- Articolo

- Fonte: Campus Sanofi

- 24 set 2024

Il ruolo dell'infiammazione di tipo 2

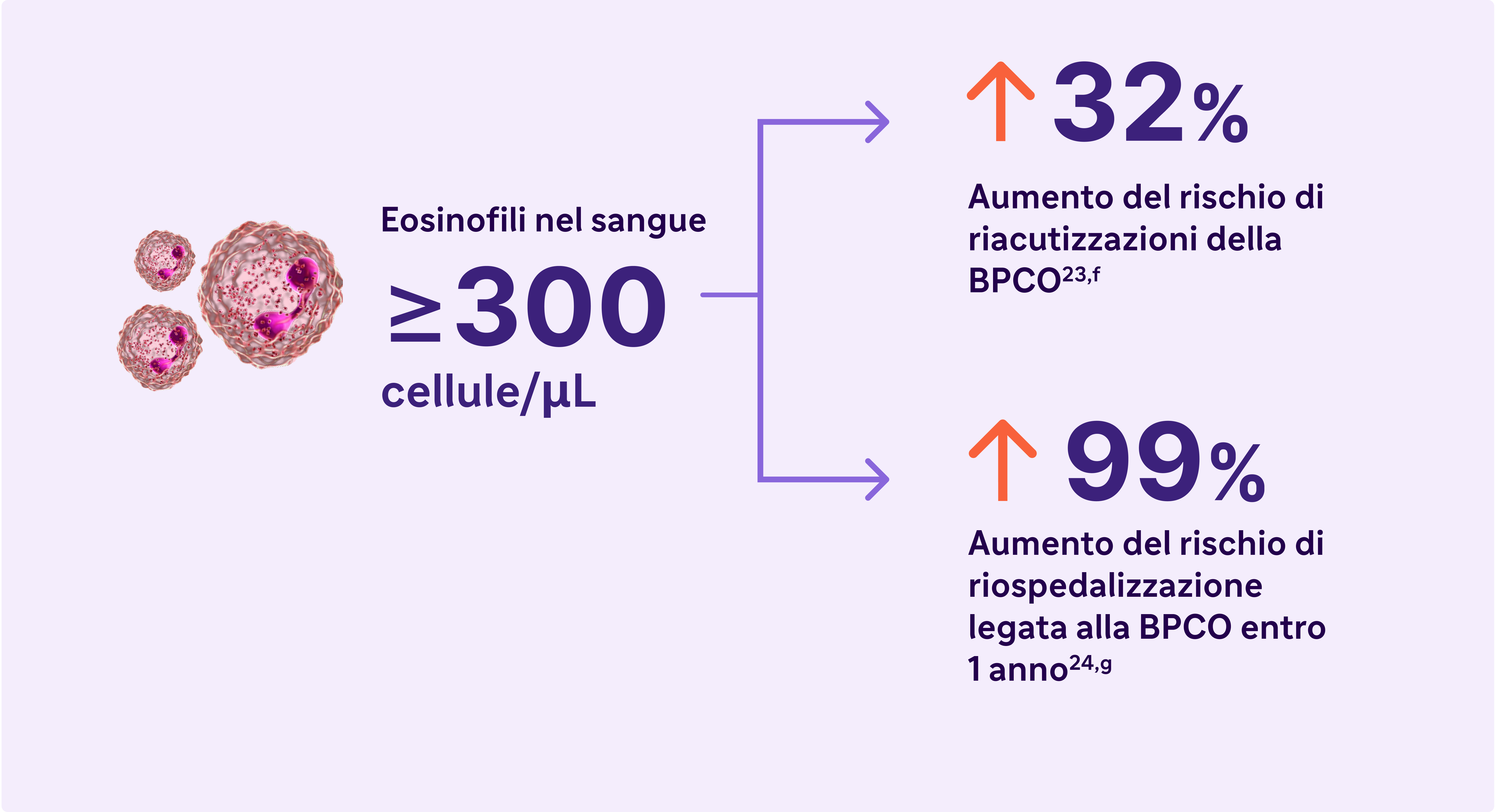

L'infiammazione di Tipo 2 può aumentare il rischio di riacutizzazioni e di compromissione della funzionalità polmonare nella BPCO.23,24

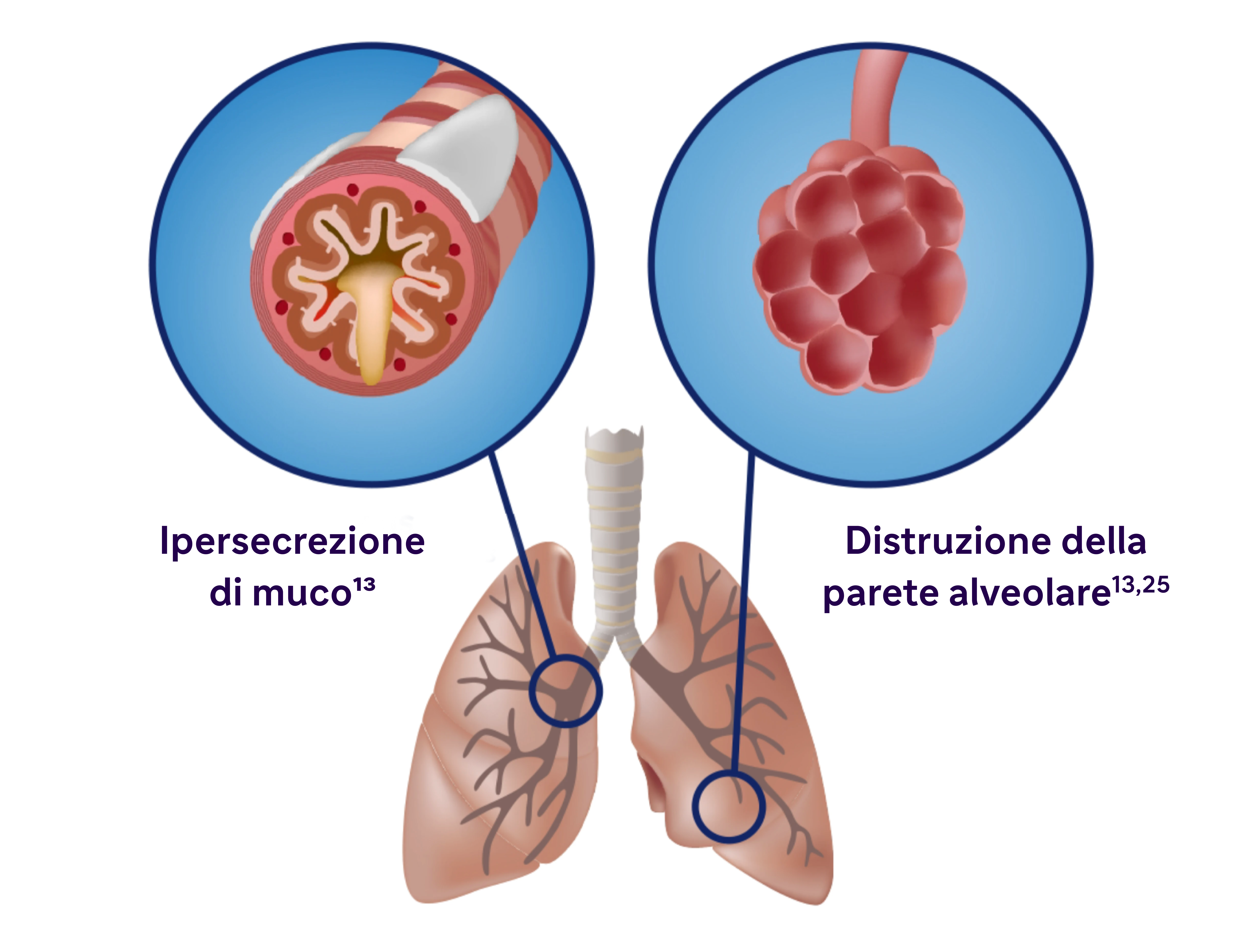

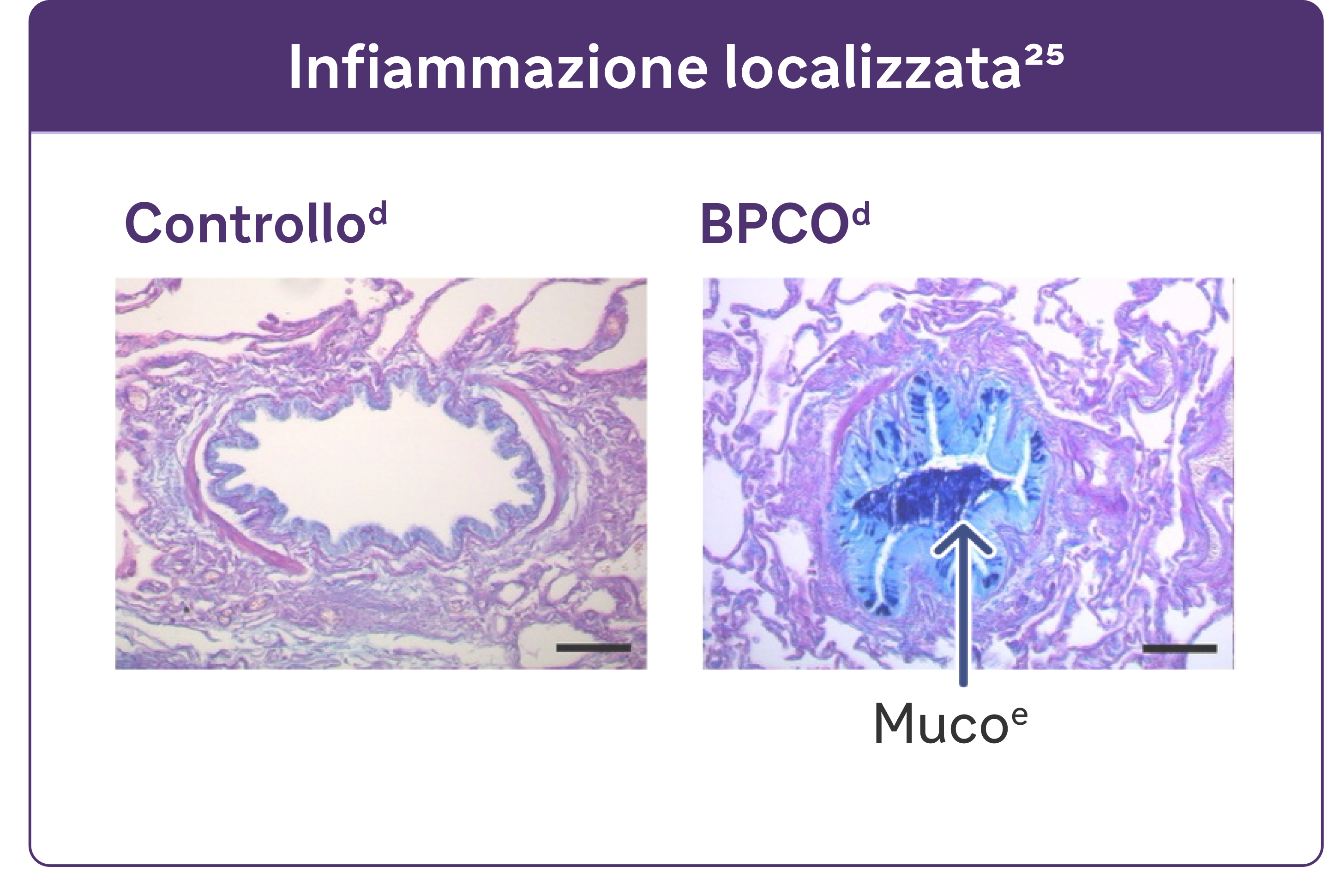

La BPCO è caratterizzata da produzione di muco, ostruzione delle vie aeree e tosse.13

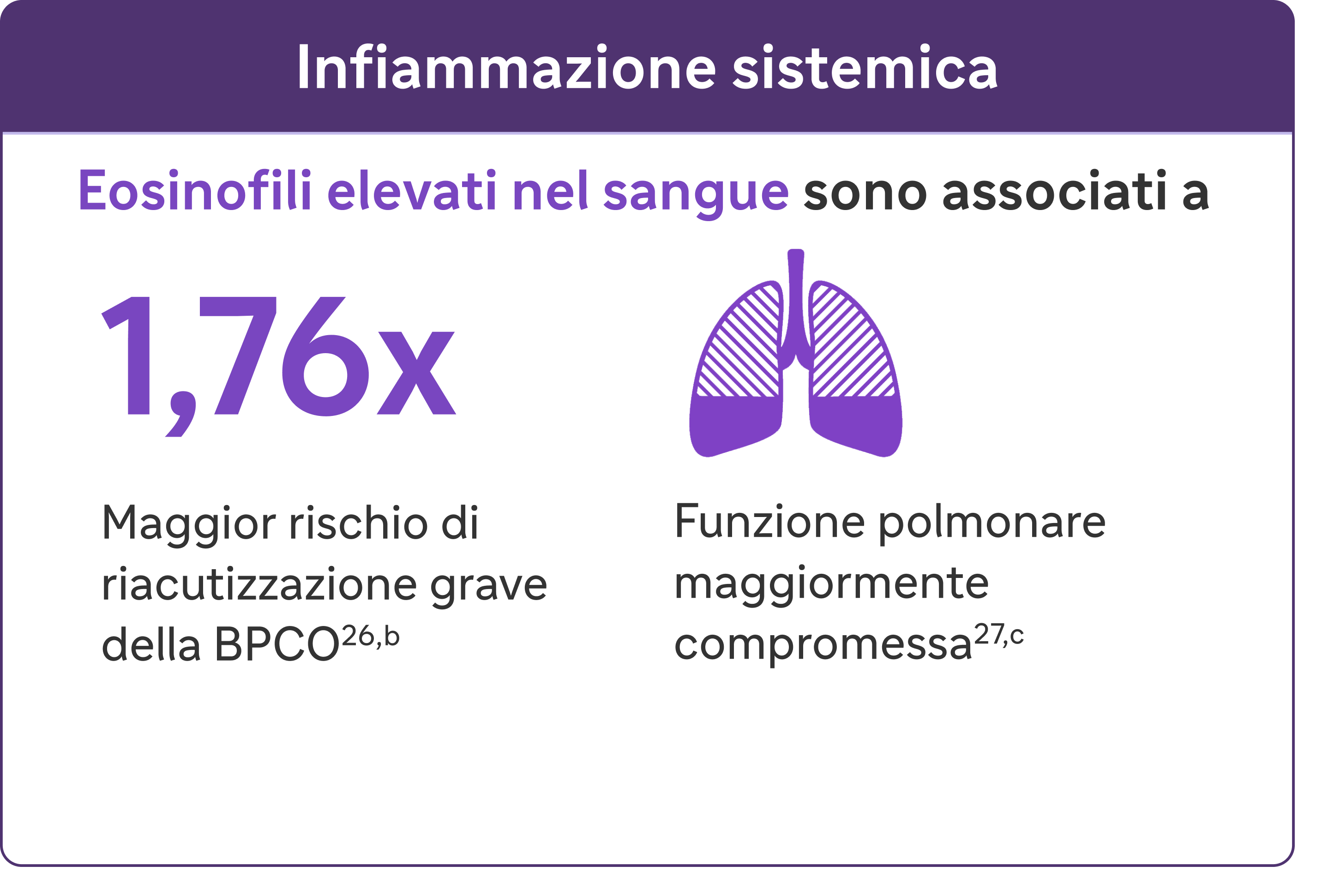

L'infiammazione si manifesta a livello sistemico e locale

- L'infiammazione cronica provoca cambiamenti strutturali, tra cui il restringimento delle vie aeree e la riduzione dell'elasticità dei polmoni.13

- Alcuni studi hanno individuato una correlazione tra l'infiammazione e l'ipersecrezione di muco in patologie respiratorie come la BPCO.25

Ascolta il professor Nicola Hanania: "Non la consideriamo più come una malattia uguale per tutti".

1:36 minuti

Nicola Hanania è professore di medicina, direttore del reparto di terapia critica polmonare e medicina del sonno presso l'ospedale Ben Taub di Houston, Texas, e direttore del Centro di ricerca clinica sulle vie aeree, ACRC, presso il Bear College of Medicine.

.webp)

Ascoltate l'intero episodio del podcast suSito web EMJ

Sponsorizzato da Sanofi e Regeneron, in collaborazione con EMJ.

Penso che il nostro approccio a questa malattia sia cambiato, ora che sappiamo che ha molteplici fenotipi, ma non solo, abbiamo anche identificato molteplici meccanismi della malattia, quindi non la consideriamo più un'unica malattia uguale per tutti. E' pertanto molto importante per il medico scavare a fondo nella storia del paziente per identificare questi fenotipi: che si tratti di un fenotipo con frequente riacutizzazioni, di un fenotipo bronchitico cronico, di un fenotipo principalmente enfisematoso. Ora utilizziamo biomarcatori come gli eosinofili nel sangue e forse avremo altro ancora in arrivo in futuro, come biomarcatori radiologici, che potrebbero aiutarci a suddividere questo gruppo di pazienti in modo da poter adottare un approccio sempre più personalizzato. Penso che questo sia un momento molto emozionante per la BPCO, siamo passati da questo approccio di tipo "blue-bloater pink puffer" ad avere ora, come detto, sottotipi o fenotipi multipli e includendo l'identificazione di diversi meccanismi in modo da avere un approccio più mirato a questa malattia. Spero che questo aiuterà a migliorare i risultati in futuro, ovviamente. Questo è l'obiettivo principale, "spostare" quel rischio aumentato di mortalità che abbiamo visto nella BPCO; mentre con altre malattie abbiamo ottenuto molti risultati, nella BPCO, sfortunatamente, non abbiamo spostato molto questo aspetto, quindi penso che tutti quanti oggi speriamo, con questi nuovi approcci, di poter migliorare i risultati.

Cerca una conta di eosinofili elevati nel sangue (>300 cellule/μL) - un biomarcatore dell'infiammazione di tipo 2 nella BPCO.13

Gli eosinofili elevati nella BPCO sono un tratto curabile e un marker dell'infiammazione di tipo 213

Le raccomandazioni GOLD 2024 riconoscono livelli elevati di EOS nel sangue come biomarcatore clinicamente utilizzato per identificare la BPCO con infiammazione di tipo 2.

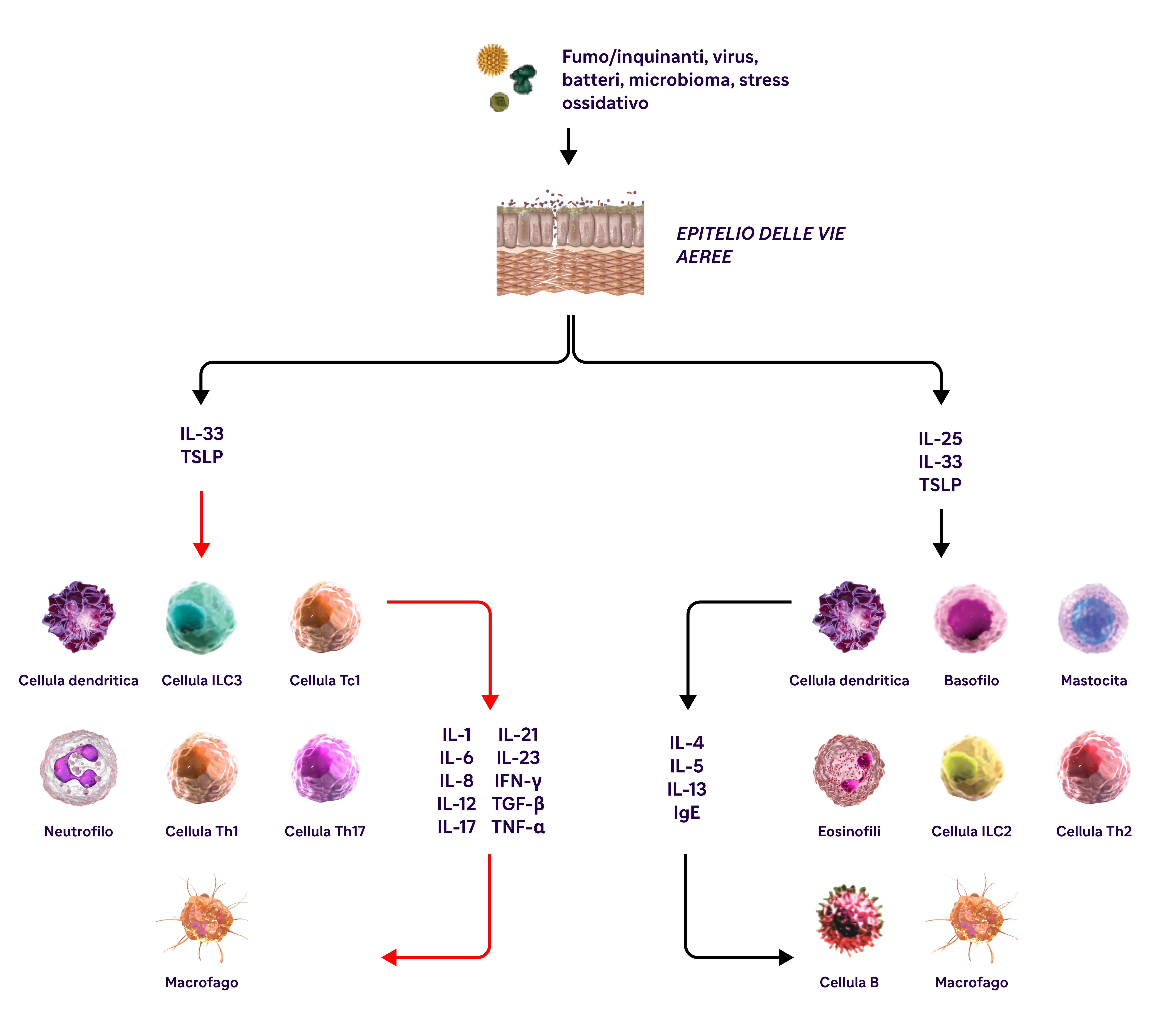

L'infiammazione di tipo 2 nella BPCO può coinvolgere più vie di trasduzione del segnale, citochine e cellule infiammatorie.28-33

IL-4, IL-13 e IL-5 sono citochine di tipo 2 coinvolte nella BPCO.

aBasato sui risultati di 5 studi condotti su pazienti con BPCO senza asma. I livelli di eosinofili utilizzati per definire l'infiammazione di tipo 2 variavano da ≥300 cellule/μL a ≥340 cellule/μL (sangue), ≥2% nell'espettorato indotto o 3% nel sangue periferico. Le percentuali di pazienti con infiammazione di tipo 2 variavano dal 12,3% al ~40%.23,24

bUna riacutizzazione grave è stata definita come un'ospedalizzazione dovuta alla BPCO. Le esacerbazioni dovevano essere distanziate di almeno 4 settimane per essere considerate esacerbazioni separate.27

cIn una coorte di pazienti con EOS >200 cellule/μL.26

dRiprodotto su autorizzazione dell'American Thoracic Society. Fritzsching B et al. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2015;191(8):902-91325

eColorazione PAS in blu di alcian del muco nelle cellule epiteliali delle vie aeree.25

fRisultati di uno studio osservazionale su 1553 pazienti con BPCO di grado 2-4 alla spirometria GOLD (rapporto FEV1/FVC postbroncodilatatore <0,7, con FEV >80% predetto)23

gRisultati di uno studio osservazionale di 1 anno su 479 pazienti con BPCO, 173 dei quali avevano livelli di eosinofili nel sangue ≥200 cellule/μL e/o ≥2% della conta totale dei globuli bianchi.24

BPCO, broncopneumopatia cronica ostruttiva; EOS, eosinofili; FEV1, volume espiratorio forzato in 1 secondo; FVC, capacità vitale forzata; GOLD, Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease; IFN-y, interferone-gamma; ILC2, cellule linfoidi innate di tipo 2; MUC5AC, mucina 5AC; PAS, periodic acid-Schiff; TNF-a, fattore di necrosi tumorale alfa; TSLP, linfopoietina timica stromale.

Bibliografia

1. Halpin DMG, Dransfield MT, Han MK, et al. The effect of exacerbation history on outcomes in the IMPACT trial. Eur Respir J. 2020;55:1901921. doi:10.1183/13993003.01921-2019

2. Suissa S, Dell’Anniello S, Ernst P. Long-term natural history of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: severe exacerbations and mortality. Thorax. 2012;67(11):957-963.

3. Halpin DMG, Decramer M, Celli BR, Mueller A, Metzdorf N, Tashkin DP. Effect of a single exacerbation on decline in lung function in COPD. Respir Med. 2017;128:85-91.

4. Cosio Piqueras MG, Cosio MG. Disease of the airways in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Eur Respir J. 2001;18(suppl 34):41s-49s.

5. Tajti G, Gesztelyi R, Pak K, et al. Positive correlation of airway resistance and serum asymmetric dimethylarginine level in COPD patients with systemic markers of low-grade inflammation. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2017;12:873-884.

6. Higham A, Quinn AM, Cançado JED, Singh D. The pathology of small airways disease in COPD: historical aspects and future directions. Respir Res. 2019;20(1):49. doi:10.1186/s12931-019-1017-y

7. O’Donnell DE, Parker CM. COPD exacerbations. 3: Pathophysiology. Thorax. 200661(4):354-361.

8. Calverley PMA. Respiratory failure in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Eur Respir J. 2003;22:26s-30s.

9. Roussos C, Koutsoukou A. Respiratory failure. Eur Respir J. 2003;22(suppl 47):3s-14s.

10. Aghapour M, Raee P, Moghaddam SJ, Hiemstra PS, Heijink IH. Airway epithelial barrier dysfunction in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: role of cigarette smoke exposure. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2018;58(2):157-169.

11. Brightling CE, Saha S, Hollins F. Interleukin-13: prospects for new treatment. Clin Exp Allergy. 2010;40(1):42-49.

12. Barberà JA, Peinado VI, Santos S. Pulmonary hypertension in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Eur Respir J. 2003;21(5):892-905.

13. Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease. Global strategy for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (2024 report). Accessed [February 9, 2024]. https://goldcopd.org/2024-gold-report-2/

14. Jones PW. St George’s Respiratory Questionnaire: MCID. COPD. 2005 Mar;2(1):75-79.

15. Jones P. St George’s Respiratory Questionnaire Manual. [Version 2.4, March 2022]. Accessed [February 9, 2024]. https://www.sgul.ac.uk/research/research-operations/research-administration/st-georges-respiratory-questionnaire/docs/SGRQ-Manual-March-2022.pdf

16. Evidera website. EXACT and E-RS:COPD content. Accessed [February 9, 2024]. https://www.evidera.com/what-we-do/patient-centered-research/coa-instrument-management-services/exact-program/ exact-content/

17. Leidy NK, Bushnell DM, Thach C, Hache C, Gutzwiller FS. Interpreting Evaluating Respiratory Symptoms in COPD diary scores in clinical trials: terminology, methods, and recommendations. Chronic Obstr Pulm Dis. 2022;9(4):576-590.

18. Oshagbemi OA, Franssen FME, van Kraaij S, et al. Blood eosinophil counts, withdrawal of inhaled corticosteroids and risk of COPD exacerbations and mortality in the clinical practice research datalink (CPRD). COPD. 2019;16(2):152-159.

19. Casanova C, Celli BR, de-Torres JP, et al. Prevalence of persistent blood eosinophilia: relation to outcomes in patients with COPD. Eur Respir J. 2017;50:1701162. doi:10.1183/13993003.01162-2017

20. Singh D, Kolsum U, Brightling CE, Locantore N, Agusti A, Tal-Singer R; ECLIPSE investigators. Eosinophilic inflammation in COPD: prevalence and clinical characteristics. Eur Respir J. 2014;44(6):1697-1700.

21. Bafadhel M, McKenna S, Terry S, et al. Acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: identification of biologic clusters and their biomarkers. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;184(6):662-671.

22. Oshagbemi OA, Burden AM, Braeken DCW, et al. Stability of blood eosinophils in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and in control subjects, and the impact of sex, age, smoking, and baseline counts. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2017;195(10):1402-1404.

23. Yun JH, Lamb A, Chase R, et al; COPDGene and ECLIPSE Investigators. Blood eosinophil count thresholds and exacerbations in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2018;141(6):2037-2047.e10. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2018.04.010

24. Bélanger M, Couillard S, Courteau J, et al. Eosinophil counts in first COPD hospitalizations: a comparison of health service utilization. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2018;13:3045-3054.

25. Fritzsching B, Zhou-Suckow Z, Trojanek JB, et al. Hypoxic epithelial necrosis triggers neutrophilic inflammation via IL-1 receptor signaling in cystic fibrosis lung disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2015;191(8):902-913.

26. Vedel-Krogh S, Nielsen SF, Lange P, Vestbo J, Nordestgaard BG. Blood eosinophils and exacerbations in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. The Copenhagen General Population Study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2016;193(9):965-974.

27. George L, Taylor AR, Esteve- Codina A, et al; U-BIOPRED and the EvA study teams. Blood eosinophil count and airway epithelial transcriptome relationships in COPD versus asthma. Allergy. 2020;75(2):370-380.

28. Yousuf A, Ibrahim W, Greening NJ, Brightling CE. T2 biologics for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2019;7(5):1406-1416.

29. Barnes PJ. Inflammatory endotypes in COPD. Allergy. 2019;74(7):1249-1256.

30. Oishi K, Matsunaga K, Shirai T, Hirai K, Gon Y. Role of type 2 inflammatory biomarkers in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J Clin Med. 2020;9(8):2670. doi:10.3390/jcm9082670

31. Gabryelska A, Kuna P, Antczak A, Białasiewicz P, Panek M. IL-33 mediated inflammation in chronic respiratory diseases—understanding the role of the member of IL-1 superfamily. Front Immunol. 2019;10:692. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2019.00692

32. Allinne J, Scott G, Lim WK, et al. IL-33 blockade affects mediators of persistence and exacerbation in a model of chronic airway inflammation. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2019;144(6):1624-1637.e10.

33. Calderon AA, Dimond C, Choy DF, et al. Targeting interleukin-33 and thymic stromal lymphopoietin pathways for novel pulmonary therapeutics in asthma and COPD. Eur Respir Rev. 2023;32(167):220144. doi:10.1183/16000617.0144-2022

34. Gandhi NA, Bennett BL, Graham NMH, Pirozzi G, Stahl N, Yancopoulos D. Targeting key proximal drivers of type 2 inflammation in disease. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2016;15(1):35-50.

35. Rosenberg HF, Phipps S, Foster PS. Eosinophil trafficking in allergy and asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2007;119(6):1303-1310.

36. Doyle AD, Mukherjee M, LeSuer WE, et al. Eosinophil-derived IL-13 promotes emphysema. Eur Respir J. 2019;53(5):1801291. doi:10.1183/13993003.01291-2018

37. Barnes PJ. Inflammatory mechanisms in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2016;138(1):16-27.

38. Defrance T, Carayon P, Billian G, et al. Interleukin 13 is a B cell stimulating factor. J Exp Med. 1994;179(1):135-143.

39. Yanagihara Y, Ikizawa K, Kajiwara K, Koshio T, Basaki Y, Akiyama K. Functional significance of IL-4 receptor on B cells in IL-4– induced human IgE production. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1995;96(6 pt 2):1145-1151.

40. Gandhi NA, Pirozzi G, Graham NMH. Commonality of the IL-4/IL-13 pathway in atopic diseases. Expert Rev Clin Immunol. 2017;13(5):425-437.

41. Kaur D, Hollins F, Woodman L, et al. Mast cells express IL-13Rα1: IL-13 promotes human lung mast cell proliferation and FcεRI expression. Allergy. 2006;61(9):1047-1053.

42. Saatian B, Rezaee F, Desando S, et al. Interleukin-4 and interleukin-13 cause barrier dysfunction in human epithelial cells. Tissue Barriers. 2013;1(2):e24333. doi:10.4161/tisb.24333

43. Zheng T, Zhu Z, Wang Z, et al. Inducible targeting of IL-13 to the adult lung causes matrix metalloproteinase– and cathepsin-dependent emphysema. J Clin Invest. 2000;106(9):1081-1093.

44. Garudadri S, Woodruff PG. Targeting chronic obstructive pulmonary disease phenotypes, endotypes, and biomarkers. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2018;15(suppl 4):S234-S238.

45. Alevy YG, Patel AC, Romero AG, et al. IL-13–induced airway mucus production is attenuated by MAPK13 inhibition. J Clin Invest. 2012;122(12):4555-4568.

46. Singanayagam A, Footitt J, Marczynski M, et al. Airway mucins promote immunopathology in virus-exacerbated chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J Clin Invest. 2022;132(8):e12901. doi:10.1172/JCI120901

47. Zhu Z, Homer RJ, Wang Z, et al. Pulmonary expression of interleukin-13 causes inflammation, mucus hypersecretion, subepithelial fibrosis, physiologic abnormalities, and eotaxin production. J Clin Invest. 1999;103(6):779-788.

48. Cooper PR, Poll CT, Barnes PJ, Sturton RG. Involvement of IL-13 in tobacco smoke-induced changes in the structure and function of rat intrapulmonary airways. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2010;43(2):220-226.

49. Arora S, Dev K, Agarwal B, Das P, Syed MA. Macrophages: their role, activation, and polarization in pulmonary diseases. Immunobiology. 2018;223(4-5):383-396.

50. He S, Xie L, Lu J, Sun S. Characteristics and potential role of M2 macrophages in COPD. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2017;12:3029-3039.

51. Wang X, Xu C, Ji J, et al. IL-4/IL-13 upregulates Sonic hedgehog expression to induce allergic airway epithelial remodeling. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2020;318(5):L888-L899.

52. Linden D, Guo-Parke H, Coyle PV, et al. Respiratory viral infection: a potential “missing link” in the pathogenesis of COPD. Eur Respir Rev. 2019;28(151):180063. doi:10.1183/16000617.0063-2018

53. Wang Z, Bafadhel M, Haldar K, et al. Lung microbiome dynamics in COPD exacerbations. Eur Respir J. 2016;47(4):1082-1092.

Codice deposito aziendale: MAT-IT-2402481