- Article

- Source : Campus Sanofi

- 10 sept. 2024

Rôle de l'inflammation de type 2

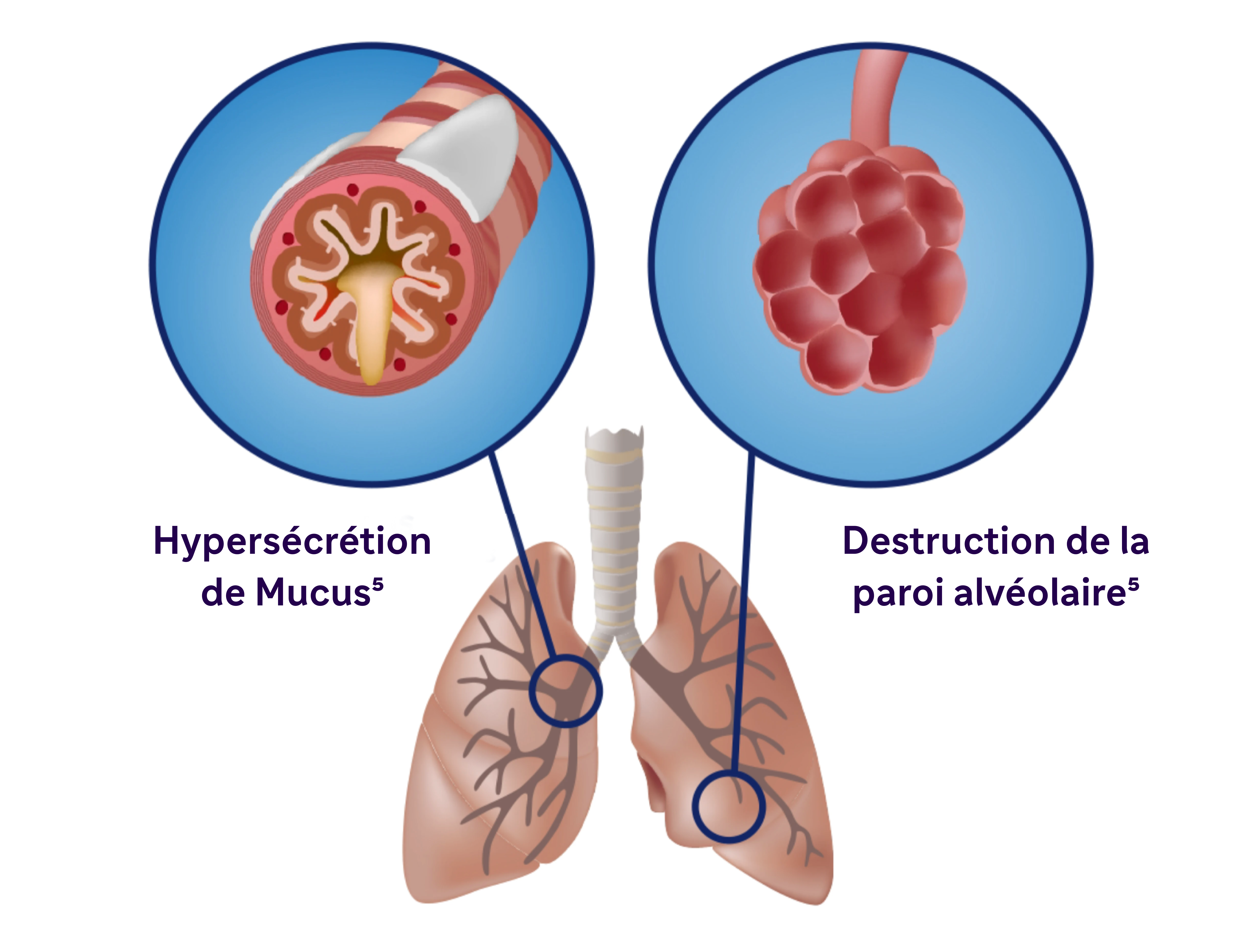

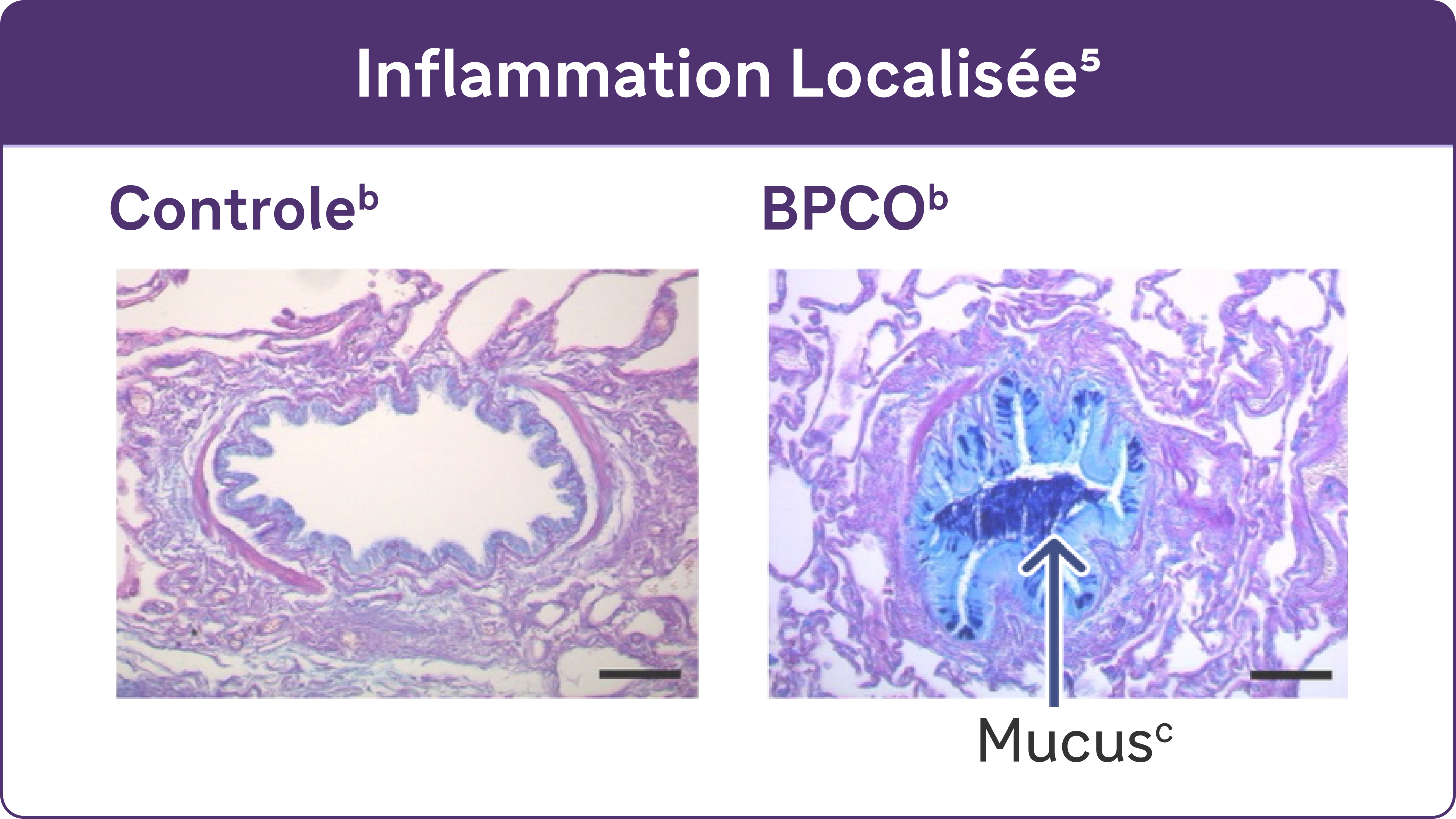

L’inflammation de type 2 peut aggraver les symptômes de la BPCO5

La BPCO se caractérise notamment par une production de mucus, une obstruction des voies respiratoires et de la toux5

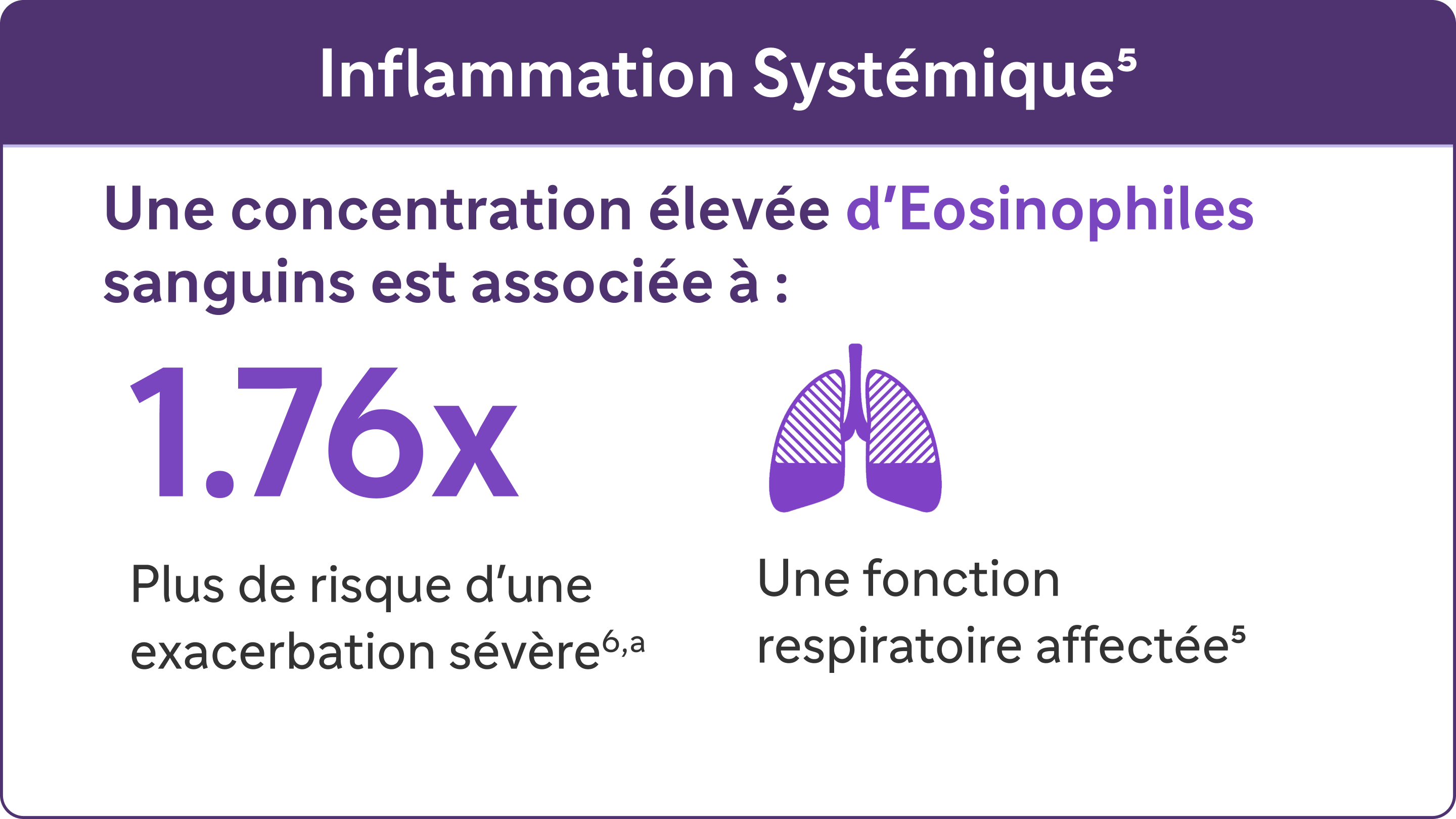

La BPCO est une maladie inflammatoire qui se manifeste au niveau systémique et local. Dans l’inflammation de type 2, on observe les caractéristiques suivantes5, 8

L'inflammation chronique provoque des changements structurels, notamment un rétrécissement des voies respiratoires et une diminution de l'élasticité des poumons5.

Des études ont mis en évidence l’association entre l’inflammation de type 2 et l’ augmentation du risque d’exacerbations et d’altération de la fonction respiratoire dans la BPCO5,6,7

Écoutez le professeur Nicola Hanania : « Nous ne considérons plus cette maladie comme une maladie universelle »

1:36 minutes

Nicola Hanania est professeur de médecine, chef de section des soins intensifs pulmonaires et de la médecine du sommeil à l'hôpital Ben Taub de Houston, au Texas, et directeur du centre de recherche clinique sur les voies respiratoires, ACRC, au Bear College of Medicine.

.webp)

Écouter l'épisode complet du podcast sur le site de l'EMJ

Sponsorisé par Sanofi et Regeneron, en partenariat avec l'EMJ.

I think our approach to this all disease has changed, knowing that it has multiple what we call phenotypes, but also not only that, but we have identified multiple mechanism of the disease, so we no longer look at it as a one-size-fits-all disease. And so therefore it's very important for clinician to do some really digging deep into history to identify these phenotypes, whether it's a frequent exacerbative phenotype, whether it's a chronic bronchitic phenotype, whether it's an emphysema mainly phenotype, but now we use biomarkers like blood eosinophils and maybe more to come, including radiology biomarkers in the future, may help us subdivide this group of patients so that we can do a more personalized approach. And I think it's very exciting time for COPD, so we have moved from this blue-bloater pink puffer type approach to now having multiple, as I mentioned, subtypes or phenotypes, and including the identifying more mechanism so that we have more targeted approach to this disease. And hopefully that will help improve outcomes in the future, obviously. That's the main goal is to move that increased risk of mortality that we have seen in COPD, while we have seen so much achievement with other diseases in COPD. Unfortunately, we haven't moved that envelope a lot, so I think we're hoping with new approaches we may improve outcomes.

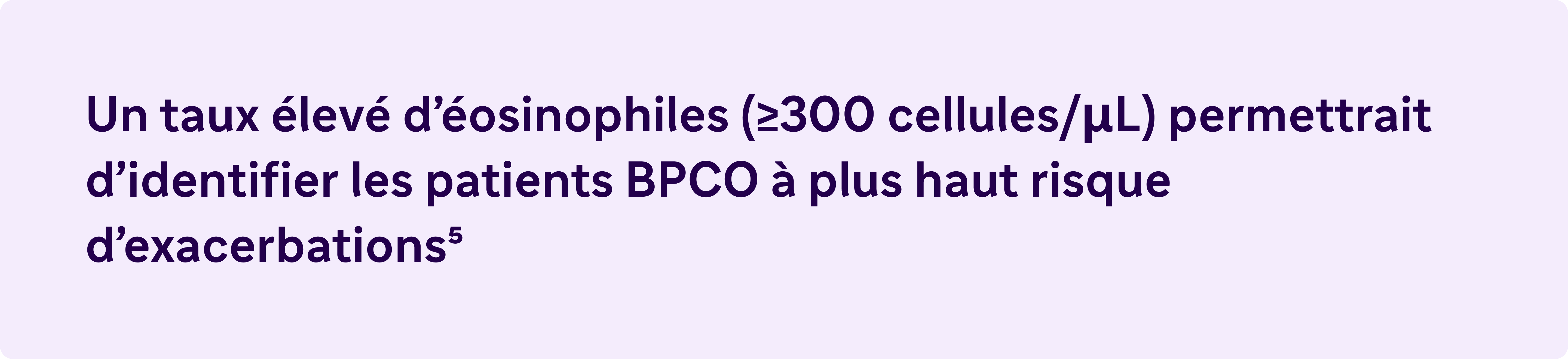

Eosinophiles sanguins élevés (≥ 300 cellules/ μL) – Un biomarqueur de l’inflammation de type 2 dans la BPCO5

Le rapport GOLD 2024 reconnaît une éosinophilie sanguine élevée comme un biomarqueur cliniquement utilisé pour identifier la BPCO avec inflammation de type 2.5

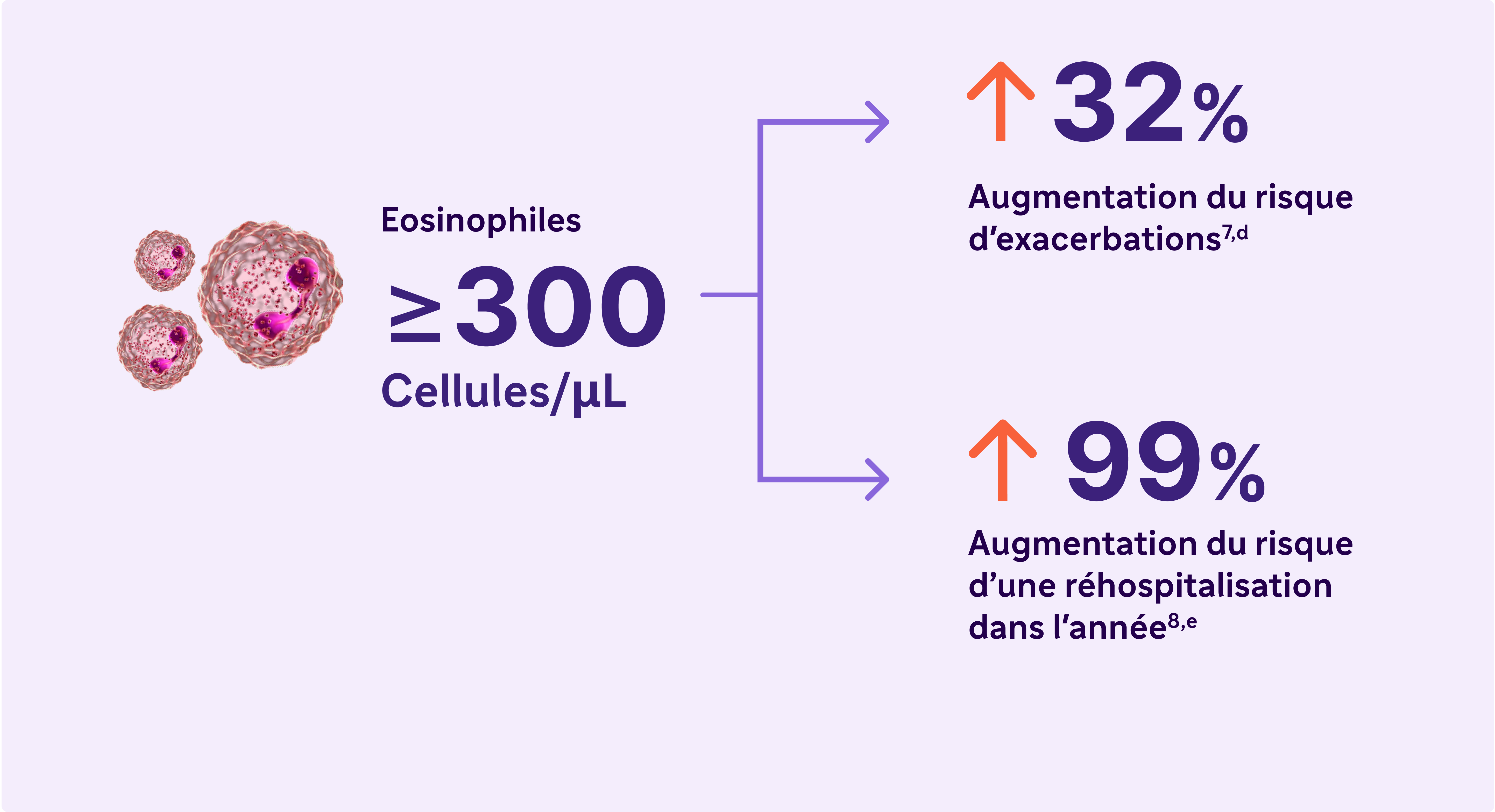

L'inflammation de type 2 dans la BPCO peut impliquer de multiples voies, cytokines et cellules inflammatoires.10,16

.png)

L’inflammation de type 2 dans la BPCO implique les cytokines IL-4, IL-5 et IL-13

.png)

a Une exacerbation sévère était définie comme une hospitalisation due à une BPCO. Les exacerbations devaient être espacées d'au moins 4 semaines pour être considérées comme des exacerbations distinctes.7-8

b Reproduit avec l’autorisation de l’American Thoracic Society. Fritzsching B et coll. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2015;191(8):902-913

c Coloration PAS au bleu Alcian du mucus dans les cellules épithéliales des voies respiratoires.

d Résultats d’une étude observationnelle de 1553 patients atteints de BPCO de grade 2 à 4 selon la spirométrie GOLD (rapport VEMS postbronchodilatateur/CVF < 0,7, avec VEMS > 80 % prédit)7

e Résultats d’une étude observationnelle d’un an portant sur 479 patients atteints de BPCO, dont 103 avaient des taux sanguins d’éosinophiles supérieurs ou égaux à 300 cellules/μL et/ou supérieurs ou égaux à 3% du nombre total de globules blancs.8

Références

- Antus, B. and I. Barta, Blood Eosinophils and Exhaled Nitric Oxide: Surrogate Biomarkers of Airway Eosinophilia in Stable COPD and Exacerbation. Biomedicines, 2022. 10(9).

- David, B., et al., Eosinophilic inflammation in COPD: from an inflammatory marker to a treatable trait. Thorax, 2021. 76(2): p. 188-195.

- Sivapalan, P. and J.U. Jensen, Biomarkers in Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease: Emerging Roles of Eosinophils and Procalcitonin. J Innate Immun, 2022

- Tashkin, D.P. and M.E. Wechsler, Role of eosinophils in airway inflammation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis, 2018. 13: p. 335-349

- Global Strategy for the Diagnosis, Management, and Prevention of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease - Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) - 2024 report.

- Vedel-Krogh S, Nielsen SF, Lange P, Vestbo J, Nordestgaard BG. Blood Eosinophils and Exacerbations in Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. The Copenhagen General Population Study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2016 May 1;193(9):965-74

- Yun JH, Lamb A, Chase R et al ; COPDGene and ECLIPSE Investigators. Blood eosinophil count thresholds and exacerbations in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2018 Jun;141(6):2037-2047.e10. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2018.04.010

- Sethi S. et al. Inflammation in COPD: implications for management. Am J Med. 2012 Dec;125(12):1162-70. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2012.06.024

-

- Bélanger M, Couillard S, et al. Eosinophil counts in first COPD hospitalizations: a comparison of health service utilization. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2018 Oct 1;13:3045-3054.

- Yousuf A, Ibrahim W, Greening NJ, Brightling CE. T2 biologics for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2019;7(5):1406-1416.

- Barnes PJ. Inflammatory endotypes in COPD. Allergy. 2019;74(7):1249-1256.

- Oishi K, Matsunaga K, Shirai T, Hirai K, Gon Y. Role of type 2 inflammatory biomarkers in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J Clin Med. 2020;9(8):2670. doi:10.3390/jcm9082670

- Gabryelska A, Kuna P, Antczak A, Białasiewicz P, Panek M. IL-33 mediated inflammation in chronic respiratory diseases—understanding the role of the member of IL-1 superfamily. Front Immunol. 2019;10:692. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2019.00692

- Allinne J, Scott G, Lim WK, et al. IL-33 blockade affects mediators of persistence and exacerbation in a model of chronic airway inflammation. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2019;144(6):1624-1637.e10.

- Calderon AA, Dimond C, Choy DF, et al. Targeting interleukin-33 and thymic stromal lymphopoietin pathways for novel pulmonary therapeutics in asthma and COPD. Eur Respir Rev. 2023;32(167):220144.

- Gandhi NA, Bennett BL, Graham NMH, Pirozzi G, Stahl N, Yancopoulos D. Targeting key proximal drivers of type 2 inflammation in disease. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2016;15(1):35-50.

- Rosenberg HF, Phipps S, Foster PS. Eosinophil trafficking in allergy and asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2007;119(6):1303-1310.

- Doyle AD, Mukherjee M, LeSuer WE, et al. Eosinophil-derived IL-13 promotes emphysema. Eur Respir J. 2019;53(5):1801291. doi:10.1183/13993003.01291-2018

- Barnes PJ. Inflammatory mechanisms in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2016;138(1):16-27.

- Defrance T, Carayon P, Billian G, et al. Interleukin 13 is a B cell stimulating factor. J Exp Med. 1994;179(1):135-143.

- Yanagihara Y, Ikizawa K, Kajiwara K, Koshio T, Basaki Y, Akiyama K. Functional significance of IL-4 receptor on B cells in IL-4-induced human IgE production. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1995;96(6 pt 2):1145-1151.

- Gandhi NA, Pirozzi G, Graham NMH. Commonality of the IL-4/IL-13 pathway in atopic diseases. Expert Rev Clin Immunol. 2017;13(5):425-437.

- Kaur D, Hollins F, Woodman L, et al. Mast cells express IL-13Rα1: IL-13 promotes human lung mast cell proliferation and FcεRI expression. Allergy. 2006;61(9):1047-1053.

- Saatian B, Rezaee F, Desando S, et al. Interleukin-4 and interleukin-13 cause barrier dysfunction in human epithelial cells. Tissue Barriers. 2013;1(2)

- Zheng T, Zhu Z, Wang Z, et al. Inducible targeting of IL-13 to the adult lung causes matrix metalloproteinase- and cathepsin-dependent emphysema. J Clin Invest. 2000;106(9):1081-1093.

- Brightling CE, Saha S, Hollins F. Interleukin-13: prospects for new treatment. Clin Exp Allergy. 2010;40(1):42-49.

- Garudadri S, Woodruff PG. Targeting chronic obstructive pulmonary disease phenotypes, endotypes, and biomarkers. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2018:15(suppl 4):S234-S238.

- Alevy YG, Patel AC, Romero AG, et al. IL-13-induced airway mucus production is attenuated by MAPK13 inhibition. J Clin Invest. 2012;122(12):4555-4568.

- Singanayagam A, Footitt J, Marczynski M, et al. Airway mucins promote immunopathology in virus-exacerbated chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J Clin Invest. 2022;132(8)-e12901. doi:10.1172/JCI120901.

- Zhu Z, Homer RJ, Wang Z, et al. Pulmonary expression of interleukin-13 causes inflammation, mucus hypersecretion, subepithelial fibrosis, physiologic abnormalities, and eotaxin production. J Clin Invest. 1999;103(6):779-788.

240801151663EE 08/2024