autoimmune T1D has a profound negative impact on the lives of the individual and their entire family.13,25-30

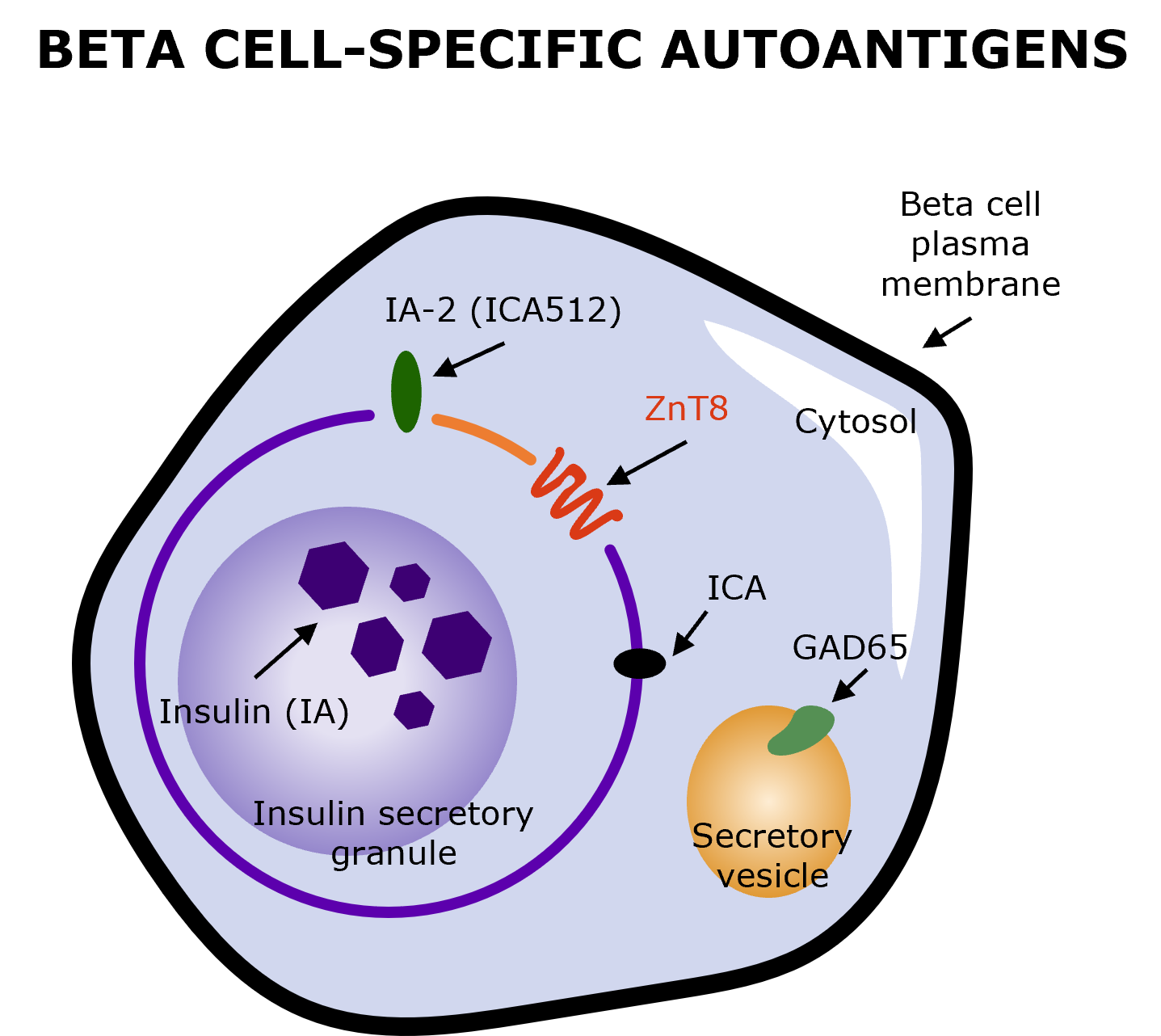

Even though there are no symptoms, autoimmune T1D is detectable in early stages, and detection entails simple blood sample-testing for consensus pancreatic islet autoantibodies (GAD-65, IA-2A, IAA, ZnT8A).2-4

* Autoantibodies to ≤1 beta cell autoantigen (insulin, glutamic acid decarboxylase [GAD65], islet antigen 2 [IA-2], or zinc transporter 8 [ZnT8]) are detected in patient serum.a †Fasting plasma glucose (FPG) of 100 to 125 mg/dL or 2-hour plasma glucose (PG) during oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) of 140 to 199 mg/dL, or A1C 5.7%-6.4% (39-47 mmol/mol) or ≥10% increase in A1C is observed.d ‡Common symptoms of T1D include polydipsia, polyuria, hunger, extreme fatigue, blurry vision, and weight loss.a,d §In some patients, autoantibodies may become absent in Stage 3 T1D.d

Note: Figure is an example for illustrative purposes, drawn up by Sanofi, based on ref. a-g:

a. Insel RA et al. Diabetes Care (2015) 38 1964–74 | b. van Belle TL et al. Physiole Rev 2011; 91: 79–118 | c. Jacobsen LM, et al. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2018 9,70 | d. American Diabetes Association Professional Practice Committee. Diabetes Care 2022; 45 (Suppl. S1): S17–S38 | e. McCall AL & Farhy LS. Minerva Endocrinol 2013; 38: 145–63 | f. Mayo Clinic. Diabetes symptoms when diabetes symptoms are a concern https //www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/diabetes/in-depth/diabetes-symptoms/art-20044248 (Accessed 15 Sep. 2025) | g. Sims EK, et al. (2022) Diabetes 71(4) 610-623 | h. Besser REJ, et al. (2022) Pediatr Diabetes. 23(8) 1175-1187.

The Cause and Risk of Progression of Autoimmune T1D

The exact processes that lead to the development of autoimmune T1D are not yet fully understood, and the condition is characterized by varying, individual rates of progression and possibly different underlying causes.14,15,33

Genetics may play a role in people developing the condition, and genetically susceptible individuals (e.g. those with first degree relatives who have been diagnosed with autoimmune T1D) are considered part of the risk population.10,15

The development of autoimmune T1D may also be triggered as a result of environmental triggers such as a viral infection (e.g. SARS-CoV)3, changes in diet, or metabolic stressors.15 Early childhood viral infections probably promote the occurrence of autoimmune T1D.14,19

The initiation of the autoimmune disease likely occurs already during the first two years of life.5,16,31 Individuals who develop pre-symptomatic Stage 2 autoimmune T1D have a 75% risk of progressing to Stage 3 within five years (i.e. potential symptom onset and need of insulin treatment). The lifetime risk of progressing to Stage 3 autoimmune T1D is nearly 100%.3,32

People who develop autoimmune T1D, but who go undetected until they enter Stage 3, may experience initial symptoms such as:17,18

- Feeling extremely thirsty and drinking excessive amounts of fluid (polydipsia).

- Excessive and often urination (polyuria).

- Losing weight – with no loss of appetite or without attempting to lose weight.

- Being much more tired or feeling weaker than usual (fatigue).

- Having blurry vision or seeing double.

Additional common symptoms that people may experience in Stage 3 of autoimmune T1D are confusion, nausea, and vomiting. The initial symptoms of Stage 3 autoimmune T1D highlighted here may be caused both by dehydration and by the condition called diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA).17

The Complex Burden of Autoimmune T1D

Autoimmune Type 1 Diabetes often has severe impact on those who develop the condition – both physically and mentally. Both the physical and mental effects of autoimmune T1D can be acute and long-term, and both types of effects can impact directly on the affected individual and on their family (mainly parent-caregivers and siblings), depending on the age of the individual who is diagnosed.

Receiving an autoimmune T1D diagnosis can be very difficult for entire families with both children and parents exhibiting psychological symptoms such as distress, stress, anxiety, and depression.25-30 Some parents may also have feelings of guilt about their child’s condition, evidently more so, if the child was diagnosed as a consequence of having experienced more severe symptoms such as diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA).29,30

Children with new onset of autoimmune T1D frequently present with DKA. Frequencies range from approximately 15% to 70% in Europe and North America.20 Across Northern Europe, approximately 30% of children and adolescents (aged 6 months to <18 years) are diagnosed because of a DKA event.21

DKA at diagnosis of autoimmune T1D in children predicts poor long-term glycemic control, independent of demographic and socioeconomic factors.22

In the long-term, deviation from blood glucose levels according to guidelines may lead to other serious and/or potentially life-threatening complications such as:17-24

- Eye damage (retinopathy) by damage to the tiny blood vessels of the retina caused by high blood sugar

- Nerve damage (neuropathy) as high blood sugar can damage nerves, leading to pain or numbness of the affected body part

- Foot complications such as sores and blisters caused by numbness from peripheral neuropathy

- Kidney disease (nephropathy) as high blood sugar can damage the kidneys, potentially leading to kidney failure

- Increased risk of heart- and artery disease such as strokes related to poor circulation

- Sub-clinical brain alterations and detrimental neurocognitive outcomes

- Increased morbidity and mortality

In terms of mental impact of autoimmune T1D, the wide array of potential acute and chronic complications causes autoimmune T1D diagnoses to often be associated with strong feelings of grief, sorrow, and anxiety.13,25,29,30

The negative psychological impact of being diagnosed with autoimmune T1D likely differs depending on whether the affected individuals receive news of their condition through diagnosis based on clinical symptoms (incl. diabetic ketoacidosis) or through screening for autoantibodies. When it comes to the negative impact of receiving an autoimmune T1D diagnosis, people diagnosed through screening and monitoring compares favorably to those diagnosed with clinical symptoms.13,34

Those who develop autoimmune T1D will need to adapt their lives to include numerous health management actions such as blood glucose-monitoring, insulin injections, measured diet and exercise regimens, and regular consultations with healthcare professionals. It has been estimated that life with autoimmune T1D requires the individual to consider upwards of 180 health-related decisions per day.27,28

For those who are diagnosed as a consequence of symptoms manifestation in Stage 3 – or after experiencing a DKA event – one can imagine how steep the learning curve is for managing their condition. When considering the potential consequences of hypoglycemic- and hyperglycemic episodes – as well as what it requires for newly diagnosed people to steer clear of both – one can imagine the psychological burden of managing autoimmune T1D.

For people with autoimmune T1D to become proficient at self-monitoring and self-management requires extensive education and substantial efforts – both of which may require longer periods of time.13,27 Arguably, more time is needed if the individual diagnosed with autoimmune T1D is a child or adolescent who is reliant on parents and other caregivers for monitoring and management.

Several studies point out that screening for autoantibodies to discover pre-symptomatic autoimmune T1D can provide those at risk of testing positive and their families with additional time to educate themselves and prepare for a life with chronic autoimmune T1D.5,13,34

Autoimmune Type 1 Diabetes Can Be Detected Early

Despite the absence of symptoms in the early stages of the condition, the autoimmune disease can still be detected in Stage 1 and stage 2.2-4

Early stages of autoimmune T1D are detected by the presence of diabetes-specific autoantibodies.9,14 Autoantibody-testing involves a simple blood test for consensus pancreatic islet autoantibodies (GAD-65, IA-2A, IAA, ZnT8A), with potential repetitive testing based on the result.2,9,14

Illustration produced by Sanofi with data from Arvan P, et al. (2012) (Fig. 2)9

The aim of early detection is to prevent diabetic ketoacidosis at the time of diagnosis and at the same time to determine the best time to start insulin therapy.3,5

Early detection gives those affected the opportunity to familiarize themselves with the effects that their diagnosis may have on their daily lives – before symptoms may manifest. Early detection also provides opportunities for the affected and healthcare professionals to structure education and training, which may enable gentle adjustment to life with autoimmune T1D.13,15,34

Sanofi is committed to providing a new understanding and perspective on Type 1 Diabetes. Join us!

The 1st Decision is about

who to screen

and how to screen

Neem contact op

Referenties

-

Gregory GA et al. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol (2022) 10, 741-60

-

ElSayed NA et al. Diabetes Care (2023) 46 (Suppl. 1) S19–S40

-

Insel RA et al. Diabetes Care (2015) 38 1964–74

-

Jacobsen LM, et al. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2018 9,70

-

Phillip et al. (2024) ADA & EASD, Consensus Guidelines

-

Birkebaek NH et al. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2022 10(11) 786‐794

-

Seshasai SRK et al. (2011), N Engl J Med. 364(9) 829-841

-

Narendran P. Diabetologia. 2019 62(1) 24-27

-

Arvan P, et al. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2012 2(8) a007658

-

van Belle TL, et al. Physiol Rev. 2011;91(1):79-118

-

McCall AL, Farhy LS. (2013) Minerva Endocrinol. 38(2) 145-163

-

Mayo Clinic. Diabetes symptoms: when diabetes symptoms are a concern: https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/diabetes/in-depth/diabetes-symptoms/art-20044248 (Accessed 30 Apr. 2024)

-

Smith LB, et al. Pediatr Diabetes. 2018 19(5) 1025-1033

-

Regnell SER & Lenmark Å (2017) Diabetologia, Vol. 60, pages 1370–1381

-

Joglekar MV et al. (2024) Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. May 23 S2213-8587(24)00103-7

-

Ziegler AG & Bonifacio E. Diabetologia 2012; 55: 1937–43

-

Harvard health https://www.health.harvard.edu/a_to_z/type-1-diabetes-mellitus-a-to-z (Accessed 12 June, 2024)

-

Mayo Clinic. https //www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/diabetes/in-depth/diabetes-symptoms/art-20044248 (Accessed 12 June, 2024)

-

Muñoz C, et al. Clin Diabetes. 2019;37(3):276-281

-

Wolfsdorf et al. (2009) - Pediatric Diabetes, vol. 10(Suppl. 12) 118–133

-

Birkebaek NH et al. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2022;10(11):786‐794

-

Duca LM, et al. Diabetes Care. 2017;40(9):1249-1255

-

Glaser N, et al. (2022) ISPAD clinical practice consensus guidelines, 23(7) 835-856.

-

Jiang J, Dutta S. Diabetes Mellitus Complications. RCSB PDB-101 https //pdb101.rcsb.org/global-health/diabetes-mellitus/monitoring/complications (Accessed 12 June, 2024)

-

Rikos N, et al. (2022) NursRep. 12(3)564-573

-

Eilander MMA et al., (2015) BMC Pediatrics Vol. 15, article number 82

-

Tack CJ et al., (2018) JMIR Diabetes Oct-Dec 3(4) e17

-

Erin Digitale Scopeblog Stanford. [2017-11-29] http://scopeblog.stanford.edu/2014/05/08/new-research-keeps-diabetics-safer-during-sleep/ (Accessed 12 June, 2024)

-

Rankin D et al. (2014) - Pediatric Diabetes, vol. 15, issue 8, pp543-610

-

Nieuwesteeg A et al., (2016) Diabetic Medicine June 2017, vol. 34, issue 6, pp741-867

-

Katsarou A et al. (2017) Nat Rev Dis Primers. A1063 17016

-

Peters A. (2021) Journal Fam Pract. 70(6S) S47-S52

-

Rodriguez-Calvo T et al. (2021) Front Immunol vol. 12 article 667989

-

Hummel et al. (2023) Diabetologia, Vol. 66, pp. 1633–1642

MAT-NL-2400454 – v1.0 – 06/2024