- Artículo

- Fuente: Campus Sanofi

- 3 dic 2024

El impacto de las exacerbaciones en la EPOC

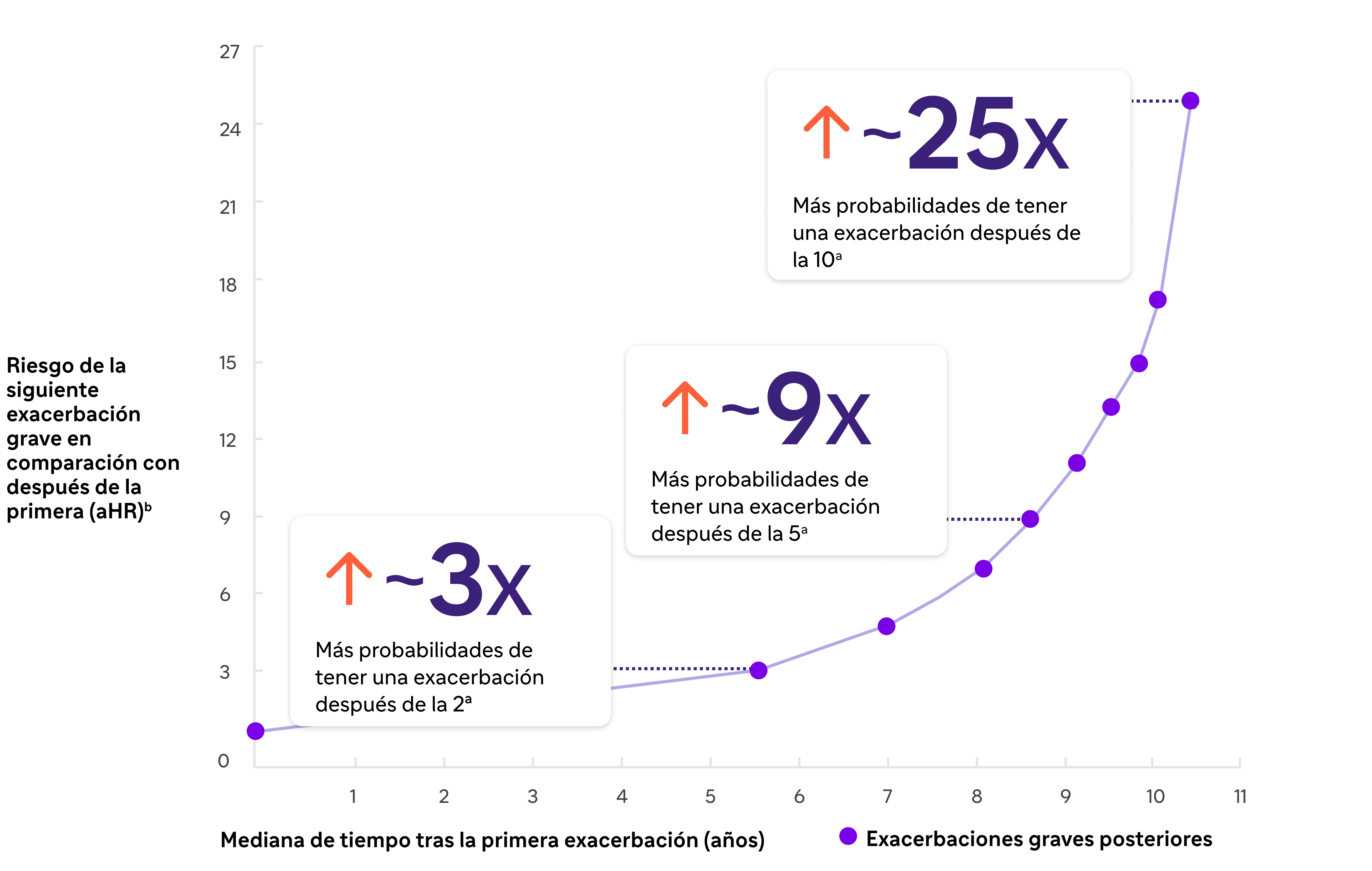

Se ha demostrado que el riesgo de exacerbación de la EPOC se acelera después de cada exacerbación.2,a

El riesgo de exacerbación se acelera después de cada exacerbación1

*Las exacerbaciones graves se definieron como aquellas que dieron lugar a una hospitalización con un diagnóstico primario de EPOC2.

A pesar de la triple terapia inhalada (LABA+LAMA+CI)c, el estándar actual de tratamiento, muchos pacientes siguen siendo sintomáticos, definidos por la persistencia de los síntomas y las exacerbaciones.

Escuche a la profesora Nicola Hanania: «La prevención de las exacerbaciones es el objetivo clave»

2:07 minutos

Nicola Hanania es catedrática de Medicina, jefa de sección de Cuidados Críticos Pulmonares y Medicina del Sueño en el Hospital Ben Taub de Houston (Texas) y director del Centro de Investigación Clínica de las Vías Respiratorias (ACRC) de la Facultad de Medicina de Baylor.

Escuche el episodio completo del podcast en el sitio web de EMJ (European medical Journal - Noviembre de 2024)

Patrocinado por Sanofi y Regeneron, en colaboración con EMJ.

Por desgracia, la EPOC es una enfermedad crónica, como su propio nombre indica. Es una enfermedad progresiva. Aunque no podemos curarla, podemos controlarla, podemos tratarla. Por desgracia, hay varios acontecimientos en el curso de la enfermedad que la empeoran, no sólo para el paciente sino para el sistema sanitario: aumenta el riesgo de hospitalización, la mortalidad... Y uno de ellos son las exacerbaciones. Yo las llamo «ataques pulmonares». Más o menos lo que ocurre con las exacerbaciones es que estos pacientes que tienen síntomas diarios empiezan a tener más síntomas, pueden tener más tos, aumento de la producción de esputo, a veces estas exacerbaciones están provocadas por infecciones -en realidad, la mayoría de las veces- y acaban necesitando más y más tratamientos, incluidos antibióticos, esteroides. Y a veces, por desgracia, pueden acabar obligando al paciente a acudir a urgencias o a ser hospitalizado. Desgraciadamente, las exacerbaciones no son sólo el hecho de que se produzcan y podamos tratarlas, sino que cada vez que el paciente sufre una exacerbación su función pulmonar disminuye. De hecho, ahora contamos con buenos datos que demuestran que las exacerbaciones repetidas pueden contribuir a aumentar el riesgo de empeoramiento de las exacerbaciones futuras, pero también al deterioro de la función pulmonar a largo plazo, sin lograr una recuperación total de la misma. Por lo tanto, cada vez que los pacientes experimentan una exacerbación, esto afecta tanto su función pulmonar como su calidad de vida. Definitivamente hay buenos datos que demuestran que las exacerbaciones repetidas se han relacionado con un aumento de la mortalidad y así sucesivamente. Por eso, uno de los principales objetivos en el tratamiento de esta enfermedad es intentar evitar que se produzcan estos ataques pulmonares. La prevención de las exacerbaciones es el objetivo clave en el manejo de esta enfermedad. Naturalmente, las exacerbaciones suelen ser más frecuentes en los pacientes con una enfermedad más grave. Aunque en algunas situaciones también pueden presentarse en formas moderadas de exacerbación.

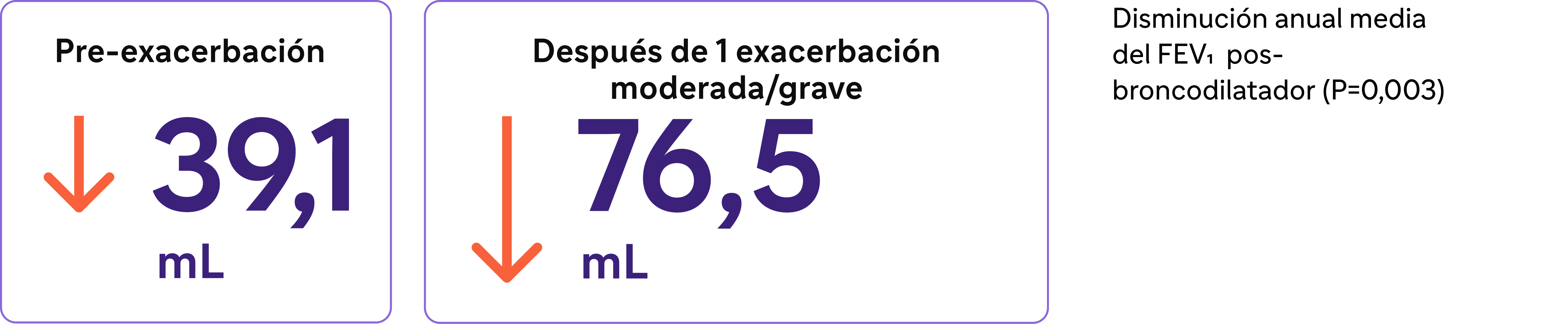

Las exacerbaciones de la EPOC pueden acelerar el deterioro de la función pulmonar3,e

- La pérdida de función pulmonar casi se duplica3

- Puede producirse un deterioro irreversible de la función pulmonar tras una sola exacerbación de la EPOC3

aBasado en datos de una gran cohorte poblacional de 73.106 pacientes canadienses (edad media 75 años) que fueron hospitalizados por primera vez debido a una exacerbación grave de EPOC (1990-2005, seguidos hasta la muerte o hasta el 31 de marzo de 2007).2

bAjustado por edad, sexo, tiempo de calendario y Chronic Disease Score modificado.2

cO doble terapia inhalada si los CSI están contraindicados.15

dEnsayo aleatorizado, doble ciego, de fase 3, de 52 semanas de duración, que evaluó la eficacia y la seguridad del tratamiento triple con furoato de fluticasona/umeclidinio/vilanterol frente a furoato de fluticasona/vilanterol o umeclidinio/vilanterol en pacientes de edad ≥40 años con EPOC sintomática y antecedentes de exacerbaciones.2

Disminución del FEV1 tras una única exacerbación de moderada a grave. Basado en un análisis retrospectivo de datos de 586 pacientes con EPOC de moderada a grave.5

aHR: razón de riesgo ajustada; EPOC: enfermedad pulmonar obstructiva crónica; FEV1: volumen espiratorio forzado en 1 segundo; CdV: calidad de vida ; CI: corticoides Inhalados.

Referencias

1. Halpin DMG, Dransfield MT, Han MK, et al. The effect of exacerbation history on outcomes in the IMPACT trial. Eur Respir J. 2020;55:1901921. doi:10.1183/13993003.01921-2019

2. Suissa S, Dell’Anniello S, Ernst P. Long-term natural history of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: severe exacerbations and mortality. Thorax. 2012;67(11):957-963.

3. Halpin DMG, Decramer M, Celli BR, Mueller A, Metzdorf N, Tashkin DP. Effect of a single exacerbation on decline in lung function in COPD. Respir Med. 2017;128:85-91.

4. Cosio Piqueras MG, Cosio MG. Disease of the airways in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Eur Respir J. 2001;18(suppl 34):41s-49s.

5. Tajti G, Gesztelyi R, Pak K, et al. Positive correlation of airway resistance and serum asymmetric dimethylarginine level in COPD patients with systemic markers of low-grade inflammation. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2017;12:873-884.

6. Higham A, Quinn AM, Cançado JED, Singh D. The pathology of small airways disease in COPD: historical aspects and future directions. Respir Res. 2019;20(1):49. doi:10.1186/s12931-019-1017-y

7. O’Donnell DE, Parker CM. COPD exacerbations. 3: Pathophysiology. Thorax. 200661(4):354-361.

8. Calverley PMA. Respiratory failure in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Eur Respir J. 2003;22:26s-30s.

9. Roussos C, Koutsoukou A. Respiratory failure. Eur Respir J. 2003;22(suppl 47):3s-14s.

10. Aghapour M, Raee P, Moghaddam SJ, Hiemstra PS, Heijink IH. Airway epithelial barrier dysfunction in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: role of cigarette smoke exposure. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2018;58(2):157-169.

11. Brightling CE, Saha S, Hollins F. Interleukin-13: prospects for new treatment. Clin Exp Allergy. 2010;40(1):42-49.

12. Barberà JA, Peinado VI, Santos S. Pulmonary hypertension in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Eur Respir J. 2003;21(5):892-905.

13. Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease. Global strategy for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (2024 report). Accessed [February 9, 2024]. https://goldcopd.org/2024-gold-report-2/

14. Jones PW. St George’s Respiratory Questionnaire: MCID. COPD. 2005 Mar;2(1):75-79.

15. Jones P. St George’s Respiratory Questionnaire Manual. [Version 2.4, March 2022]. Accessed [February 9, 2024]. https://www.sgul.ac.uk/research/research-operations/research-administration/st-georges-respiratory-questionnaire/docs/SGRQ-Manual-March-2022.pdf

16. Evidera website. EXACT and E-RS:COPD content. Accessed [February 9, 2024]. https://www.evidera.com/what-we-do/patient-centered-research/coa-instrument-management-services/exact-program/ exact-content/

17. Leidy NK, Bushnell DM, Thach C, Hache C, Gutzwiller FS. Interpreting Evaluating Respiratory Symptoms in COPD diary scores in clinical trials: terminology, methods, and recommendations. Chronic Obstr Pulm Dis. 2022;9(4):576-590.

18. Oshagbemi OA, Franssen FME, van Kraaij S, et al. Blood eosinophil counts, withdrawal of inhaled corticosteroids and risk of COPD exacerbations and mortality in the clinical practice research datalink (CPRD). COPD. 2019;16(2):152-159.

19. Casanova C, Celli BR, de-Torres JP, et al. Prevalence of persistent blood eosinophilia: relation to outcomes in patients with COPD. Eur Respir J. 2017;50:1701162. doi:10.1183/13993003.01162-2017

20. Singh D, Kolsum U, Brightling CE, Locantore N, Agusti A, Tal-Singer R; ECLIPSE investigators. Eosinophilic inflammation in COPD: prevalence and clinical characteristics. Eur Respir J. 2014;44(6):1697-1700.

21. Bafadhel M, McKenna S, Terry S, et al. Acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: identification of biologic clusters and their biomarkers. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;184(6):662-671.

22. Oshagbemi OA, Burden AM, Braeken DCW, et al. Stability of blood eosinophils in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and in control subjects, and the impact of sex, age, smoking, and baseline counts. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2017;195(10):1402-1404.

23. Yun JH, Lamb A, Chase R, et al; COPDGene and ECLIPSE Investigators. Blood eosinophil count thresholds and exacerbations in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2018;141(6):2037-2047.e10. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2018.04.010

24. Bélanger M, Couillard S, Courteau J, et al. Eosinophil counts in first COPD hospitalizations: a comparison of health service utilization. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2018;13:3045-3054.

25. Fritzsching B, Zhou-Suckow Z, Trojanek JB, et al. Hypoxic epithelial necrosis triggers neutrophilic inflammation via IL-1 receptor signaling in cystic fibrosis lung disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2015;191(8):902-913.

26. Vedel-Krogh S, Nielsen SF, Lange P, Vestbo J, Nordestgaard BG. Blood eosinophils and exacerbations in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. The Copenhagen General Population Study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2016;193(9):965-974.

27. George L, Taylor AR, Esteve- Codina A, et al; U-BIOPRED and the EvA study teams. Blood eosinophil count and airway epithelial transcriptome relationships in COPD versus asthma. Allergy. 2020;75(2):370-380.

28. Yousuf A, Ibrahim W, Greening NJ, Brightling CE. T2 biologics for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2019;7(5):1406-1416.

29. Barnes PJ. Inflammatory endotypes in COPD. Allergy. 2019;74(7):1249-1256.

30. Oishi K, Matsunaga K, Shirai T, Hirai K, Gon Y. Role of type 2 inflammatory biomarkers in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J Clin Med. 2020;9(8):2670. doi:10.3390/jcm9082670

31. Gabryelska A, Kuna P, Antczak A, Białasiewicz P, Panek M. IL-33 mediated inflammation in chronic respiratory diseases—understanding the role of the member of IL-1 superfamily. Front Immunol. 2019;10:692. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2019.00692

32. Allinne J, Scott G, Lim WK, et al. IL-33 blockade affects mediators of persistence and exacerbation in a model of chronic airway inflammation. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2019;144(6):1624-1637.e10.

33. Calderon AA, Dimond C, Choy DF, et al. Targeting interleukin-33 and thymic stromal lymphopoietin pathways for novel pulmonary therapeutics in asthma and COPD. Eur Respir Rev. 2023;32(167):220144. doi:10.1183/16000617.0144-2022

34. Gandhi NA, Bennett BL, Graham NMH, Pirozzi G, Stahl N, Yancopoulos D. Targeting key proximal drivers of type 2 inflammation in disease. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2016;15(1):35-50.

35. Rosenberg HF, Phipps S, Foster PS. Eosinophil trafficking in allergy and asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2007;119(6):1303-1310.

36. Doyle AD, Mukherjee M, LeSuer WE, et al. Eosinophil-derived IL-13 promotes emphysema. Eur Respir J. 2019;53(5):1801291. doi:10.1183/13993003.01291-2018

37. Barnes PJ. Inflammatory mechanisms in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2016;138(1):16-27.

38. Defrance T, Carayon P, Billian G, et al. Interleukin 13 is a B cell stimulating factor. J Exp Med. 1994;179(1):135-143.

39. Yanagihara Y, Ikizawa K, Kajiwara K, Koshio T, Basaki Y, Akiyama K. Functional significance of IL-4 receptor on B cells in IL-4– induced human IgE production. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1995;96(6 pt 2):1145-1151.

40. Gandhi NA, Pirozzi G, Graham NMH. Commonality of the IL-4/IL-13 pathway in atopic diseases. Expert Rev Clin Immunol. 2017;13(5):425-437.

41. Kaur D, Hollins F, Woodman L, et al. Mast cells express IL-13Rα1: IL-13 promotes human lung mast cell proliferation and FcεRI expression. Allergy. 2006;61(9):1047-1053.

42. Saatian B, Rezaee F, Desando S, et al. Interleukin-4 and interleukin-13 cause barrier dysfunction in human epithelial cells. Tissue Barriers. 2013;1(2):e24333. doi:10.4161/tisb.24333

43. Zheng T, Zhu Z, Wang Z, et al. Inducible targeting of IL-13 to the adult lung causes matrix metalloproteinase– and cathepsin-dependent emphysema. J Clin Invest. 2000;106(9):1081-1093.

44. Garudadri S, Woodruff PG. Targeting chronic obstructive pulmonary disease phenotypes, endotypes, and biomarkers. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2018;15(suppl 4):S234-S238.

45. Alevy YG, Patel AC, Romero AG, et al. IL-13–induced airway mucus production is attenuated by MAPK13 inhibition. J Clin Invest. 2012;122(12):4555-4568.

46. Singanayagam A, Footitt J, Marczynski M, et al. Airway mucins promote immunopathology in virus-exacerbated chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J Clin Invest. 2022;132(8):e12901. doi:10.1172/JCI120901

47. Zhu Z, Homer RJ, Wang Z, et al. Pulmonary expression of interleukin-13 causes inflammation, mucus hypersecretion, subepithelial fibrosis, physiologic abnormalities, and eotaxin production. J Clin Invest. 1999;103(6):779-788.

48. Cooper PR, Poll CT, Barnes PJ, Sturton RG. Involvement of IL-13 in tobacco smoke-induced changes in the structure and function of rat intrapulmonary airways. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2010;43(2):220-226.

49. Arora S, Dev K, Agarwal B, Das P, Syed MA. Macrophages: their role, activation, and polarization in pulmonary diseases. Immunobiology. 2018;223(4-5):383-396.

50. He S, Xie L, Lu J, Sun S. Characteristics and potential role of M2 macrophages in COPD. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2017;12:3029-3039.

51. Wang X, Xu C, Ji J, et al. IL-4/IL-13 upregulates Sonic hedgehog expression to induce allergic airway epithelial remodeling. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2020;318(5):L888-L899.

52. Linden D, Guo-Parke H, Coyle PV, et al. Respiratory viral infection: a potential “missing link” in the pathogenesis of COPD. Eur Respir Rev. 2019;28(151):180063. doi:10.1183/16000617.0063-2018

53. Wang Z, Bafadhel M, Haldar K, et al. Lung microbiome dynamics in COPD exacerbations. Eur Respir J. 2016;47(4):1082-1092.

MAT-ES-2402663 -V1- Noviembre 2024